Narrative Development in Monolingual Spanish-Speaking Preschool Children

Anny Castilla-Earls

Department of Communication Disorders and Sciences, SUNY Fredonia

Douglas Petersen

Department of Communication Disorders, University of Wyoming

Trina Spencer

Institute for Human Development, Northern Arizona University

Krista Hammer

Rochester Hearing and Speech Center, Rochester, New York

Research Findings: The purpose of this study was to describe differences in the narratives produced by 3-, 4-, and 5- year old Spanish-speaking (SS) children. Narrative productions of 104 typically developing children were collected using a story-retelling task and coded using the Index of Narrative Complexity. The results of this study indicate that 3-year-old SS children produced stories containing characters and actions. Four-year-old SS children’s stories were characterized by the use of characters, actions, and internal responses. Five-year-old SS children retold stories containing characters, settings, initiating events, actions, internal responses, formulaic markers, temporal markers, and knowledge of dialogue. Practice: Developmental information to assist educators working with SS children.

Most children with early expressive language difficulties appear to achieve age-appropriate language skills by the time they are 3 years old (Ellis Weismer, 2007; Ellis & Thal, 2008; Paul, 1991, 1996; Paul, Murray, Clancy, & Andrews, 1997). However, three notable studies have indicated that late talkers tend to show language difficulties in elementary school, even though at the end of preschool these children may appear to have caught up with their typically developing peers (Paul et al., 1997; Rescorla, 2002; Rice, Taylor, & Zubrick, 2008). Apparent recovery at the end of preschool may be an artifact of inadequate assessment. Language difficulties are more apparent in some dimensions of language than others. Vocabulary is a common measure of language ability for preschool children, yet research has indicated that more complex measures of language skills, including syntax and working memory, can reveal persistent language difficulties (Paul et al., 1997; Rescorla, 2002). A body of research indicates that when a child’s language abilities are sufficiently taxed, existing language difficulties will be evident (Abild-Lane, 1996; Lahey, 1990; Paul, 2000; Paul, Hernandez, Taylor, & Johnson, 1996; Paul & Smith, 1993; Rescorla, 2002). In addition, research has indicated that 5-year-old children who have a language impairment are likely to continue

to have clinically significant problems throughout their school years (e.g., Bishop & Edmundson, 1987; Tomblin, Zhang, Buckwalter, & O’Brien, 2003). Given the possibility then that language

difficulties may be hidden, and given the importance of detecting language difficulties early in order to address language problems, it is paramount to test for age-appropriate language abilities using an approach that reveals language impairment at an early age. Therefore, innovative assessment approaches that distinguish effectively between delayed or different language and language impairment at an early age are critically needed. Among the many possible language assessment approaches, narrative assessment stands out as a distinctive and viable option.

Given the growing cultural and linguistic diversity across public schools in the United States, it is becoming increasingly important to have appropriate measures to evaluate culturally and linguistically diverse children. The U.S. Census Bureau (2011) reported that approximately 35 million people speak Spanish at home in the United States. Hispanics are currently the fastest growing population in the United States, and projections indicate that this ethnic group will continue to grow in the years to come. Narrative assessment is a highly recommended practice for the evaluation of language skills in Spanish-speaking (SS) children (Fiestas & Peña, 2004; Rojas & Iglesias, 2009). The purpose of the current study is to describe the narrative skills of a group of young monolingual SS children to provide preliminary developmental benchmarks that could potentially be used as a tool for the identification of language disorders in this population.

NARRATIVE ASSESSMENT

The production of narratives requires the ability to create an appropriate story structure and to use complex-literate language to narrate the story (Klecan-Aker & Hedrick, 1985; Paul & Smith, 1993; Scott, 1988), thus taxing a child’s language system. Narrative assessment facilitates the analysis of language not only within utterances (e.g., morphosyntax) but also across utterances (e.g.,

macrostructure). There is evidence that the assessment of narratives, especially the analysis of language produced across utterances, is a useful clinical tool for identifying children with language impairment (Botting, 2002; Cain, 2003; John, Lui, & Tannock, 2003; Liles, 1987; Merritt & Liles, 1987; Muñoz, Gillam, Peña, & Gulley-Faehnle, 2003; Petersen, Gillam, & Gillam, 2008; Scott & Windsor, 2000; Ukrainetz & Gillam, 2009; Wagner, Nettelbladt, Sahlén, & Nilholm, 2000). For example, Fey, Catts, Proctor-Williams, Tomblin, and Zhang (2004) found that the narrative quality of stories (characters, setting, conclusion, plot complexity, and language sophistication) produced by English-speaking children with language impairments was significantly lower than that of children with typical development. Similar results have been found for SS children (Coloma, 2014) and for dual language learners (Cleave, Girolametto, Chen, & Johnson, 2010).

In addition to its diagnostic utility, narrative proficiency is an important predictor of academic success (Bishop & Edmundson, 1987; Fazio, Naremore, & Connell, 1996; O’Neill, Pearce, & Pick, 2004; Speece, Roth, Cooper, & de la Paz, 1999). There is a positive correlation between oral language and reading ability (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zhang, 2002; Dickinson & McCabe, 2001; Griffin, Hemphill, Camp, & Wolf, 2004). As a result, narrative language provides insight into the complex language needed for literacy.

The assessment of oral language using narratives, therefore, plays an important role in the detection of language impairments and language-related literacy problems that might lead to academic difficulties. Narrative assessment of language skills in children often includes a comparison against developmental benchmarks to determine whether the language skills of a child are within or below typical expectations in comparison to other children of the same age. The more sensitive a measure is to subtle differences in children’s language productions, the more accurate researchers and clinicians can be at mapping typical development as well as determining what is sufficiently deviant from the norm to warrant concern.

Narrative assessment includes the analysis of microstructure and macrostructure elements. The analysis of narrative microstructure entails a focus on language features such as mean length of utterance, number of different words, total number of words, number of C-units, grammaticality, and subordination. In addition, narrative microstructure often includes an analysis of literate language features, including coordinating conjunctions, elaborated noun phrases, causal and temporal subordinating conjunctions, adverbs, and verbs that reflect mental and linguistic states (Greenhalgh & Strong, 2001; Nippold, 1998; Nippold, & Taylor, 1995; Nippold, WardLonergan, & Fanning, 2005; Strong & Shaver, 1991; Westby, 1999).

