Douglas Petersen

Department of Communication Disorders, University of Wyoming

Laramie, WY

Trina D. Spencer

Institute for Human Development, Northern Arizona University

Flagstaff, AZ

Financial Disclosure: Douglas Petersen is an Assistant Professor at the University of Wyoming.

Trina Spencer is Research Director at Northern Arizona University.

Nonfinancial Disclosure: Douglas Petersen has previously published in the subject area.

Trina Spencer has previously published in the subject area.

Abstract

The majority of children who are culturally and linguistically diverse in the United States

read below grade level. This disproportionate prevalence of reading difficulty is likely due to

language-related factors. Although most of these children do not have language

impairment, they do need explicit instruction in the use and comprehension of complex,

academically-related language that is expected in public schools. Speech-language

pathologists (SLPs) are particularly well suited to help guide this needed explicit language

instruction and help implement language progress monitoring. In this clinical tutorial, we

propose ways in which narrative assessment and intervention within a response to

intervention framework can be carefully aligned and realistically carried out. We propose

that narrative assessment and narrative intervention should become standard practice in

schools to monitor language growth and provide explicit language instruction to students.

Narrative Assessment and Intervention: A Clinical Tutorial

How we define a problem usually determines how we analyze it. It sends us in a particular

direction. And how we analyze a problem — the direction we take — absolutely determines

whether we find a solution and what the quality of that solution is. (Jones, 1998)

Clearly defining a problem is an important first step in finding the solution to that problem. It is much more difficult to solve a problem that is not well understood than to solve a problem that has been clearly defined and analyzed. The way a problem is expressed and understood has a major impact on the outcomes of the proposed solutions. In this clinical tutorial, we first clearly define the nature of a significant problem many of the children in public schools face today—reading difficulty due to language-related factors. We then propose ways in which analyses and solutions to that problem can be carefully aligned and realistically carried out.

Defining the Problem

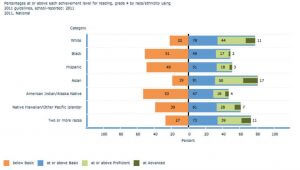

The reading performance of fourth grade students, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), is troublesome, especially for children who are culturally and linguistically diverse. From an academic perspective, children who are culturally and linguistically diverse include those who come from a culture where their language or dialect does not match the language or dialectal expectations of the U.S. education system. In 2011, over 80% of African American, Hispanic, and American Indian children performed below grade level in reading, and nearly 50% of these fourth grade students could not read at a basic level (NAEP, 2011; see Figure 1). This alarming problem may on the surface appear to be well-defined — the NAEP purports to assess reading, but as Kamhi (2007) stressed in his narrow view of reading, the term reading is often used to describe two distinct constructs: decoding and language comprehension. Kamhi proposed that reading should be defined as the process of decoding written words, and reading comprehension should be defined by the construct that it pertains to— language comprehension (2009a, 2009b). Figures 2 and 3 depict these two constructs and highlight the way in which they are employed when the communication modality is speech (Figure 2), and when the communication modality is writing (Figure 3). Note that the only difference between oral language comprehension in Figure 2 and written language comprehension (reading comprehension) in Figure 3 is the modality by which the message is initially encoded and expressed. After we “break the code,” be it speech or writing, and convert that code to language, our language comprehension facility is what determines whether we comprehend the meaning of the message. By using the narrow view of reading, and clearly defining reading as the initial decoding of a written message, we can then clearly define reading comprehension for what it is, which is language comprehension. When these decoding and comprehension constructs are conflated into a single label, as is the case traditionally, there is a lack of clarity in the problem, and consequently a lack of clarity for assessment and treatment.

Figure 1. National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) for reading by race/ethnicity in 2011

As a prime example, it is unclear if children who are culturally and linguistically diverse who are performing poorly on state and national reading assessments have unusual, disproportionate difficulty with decoding, language comprehension, or both. Without question, there are children who perform poorly on these assessments because they have difficulty with decoding, but research has indicated that children who are culturally and linguistically diverse do not have unusually high rates of difficulty learning to decode, nor do they have unusually high rates of dislexia (Nakamoto, Lindsey, & Manis, 2007; Petersen & Gillam, in press; Shaywitz, Escobar, Shaywitz, Fletcher, & Makuch, 1992). For example, Nakamoto et al. (2007) followed 261 Spanish-speaking, English language learners from second grade to sixth grade and found that the children’s decoding ability did not fall behind a normative sample of native English-speaking children. Reading comprehension, on the other hand, was significantly below the norm. Reading comprehension difficulty that is not associated with difficulty decoding written words implicates a language problem.

Clarifying the Language Problem

When identifying language problems that relate to a student’s academic performance, professionals may speculate about possible language impairment. Although language impairment is always a possibility, language impairment, similar to dislexia, appears to follow a normal distribution, with about 7% of the population qualifying for that