Narratives tend to follow a predictable pattern of organization composed of elements often referred to as narrative macrostructure. Out of many different organizational schemas proposed

by various researchers (Applebee, 1978; Labov, 1972; Peterson & McCabe, 1983; Stein & Glenn, 1979), the Stein and Glenn (1979) concept of story grammar is one of the most widely

used in research and clinical practice. The macrostructure elements include the setting, the initiating event (typically a problem), the internal response (feelings), a plan or attempt to solve the

problem, the consequence, and the resolution.

The analysis of narrative macrostructure has historically entailed the use of a dichotomous scoring procedure that acknowledges the presence or absence of categorical story features.

Recent English narrative assessment procedures that utilize a graded, multipoint scoring system are sensitive to variations in story structure (Gillam & Justice, 2010; Heilmann, Miller, Nockerts,

& Dunaway, 2010; Petersen et al., 2008; Petersen & Spencer, 2012). These measures are generally built on the foundation of a theory of narrative schemata. At their core are commonalities that can be generalized across measures and across cultures and languages (Berman & Slobin, 1994). For example, the Index of Narrative Complexity (INC; Petersen et al., 2008) and the Narrative Scoring Scheme (Heilmann et al., 2010), among others, score narrative macrostructure features that relate to the traditional Stein and Glenn (1979) story grammar model.

There have also been recent developments in the analysis of narrative microstructure, yielding more sensitive measures. For example, the Index of Narrative Micro-Structure (Justice et al., 2006) and the Narrative Assessment Protocol (Justice, Bowles, Pence, & Gosse, 2010) are specifically designed to measure narrative microstructure. Fortunately, measures such as the INC (Petersen et al., 2008) include both microstructure and macrostructure elements.

NARRATIVE DEVELOPMENT WITHIN AND BETWEEN LANGUAGES

To use assessment results to classify children as having age-appropriate skills or as lacking these skills, an understanding of typical language production at specific age ranges is necessary. Narrative developmental research, although quite limited, indicates that differences in both macrostructure and microstructure are evident in children who are 3, 4, and 5 years of age. For example, minimal episodic structures in English typically emerge around 4 years of age for English-speaking children and are more evident in a typical 5-year-old child’s narrative productions (Curenton & Justice, 2004; McCabe & Rollins, 1994; Peterson & McCabe, 1983).

In a seminal study on cross-linguistic narrative developmental patterns, Berman and Slobin (1994) examined the development of narrative abilities in preschoolers, school-age children, and adults who spoke English, German, Spanish, Hebrew, or Turkish. They elicited narratives using a wordless picture book (Frog story). Their results indicated that younger children used less complex language and fewer macrostructure elements. Berman and Slobin found that only 3% of 3-year-olds produced an initiating event, attempt, and consequence, whereas 14% of 4-year-olds and 34% of 5-year-olds were able to produce a complete episode. Their analysis of cross-linguistic differences revealed story grammar consistency across languages for children who were 5 years old or older. This consistency across languages was not evident in the 3- and 4-year-old participants. Berman and Slobin reported that 83% of the English-speaking 4-year olds included an initiating event, yet only 25% of the Hebrew-Speaking children did so. They also noted that 50% of the SS 3-year-olds included an initiating event, yet only 8% of Hebrew speaking and Turkish-speaking children included that element in their stories. These findings indicate that there are likely important developmental differences in narrative production between 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds both within and across languages.

NARRATIVE DEVELOPMENT FOR SS CHILDREN

Developmental information available for young SS children’s narrative production is particularly sparse. A comprehensive review of the literature yielded only two studies that provided sufficient information on the narrative production of SS preschool children. Gutierrez-Clellen and Iglesias (1992) analyzed the narratives of 46 SS children who were asked to retell a narrative from a short silent film. Sixteen typically developing SS children ages 4;0 to 4;11 were included in the study. Results indicated that nearly 75% of the 4-year-olds in this study included actions in their stories but rarely specified why those actions were taking place. These children seldom included internal responses. For microstructure, the 4-year-olds consistently included one causal statement, but causality was rarely if ever included two or more times. Furthermore, verb or noun modifiers were often omitted.

Similarly, Fiestas and Peña (2004) analyzed the macrostructure and microstructure of the narratives of 12 typically developing bilingual (English/Spanish) children ranging in age from 4:0 to 6;11. The children were asked to produce a narrative from a wordless picture book and from a single picture in English and Spanish. Although results were not disaggregated by age, it was evident in the data that the stories produced in Spanish by these children included a description of the characters and the setting and included a purposeful action to accomplish a goal. The children on average did not include all of the elements necessary to produce a minimally complete episode (initiating event, attempt, and consequence). Their Spanish stories tended to include the initiating event and attempt more often than the consequence.

These studies indicate that young typically developing SS children often include information about characters, settings, and goal-oriented actions in their Spanish stories. They rarely produce narratives with complete episodes, often omitting the consequence of actions, and internal responses are typically not included. Microstructure information is quite limited. Currently, it appears that preschool SS children rarely use adjectives and adverbs, but a causal relationship between two events is often expressed. More research is needed to confirm and expand these developmental findings.

Fiestas and Peña (2004) and Rojas and Iglesias (2009) highly recommended the use of narrative analysis for the assessment of language skills in SS children. However, currently there is a lack of developmental information on the narrative production of young SS children. Normative data reflective of a specific population are likely to apply inferentially to an individual who closely matches that normative sample. If normative information is derived from a highly diverse sample of children, and if those data are not disaggregated to reflect specific subgroups, the likelihood of an individual matching the normative sample is low (see Laing & Kamhi, 2003, for a review). This clearly applies to the collection of Spanish normative data for narrative production. When norms reflect the language of a monolingual population, it is possible to hold language constant across subjects and focus on confounding variables, such as limited exposure to that language. Including children with varying language proficiency in a Spanish narrative norming process would only serve to lower the mean of the normative data and make the study of differences across populations difficult. However, once the developmental expectations are defined in the monolingual population, it can then be determined by comparison to what degree bilingualism has an effect on the standard developmental progression.

There are multiple ways to elicit a narrative, and each elicitation procedure and context may affect the language produced by a child. For example, a number of researchers have noted that story retells and picture cues are most effective in eliciting longer and more complex narratives; however, they have also suggested that these retells structure children’s responses contextually (Fiestas & Peña, 2004; Kaderavek & Sulzby, 2000; Morris-Friehe & Sanger, 1992). Currently, much of the knowledge of narrative language development is derived from narrative elicitations using the wordless picture book Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969). Because this book is wordless, and revolves around themes that are relevant across multiple cultures, we consider that it is effective in establishing Spanish narrative developmental baselines.

The purpose of the current study is to describe the narrative skills of a group of young monolingual SS children retelling a narrative from the wordless picture book Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969) using a sensitive, multipoint instrument that measures both macrostructure and microstructure elements (the INC; Petersen et al., 2008). This study provides preliminary developmental benchmarks that could potentially be used as a tool for the identification of language disorders in both monolingual and bilingual SS children. Although research has not yet reported the differences in Spanish narrative production across preschool ages using a contemporary, multipoint rubric, we hypothesize that monolingual SS children will show differences in both macrostructure and microstructure across ages 3, 4, and 5, with story grammar and language complexity increasing with age. Specifically, this study addresses the following question: To what extent do narrative productions of typically developing 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old monolingual SS children differ across macrostructure and microstructure features as measured by the INC?

METHOD

Participants

The total pool of participants consisted of a sample of 109 monolingual SS children residing in Cali, Colombia. The language development of these children has been previously described in Castilla (2008) and Castilla-Earls and Eriks-Brophy (2012). We considered this sample to be appropriate and informative for the description of narrative skills in SS children. These children were recruited from day care centers and preschools. There were 36 children in the 3-year-old group (15 boys and 21 girls; M age¼ 36 months, SD¼ 1.8 months), 39 children in the 4-year-old group (16 boys and 23 girls; M age¼ 48 months, SD¼ 1.9 months), and 34 children in the 5-yearold group (20 boys and 14 girls; M age¼ 59 months, SD¼ 1.9 months). Maternal education level was diverse, with mothers reporting their highest level of education as elementary school (n ¼ 2), high school degree (n ¼ 16), technical degree (n ¼ 24), college degree (n¼ 37), and postgraduate degree (n ¼ 11). The remaining 19 mothers chose not to report this information. All children included in this study passed a hearing screening.

To ensure that the results from this study represented typical language development, we excluded children with language disorders using the following criteria. Children were considered to have language disorders if all three of the following conditions were satisfied: (a) a standard score less than 85 on the Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody (Dunn, Lugo,

Padilla, & Dunn, 1997)—this test was the only available language test normed on a comparable monolingual population (children from Mexico and Puerto Rico) and therefore appropriate for this sample; (b) parental concerns about the language and speech development of their children as evidenced by a score greater than 8 on the Parental Report of Speech and Language Problems

(Restrepo, 1998). and (c) a score less than 1.5 SD from the age group mean on an article and clitic pronoun elicitation task (Castilla, 2008). This task was designed to target grammatical structures that have consistently been found to be problematic for SS children with language disorders. Using these criteria, we eliminated five children from our initial pool of participants.

The remaining 104 children were considered to have typical language development.

Measures and Procedures

The first author of this article tested all children individually at their day care center or preschool in a private room. The entire testing session for each child took approximately 45 min and included the administration of the following tasks in order: (a) a hearing screening, (b) the Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody (Dunn et al., 1997), (c) an elicitation task used for classification purposes (Castilla, 2008). and (d) a story-retelling task. The order of administration of the tasks was standardized to guarantee the best possible tester–child rapport during the story-retelling task. The Parental Report of Speech and Language Problems (Restrepo, 1998) was sent home, completed by parents, and returned to the day care or preschool. We controlled for fatigue and inattention by offering the children breaks as needed, but in general children did not show signs of fatigue and completed all testing with minimal effort. The story-retelling task was administered last to guarantee that the examiner and child had established the best possible rapport, thereby ensuring a naturalistic language sample.

To elicit retell-narrative samples, we used the wordless picture book Frog Goes to Dinner (Mayer, 1974) using a researcher-developed Spanish story script (see the Appendix; Castilla, 2008; Castilla-Earls & Eriks-Brophy, 2012). The use of Frog story retells is a successful and well-documented strategy in the study of child language. The story script included all story microstructure and macrostructure grammar elements used in the INC with the exemption of narrator evaluation (Petersen et al., 2008). The examiner read the story in Spanish while the child looked at the pictures in the book. Once the story was finished, the examiner asked the child to retell the story while looking at the pictures. If a child was hesitant to start retelling the story, the examiner used the first page of the book to ask the child to identify the characters and then asked the child again to retell the story. The examiner provided further support by asking questions such as ¿y entonces qué pasó? (“And then what happened?”) and ¿y qué más? (“What else?”) and praised the child’s efforts to encourage participation. Children retold the story only once. All sessions were recorded using a Sony Mini Disk Hi-MD Walkman Digital Music Player with a Sony ECM-719 electret condenser microphone. The first author, a native Spanish speaker, transcribed each recording following conventions outlined in Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts software Research Version 8 (Miller & Chapman, 2003). An independent trained research assistant blind to the purposes of the study coded each story using the INC to avoid investigator bias.

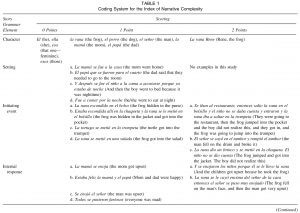

The INC. The INC (Petersen et al., 2008) is a 3-point coding system for scoring narrative productions. It was originally designed as a tool to document progress with language intervention. The INC is a reliable tool for scoring narratives elicited using a variety of techniques (e.g., fictional generations, retells). Petersen et al. (2008) described this assessment tool in great detail and offered examples for all elements in English. We deemed the INC to be an appropriate tool for the purpose of this study because its multipoint approach could potentially identify developmental changes across ages and because it included both microstructure and macrostructure elements. For example, the INC allows an examiner to see differences between a child who makes no mention of a character in his or her story (score of 0), a child who mentions the character without a specific name (score of 1), and a child who includes the character with a proper name in his or her narrative (score of 2). The same multipoint approach is used for macrostructure elements. For example, for the knowledge of dialogue element, a score of 0 corresponds to the absence of dialogue, a score of 1 is assigned to the use of one instance of a character dialogue, and a score of 2 corresponds to at least two characters engaging in a conversation. No modifications were made for scoring Spanish narratives using the INC because the first author, who has extensive experience with Spanish and English narratives, found no obvious differences between the languages. We provide examples of how we used the INC coding system for Spanish in Table 1. The scoring of the story using the INC allowed for the children’s independent interpretation of the story.

Reliability. Interrater reliability was examined for scores for story grammar elements and microstructure features on 21 randomly selected language samples (20%). The first author served as the second rater. Agreement was reached if both coders assigned the same score to each story grammar element or microstructure feature. We calculated reliability using the following formula: agreements divided by agreements plus disagreements multiplied by 100. The total point-by-point interrater reliability for coding of the INC was 91.3%.

RESULTS

To examine the difference in narrative productions of typically developing 3-, 4-, and 5-year old monolingual SS children, we conducted a three-way analysis of variance with the INC total score as the dependent variable and age, gender, and mother’s education as the independent variables. There was a statistically significant main effect for the INC total score among age groups but no statistically significant main effects for gender or mother’s level of education: INC total score, F(2, 95) ¼ 35.812, p < .001; gender, F(1, 96) ¼ 0.212, p ¼ .668; mother’s level of education F(4, 94) ¼ 1.588, p ¼ .516. None of the interactions were significant. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc comparisons for the INC total score revealed that 4-year-olds (M ¼ 8.10, SD ¼ 3.00) scored significantly higher than 3-year-olds (M ¼ 4.44, SD ¼ 1.92), and 5-year-olds (M ¼ 10.13, SD ¼ 2.26) scored significantly higher than 4-year-olds and 3-year-olds on the INC total score.

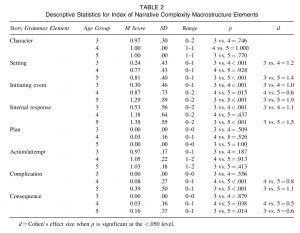

We conducted a multivariate analysis of variance with age group as the independent variable and scores for each individual element of the INC as the dependent variables to examine the differences in specific elements between 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old SS children. Table 2 displays descriptive data and effect sizes (d) for INC macrostructure elements. Several elements of the INC were more likely to be produced by older children than younger children.

As hypothesized, there were statistically significant group differences in INC scores for setting, initiating event, internal response, complication, and consequence: setting, F(2, 101) ¼ 19.650,

p < .001; initiating event, F(2, 101) ¼ 21.839, p < .001; internal response, F(2, 101) ¼ 19.505,

p < .001; complication, F(2, 101) ¼ 13.530, p < .001; consequence, F(2, 101) ¼ 4.749,

p ¼ .011). Some macrostructure elements of the INC were not more prevalent in older

children’s stories. The macrostructure elements of character, plan, and action did not show the same pattern as the other elements: character, F(2, 101) ¼ 0.337, p ¼ .715; plan, F(2, 101) ¼

0.831, p ¼ .439; action, F(2, 101) ¼ 1.656, p < .196. Differences between 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds were not observed for character and action because even the 3-year-olds included them. In contrast, a difference between the age groups was not observed for plan because very few children, including the 5-year-olds, incorporated a plan into their retells. Post hoc comparisons using

Tukey’s HSD test indicated that 4-year-olds produced significantly more settings, initiating events, and internal responses than 3-year-olds. Similarly, 5-year-olds produced significantly more settings, initiating events, internal responses, complications, and consequences than 3-year-olds. Lastly, 5-year-olds produced significantly more initiating events, complications, and consequences than 4-year-olds.

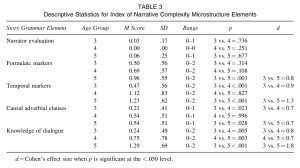

The results for the microstructure elements are displayed in Table 3. In general, older children included more microstructure elements than younger children. There were statistically significant differences in INC scores for formulaic markers, temporal markers, causal adverbial clauses, and knowledge of dialogue: formulaic markers, F(2, 101) ¼ 5.675, p ¼ .005; temporal markers, F(2, 101) ¼ 11.937, p < .001; causal adverbial clauses, F(2, 101) ¼ 4.658, p ¼ .012; knowledge of dialogue, F(2, 101) ¼ 19.841, p < .001. Tukey’s HSD tests indicated that 4-year-olds included more temporal markers, causal adverbial markers, and knowledge of dialogue than 3-year-olds. With respect to microstructure, 5-year-olds produced more knowledge of dialogue than 4-year-olds and more formulaic markers, temporal markers, causal adverbial clauses, and knowledge of dialogue than 3-year-olds.

A difference between age groups was

not detected for narrator evaluation because very few children included that element in their retells. In general, the differences in microstructure elements pointed to a significant distinction between the group of 3-year-olds and the 4- and 5-year-olds combined.

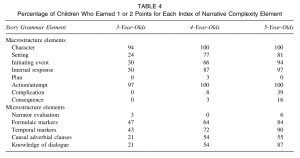

We examined the percentage of typically developing SS children who earned a score of at least 1 for each INC element (see Table 4). It is evident in this data set that older children used more story elements to retell narratives than younger children. Using an arbitrary group acquisition criterion of 80% of children producing a particular story element (score of at least 1), it is possible to describe the narrative production of each age group. Three-year-old SS children produced stories that contained characters and actions. Four-year-old SS children’s stories were characterized by the use of characters, actions, and internal responses. Five-year-old SS children retold stories containing characters, settings, initiating events, actions, internal responses, formulaic markers, temporal markers, and knowledge of dialogue.

DISCUSSION

With the large numbers of SS children entering U.S. schools, the task of distinguishing between typical language development and language differences poses significant challenges to teachers and other professionals. Many promote the assessment of narratives as a valuable assessment procedure because of its relation to general academic performance and because children with language impairments often have difficulty with narration (Fey et al., 2004). Furthermore, narratives collected using language sampling techniques to identify children with language impairment are less susceptible to cultural and linguistic biases than are norm-referenced assessments (Elder, 2012; McCauley & Swisher, 1984). However, the valid interpretation of narrative assessment for SS children requires baseline information regarding typical narrative development.

A developmental pattern across narrative macrostructure and microstructure is expected, especially when children’s oral language skills are burgeoning rapidly between the ages of 3 and 5 years old (Berman & Slobin, 1994). Our findings provide additional evidence that this developmental pattern for both macrostructure and microstructure features is measurable using a multipoint assessment scale such as the INC. Based on total INC scores, mean group differences were statistically significant, indicating that 5-year-olds produced more complex retell narratives than 4-year-olds, who produced more complex retell narratives than 3-yearolds. This developmental pattern is comparable to what has been observed in English-speaking children (Klecan-Aker & Kelty, 1990; Wetsby, 1984).

Narrative Macrostructure

In the more detailed analysis of INC macrostructure elements, we found that 3-year-old monolingual SS children produced retell narratives marked with characters and actions; 4-year-olds most often included characters, internal responses, and actions; and 5-year-olds produced retells with characters, settings, initiating events, internal responses, and actions. From these data, there are several noteworthy findings. For example, the percentage of children including character and action did not increase as a function of age. Almost all of the 3-year-olds included a character (94%) and action (97%), and all of the 4- and 5-year-olds included these features. Even though the inclusion of a 1- or 2-point action was used to calculate percentages, we examined Table 2 to determine whether older children produced actions earning higher points. This was not the case—all three age groups produced mean scores of 1 point (range ¼ 0.97–1.05) for action. These data suggest that characters and actions unrelated to an initiating event were the most salient story structures for children 3 to 5 years of age. Moreover, they emerged early and were stable. At some point, SS children older than 5 years of age likely produce actions that are related to initiating events consistently, which receive 2 points on the INC. The age at which this is developmentally stable will need to be investigated in future research, as will the extent to which these findings hold when other variables, such as type of narrative and stimuli used to elicit the narrative, are manipulated.

Another interesting macrostructure finding is that none of the age groups consistently produced consequences in their retell narratives. In fact, the monolingual children in this study almost never included consequences in their stories, with percentages of 0%, 3%, and 16% for 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds, respectively. This finding may be related to the structure of the model story. For example, in the story used in this study, a frog repeatedly jumps to different places, but rather than resolving the initial problem (initiating event), the frog’s attempts to solve the problem only introduce additional problems. At the very end of the story, after several unresolved attempts, one problem is resolved, and children who retold that content received points for consequence. In other words, the story used in this study included many initiating events and many actions but only one 2-point consequence. Although the nature of the model story offers one possibility for the scarcity of consequences in the SS preschoolers’ retells, Fiestas and Peña (2004) found a related phenomenon that is not likely due to differences in the model story. They collected Spanish and English narratives from bilingual Latino American children (ages 4–6 years) living in Texas and reported that children produced more consequences in their English narratives than they did in Spanish narratives. In the current study, we did not elicit narratives in both languages, but the exclusion of consequences noted in Spanish at an early age suggests that there might be a cultural difference

in story grammar between English and Spanish stories. Unfortunately, the current data do not reveal any potential reasons why there may be cultural differences. Future research should be

designed to examine the inclusion of consequence in English and Spanish retells by using equivalent model stories or stories with a standard story grammar format with only one initiating event,

one action, and one problem.

If there is a possibility that differences in the inclusion of consequences exist across languages, there are additional implications to consider. In the United States, a basic episode is typically defined by the inclusion of an initiating event, a related action (or attempt), and a consequence (Hughes, McGillvray, & Schmidek, 1997). Story grammar elements that compose a minimally complete episode typically emerge around 4 years of age for English-speaking children, and 5-year-olds use those structures more frequently (Peterson & McCabe, 1983).

Considering that almost none of the typically developing monolingual SS children, including the 5-year-olds, produced a consequence, an episode analysis should be used with caution for young monolingual SS children. The findings of this study align with those reported by Berman and Slobin (1994), who noted that patterns of narrative macrostructure development appear to differ across languages, particularly for preschool-age children.

Yet another macrostructure finding of interest is that internal response was included more often than initiating events by SS 4-year-olds. This is a significant finding because an awareness and inclusion of emotions is thought to develop later than initiating events for English-speaking children (Hughes et al., 1997) and SS children. For example, Gutierrez-Clellen and Iglesias (1992) reported that 4-year-old SS children rarely reported emotions in their narrative productions. It is possible that different elicitation contexts account for these discrepant findings. In the current study, children were asked to retell a modeled story while referencing pictures, and in the Gutierrez-Clellen and Iglesias study, children watched a silent film and then narrated the events. It is also possible that there are legitimate cultural and/or language factors at play (e.g., Colombian vs. U.S. SS children or Spanish vs. English storytelling) that warrant further examination. In a study reported by Spencer and Slocum (2010), it was noted that one of the 4-year-old SS participants included an internal response more frequently than an initiating event in retell narratives produced in English. It is possible that the inclusion of an internal response is related to issues of limited language or reflects cultural differences that have yet to be reliably documented. Furthermore, it is possible that SS children use an internal response in the place of an initiating event, where the overt statement of an emotion implies that something has happened to cause that emotion. Thus, with young SS children, it may be more appropriate to allow for the liberal interpretation of an episode, acknowledging that an internal response may implicate an initiating event and that a minimally complete episode may be evident conceptually.

Although we found some discrepancies between the story grammar production of our sample of SS children and English-speaking developmental expectations, we also found several consistencies. There are a number of macrostructure features that we would not expect English-speaking children who are 3 to 5 years old to include in their narratives. These later emerging features include the plan and complication. In line with these expectations, our monolingual SS participants did not consistently include these elements either.

Narrative Microstructure

The results of the microstructure analysis suggest that the SS children in the current study produced microstructures similar to those expected of U.S. English-speaking children. Microstructure elements in general were included in children’s retells less consistently than the macrostructure elements. It is reasonable that children develop content in short and simple sentences (e.g., “He looked for his frog. He was sad.”) before producing more complex sentences that include causal and temporal features (e.g., “When he looked behind the log, he saw his frog”). Formulaic markers (e.g., “One day… ”) and temporal markers (e.g., “Then he looked for his frog”) were used more consistently than causal markers and dialogue for all age groups. In addition, our analyses indicated that more 5-year-olds included formulaic markers, temporal markers, and dialogue than 4-year-olds, and more 4-year-olds produced more of these features than 3-year-olds. Also, more 4- and 5-year-olds included causal markers than 3-year-olds, although there was not a significant difference between the percentages of 4-yearolds (54%) and 5-year-olds (55%) who included causal markers.

Unfortunately, our analysis did not differentiate between temporal markers with subordination (e.g., “After he woke up, he couldn’t find his frog”) and temporal markers without (e.g., “He ran and then stopped suddenly”). It is possible that more children across age groups produced temporal markers than causal markers because causal markers typically require subordination and some temporal markers do not require subordination. Although the INC includes a category for narrator evaluation as a microstructure feature, it was not modeled in the story and not typical of fictional retells (Hughes et al., 1997). It is not surprising that only 3% of 3-year-olds and 6% of 5-year-olds included some sort of evaluation.

Our findings confirm a general pattern for both macrostructure and microstructure elements

—that is, older SS children produce more narrative elements than younger children. SS children produced generally the same elements expected of same-age English-speaking children in the United States with the exception of internal response and consequence. We suggest that further examination of these macrostructure features is warranted because they may have an important impact on the identification of language impairment among SS children. The developmental information from this study can help guide the interpretation of narrative assessment for monolingual SS children and can potentially be used to diagnose language disorders in SS children.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The current summary of retell narratives represents an initial attempt to document narrative expectations for young monolingual SS children. In general, the narratives of the current SS participants resemble those of English-speaking children—older children produced more complex narratives than younger children. This is an important finding because it provides evidence that our particular subgroup of SS children produced narratives in a manner that is consistent with findings of previous descriptive narrative studies. This preliminary information contributes to current understanding of Spanish narrative development and can help with the interpretation of the results of narrative assessment for monolingual SS children. Our results indicated that 3-year-old SS children produced stories that contained characters and actions. Four-year-old SS children’s stories were characterized by the use of characters, actions, and internal responses. Five-year-old SS children retold stories containing characters, settings, initiating events, actions, internal responses, formulaic markers, temporal markers, and knowledge of dialogue.

An area that deserves more in-depth investigation is the possible cultural and/or language differences between monolingual SS children in the United States and bilingual children in the United States. Although the present study offers some direction and suggests caution when using an episode analysis for Spanish storytelling, it is uncertain whether U.S. children who speak Spanish would retell stories in a pattern similar to that of monolingual children. It will also be prudent to directly examine SS and English-speaking children in the same study using parallel model stories. Although inferences can be made across studies, more direct comparisons would provide more concrete information about areas of similarity and differences between English and Spanish narratives. Differences in narrative elicitation approaches can impact narrative macrostructure and microstructure, and the results of this study are limited to only one specific narrative elicitation approach. Additional narrative developmental research with SS children that uses different narrative elicitation procedures needs to be conducted.

Finally, future research should offer a closer analysis of microstructure features to ascertain microstructure development. The current study did not distinguish between features that involved subordination and those that did not. Moreover, an index of subordination may offer valuable information about the language characteristics of these children.

REFERENCES

Abild-Lane, T. (1996). Children with early language delay: A group case study of outcomes in the intermediate grades

(Unpublished master’s thesis). Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Applebee, A. N. (1978). The child’s concept of story: Ages two to seventeen. Chicago: The University Chicago Press.

Berman, R. A., & Slobin, D. I. (1994). Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Bishop, D., & Edmundson, A. (1987). Language-impaired 4 year olds: Distinguishing transient from persistent

impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 52, 156–173.

Botting, N. (2002). Narrative as a tool for the assessment of linguistic and pragmatic impairments. Child Language

Teaching and Therapy, 18, 1–21.

Cain, K. (2003). Text comprehension and its relation to coherence and cohesion in children’s fictional narratives.

British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21, 335–351.

Castilla, A. P. (2008). Developmental measures of morphosyntactic acquisition in monolingual 3, 4, and 5 year-old

Spanish speaking children. Toronto: University of Toronto dissertation.

Castilla-Earls, A. P., & Eriks-Brophy, A. (2012). Developmental language measures in Spanish-speaking children.

Revista de Logopedia, Foniatria y Audiologia, 32, e7–e19.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Tomblin, J. B., & Zhang, X. (2002). A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in

children with language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 1142–1157.

Cleave, P. L., Girolametto, L. E., Chen, X., & Johnson, C. J. (2010). Narrative abilities in monolingual and dual

language learning children with specific language impairment. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43, 511–522.

Coloma, C. (2014). Discurso narrativo en escolares de 1° básico con Trastorno Específico del Lenguaje (TEL)

[Narrative discourse in first grade children with specific language impairment (SLI)]. Revista Signos: Estudios

de Linguistica, 3–20.

Curenton, S. M., & Justice, L. M. (2004). African American and Caucasian preschoolers’ use of decontextualized

language: Literate language features in oral narratives. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools,

35(3), 240–253.

Dickinson, D. K., & McCabe, A. (2001). Bringing it all together: The multiple origins, skills and environmental

supports of early literacy. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 16(4), 186–202.

Dunn, L. M., Lugo, D. E., Padilla, E., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Test de vocabulario en imagenes Peabody. Circle Pines,

MN: American Guidance Service.

Elder, C. (2012). Bias in language assessment. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics

(pp. 406–412). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Ellis, E. M., & Thal, D. J. (2008). Early language delay and risk for language impairment. Perspectives on Language

Learning and Education, 15, 93–100.

Ellis Weismer, S. (2007). Typical talkers, late talkers, and children with specific language impairment: A language

endowment spectrum? In R. Paul (Ed.), Language disorders and development from a developmental perspective:

Essays in honor of Robin S. Chapman (pp. 83–101). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fazio, B. B., Naremore, R. C., & Connell, P. (1996). Tracking children at risk for specific language impairment:

A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 52–63.

Fey, M. E., Catts, H., Proctor-Williams, K., Tomblin, J. B., & Zhang, X. (2004). Oral and written story composition

skills of children with language impairment: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Speech-Language-Hearing

Research, 47, 1301–1318.

Fiestas, C. E., & Peña, E. (2004). Discourse in bilingual children: Task and language effects. Language, Speech, and

Hearing Services in Schools, 35, 155–166.

Gillam, S. L., & Justice, L. (2010, September 21). Progress monitoring tools for SLPs in response to intervention

(RTI): Primary grades. The ASHA Leader, 15(11).

Greenhalgh, K. S., & Strong, C. J. (2001). Literate language features in spoken narratives of children with typical

language and children with language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32(2),

114–125.

Griffin, T. M., Hemphill, L., Camp, L., & Wolf, D. P. (2004). Oral discourse in the preschool years and later literacy

skills. First Language, 24, 123–147.

Gutierrez-Clellen, V., & Iglesias, A. (1992). Causal coherence in the oral narratives of Spanish-speaking children.

Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 363–372.

Heilmann, J., Miller, J., Nockerts, A., & Dunaway, C. (2010). Properties of the Narrative Scoring Scheme using

narrative retells in young school-age children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 154–166.

Hughes, D., McGillvray, L., & Schmidek, M. (1997). Guide to narrative language: Procedures for assessment.

Eau Claire, WI: Thinking Publications.

John, S. F., Lui, M., & Tannock, R. (2003). Children’s story retelling and comprehension using a new narrative

resource. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 18, 91–113.

Justice, L. M., Bowles, R., Kaderavek, J. K., Ukrainetz, T., Eisenberg, S., & Gillam, R. (2006). The Index of Narrative

Micro-Structure (INMIS): A clinical tool for analyzing school-aged children’s narrative performance. American

Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 1–15.

Justice, L. M., Bowles, R. P., Pence, K. L., & Gosse, C. S. (2010). A scalable tool for assessing the spoken narratives

of preschool children: The NAP (Narrative Assessment Protocol). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 218–234.

Kaderavek, J. N., & Sulzby, E. (2000). Narrative production by children with and without specific language impairment: Oral narratives and emergent readings. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43, 34–49.

Klecan-Aker, J. S., & Hedrick, D. L. (1985). A study of the syntactic language skills of normal school-age children.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 16, 187–198.

Klecan-Aker, J., & Kelty, K. (1990). An investigation of the oral narratives of normal and language-learning disabled

children. Journal of Childhood Communication Disorders, 5(3), 46–54.

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lahey, M. (1990). Who shall be called language disordered? Some reflections and one perspective. Journal of Speech

and Hearing Disorders, 55, 612–620.

Laing, S. P., & Kamhi, A. (2003). Alternative assessment of language and literacy in culturally and linguistically

diverse populations. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34, 44–55.

Liles, B. Z. (1987). Episode organization and cohesive conjunctives in narratives of children with and without language

disorder. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 30, 185–196.

Mayer, M. (1969). Frog, where are you? New York: Dial Press.

Mayer, M. (1974). Frog goes to dinner. New York: Dial Books for Young Readers.

McCabe, A., & Rollins, P. R. (1994). Assessment of preschool narrative skills. American Journal of Speech-Language

Pathology, 3, 45–56.

McCauley, R. J., & Swisher, L. (1984). Use and misuse of norm-referenced test in clinical assessment. A hypothetical

case. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 49(4), 338–348.

Merritt, D. D., & Liles, B. Z. (1987). Story grammar ability in children with and without language disorder: Story

generation, story retelling, and story comprehension. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 30, 539–552.

Miller, J., & Chapman, R. (2003). Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) (Research Version 8 for

Windows) [Computer software]. Madison: University of Wisconsin, Language Analysis Lab.

Morris-Friehe, M. J., & Sanger, D. D. (1992). Language samples using three story elicitation tasks and maturation

effects. Journal of Communication Disorders, 25(2–3), 107–124.

Muñoz, M. L., Gillam, R. B., Peña, E. D., & Gulley-Faehnle, A. (2003). Measures of language development in fictional

narratives of Latino children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34, 332–342.

Nippold, M. A. (1998). Later language development: The school-age and adolescent years (2nd ed.). Austin, TX:

Pro-Ed.

Nippold, M. A., & Taylor, C. L. (1995). Idiom understanding in youth: Further examination of familiarity and

transparency. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38, 426–433.

Nippold, M. A., Ward-Lonergan, J., & Fanning, J. L. (2005). Persuasive writing in children, adolescents, and adults:

A study of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic development. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools,

36, 125–138.

O’Neill, D. K., Pearce, M. J., & Pick, J. L. (2004). Predictive relations between aspects of preschool children’s

narratives and performance on the Peabody Individualized Achievement Test–Revised: Evidence of a relation

between early narrative and later mathematical ability. First Language, 24, 149–183.

Paul, R. (1991). Profiles of toddlers with slow expressive language development. Topics in Language Disorders, 11, 1–13.

Paul, R. (1996). Clinical implications of the natural history of slow expressive language development. American

Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 5(2), 5–21.

Paul, R. (2000). Predicting outcomes of early expressive language delay: Ethical implications. In D. V. M. Bishop &

L. B. Leonard (Eds.), Speech and language impairments in children: Causes, characters, intervention and outcome,

(pp. 195–209). Hove, England: Psychology Press.

Paul, R., Hernandez, R., Taylor, L., & Johnson, K. (1996). Narrative development in late talkers: Early school age.

Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 99–107.

Paul, R., Murray, C., Clancy, K., & Andrews, D. (1997). Reading and metaphonological outcomes in late talkers.

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40, 1037–1047.

Paul, R., & Smith, R. (1993). Narrative skills in 4-year-olds with normal, impaired, and late-developing language.

Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 592–598.

Petersen, D. B., Gillam, S., & Gillam, R. (2008). Emerging procedures in narrative assessment: The Index of Narrative

Complexity. Topics in Language Disorders, 28, 115–130.

Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012). The Narrative Language Measures: Tools for language screening, progress

monitoring, and intervention planning. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 19(4), 119–129.

Peterson, C., & McCabe, A. (1983). Developmental psycholinguistics: Three ways of looking at a child’s narrative.

New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Rescorla, L. (2002). Language and reading outcomes to age 9 in late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and

Hearing Research, 45, 360–371.

Restrepo, M. A. (1998). Identifiers of predominantly Spanish-speaking children with language impairment. Journal of

Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 1398–1411.

Rice, M., Taylor, C., & Zubrick, S. (2008). Language outcomes of 7-year-old children with or without a history of late

language emergence at 24 months. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51, 394–407.

Rojas, R., & Iglesias, A. (2009). Making a case for language sampling. The ASHA Leader, 14(3), 10–11.

Scott, C. M. (1988). Producing complex sentences. Topics in Language Disorders, 8, 44–62.

Scott, C. M., & Windsor, J. (2000). General language performance measures in spoken and written narrative and

expository discourse of school-age children with language learning disabilities. Journal of Speech, Language,

and Hearing Research, 43, 324–339.

Speece, D. L., Roth, F. P., Cooper, D. H., & de la Paz, S. (1999). The relevance of oral language skills to early literacy:

A multivariate analysis. Applied Psycholinguistics, 20, 167–190.

Spencer, T. D., & Slocum, T. A. (2010). The effect of a narrative intervention on story retelling and personal story

generation skills of preschoolers with risk factors and narrative language delays. Journal of Early Intervention,

32(3), 178–199.

Stein, N., & Glenn, C. (1979). An analysis of story comprehension in elementary school children. In R. D. Freedle

(Ed.), Advances in discourse processes: Vol. 2. New directions in discourse processing (pp. 53–119). Norwood,

NJ: Ablex.

Strong, C., & Shaver, J. (1991). Stability of cohesion in the spoken narrative of language impaired and normally

developing school-aged children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34, 95–111.

Tomblin, J. B., Zhang, X. Y., Buckwalter, P., & O’Brien, M. (2003). The stability of primary language disorder: Four

years after kindergarten diagnosis. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 46, 1283–1296.

Ukrainetz, T. A., & Gillam, R. B. (2009). The expressive elaboration of imaginative narratives by children with specific

language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 883–898.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012 (131st ed.). Retrieved from http://www.

census.gov/compendia/statab/

Wagner, R. C., Nettelbladt, U., Sahlén, B., & Nilholm, C. (2000). Conversation versus narration in pre-school

children with language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 35,

83–93.

Westby, C. (1984). Development of narrative language abilities. In G. Wallach & K. Butler (Eds.), Language learning

disabilities in school-age children (pp. 103–127). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Westby, C. (1991). Learning to talk – talking to learn: Oral-literate language differences. In C. S. Simon (Ed.),

Communication skills and classroom success (pp. 181–218). San Diego, CA: College-Hill.

APPENDIX

Story Script

(Página 1) Había una vez un niño que tenía 3 mascotas: el perro, la tortuga y la rana saltarina. Los 4 pasaban mucho tiempo juntos y se divertían. Una noche el niño se preparaba para salir a comer con su familia. Las mascotas estaban muy tristes porque el niño no las podía llevar con él. (Página 2) Cuando el niño se estaba despidiendo del perro y de la tortuga, la rana saltarina

dio un brinco y se escondió en la chaqueta. (Página 3) El niño se fue sin darse cuenta de que la rana estaba en su bolsillo. (Páginas 4–5) La familia llegó a un restaurante muy bonito y elegante donde todas las personas estaban vestidas para la ocasión. (Página 6–7). Mientras el mesero (camarero) les preguntaba qué querían comer, la rana decidió dar un paseo. Miró a su alrededor y dio un gran brinco. (Página 8) La rana cayó dentro del saxofón. Todos se preguntaban por qué el saxofón sonaba tan mal «No sé, pero voy a revisarlo», dijo el músico. (Página 9) En ese momento ¡suas! la rana le cayó justo en la cara. El músico sorprendido y asustado se fue para atrás y cayó dentro del tambor y lo rompió. (Páginas 10–11) Los músicos quedaron confundidos sin saber qué había pasado. Solo vieron algo verde que volaba. La rana saltarina aprovechó la confusión y dio un gran salto cayendo en un plato de ensalada. (Páginas 12–13) Resulta que la ensalada donde estaba la ranita iba para una señora muy elegante. Cuando empezó a comer ¡suas! se encontró a la ranita. (Páginas 14–15) «¡Auxilio, auxilio! ¡hay una rana en mi plato!». Y la rana brincó de nuevo para escaparse cayendo en una copa de un señor gordo y con bigote.

(Página 17) Al tomar el agua el señor, la rana saltó de la copa y ¡mua! besó al señor en la nariz. (Página 18) «¿¡Con que aquí estás, rana!?» dijo el mesero (camarero). «Todo este desorden es por tu culpa”. (Páginas 20–21) La agarró de las patas para sacarla del restaurante. «No puede ser, es mi rana. ¿Qué hace aquí?», dijo el niño. (Páginas 22–23) «Señor, señor, no se la lleve por favor, es mi amiga la rana» dijo el niño. Los familiares lo miraban muy confundidos y enojados. «En este restaurante no nos gusta tener ranas. Llévensela inmediatamente”, dijo el mesero (camarero) muy enfadado. (Páginas 25–26) Al regresar a casa todos estaban enojados porque la rana dañó (estropeó) la noche. La ranita se sintió muy mal al darse cuenta de que los había molestado con su travesura. (Páginas 27–28) «Tú y tu dichosa rana. Llévatela ahora mismo para tu cuarto,» dijo el papá. El perro y la tortuga no entendían qué pasaba. (Página 29) Cuando llegaron al cuarto recordaron todas las travesuras de la rana: el saxofón, el tambor, la ensalada, la copa y el beso. Todo había sido muy chistoso (divertido). El niño y la rana se rieron sin parar.

Y colorín colorado este cuento se ha acabado.

English Translation of Spanish Script

(p. 1) Once upon a time, there was a boy who had 3 pets: a dog, a turtle and a jumpy frog. The four of them spent a lot of time together and had a lot of fun. One night, the boy was getting ready to go for dinner with his family. The pets were very sad because the boy couldn’t take them with him. (p. 2) When the boy was saying good bye to the dog and the turtle, the jumpy frog jumped and hid in the boy’s jacket. (p. 3) The boy left without realizing that the frog was in his pocket. (pp. 4–5) The family went to a very pretty and elegant restaurant, where everyone was dressed very nicely. (pp. 6–7) While the waiter took their order, the frog decided to take a stroll. The frog looked around and took a big hop. (p. 8) The frog landed in a saxophone. Everyone was wondering why the saxophone was making that noise. “I don’t know, but I am going to check it out,” said the musician. (p. 9) Right then, the frog fell on his face. The surprised musician fell backwards on the drum and broke it. (pp. 10–11) The musicians were confused and did not know what had just happened. They saw something green flying. The jumpy frog took advantage of the confusion, took a big hop and landed on a plate of salad. (pp. 12–13) It just so happened that the salad where the frog landed belonged to a very elegant lady. When she began to eat, she found the frog (pp. 14–15) “Help, help! There is a frog on my plate!” And the frog hopped again to avoid landing on the glass of a big man with a mustache. (p. 17) At the moment the man was going to take a sip from his glass, the frog hopped from the glass and kissed the man on his nose. (p. 18) “So here you are, frog!?” said the waiter. “All this mess is because of you.” (pp. 20–21) He took the frog by his legs to carry it out from the restaurant. “This cannot be happening, that is my frog. Why is it here?” said the boy. (pp. 22–23) “Sir, sir, don’t take it, it is my friend the frog,” said the boy. The boy’s family was very upset and confused. “We don’t like frogs at this restaurant. Please take it with you immediately,” said the waiter very angrily. (pp. 25–26) On the way back home, everyone was very upset because the frog ruined their night. The frog felt bad when he realized that he had ruined everyone’s night with his mischievous act. (pp. 27–28) “You and your frog. Take it to your room right now,” said the father. The dog and the turtle did not understand what was going on. (p. 29) When they got to their room, they remembered all the funny things: the saxophone, the drum, the salad, the glass, and the kiss. All of that was very funny. The boy and the frog laughed a lot. The end. Note. Text published with author and editor’s authorization. The original source in Spanish: Castilla-Earls & Eriks-Brophy, 2012. Translation provided for content information purposes.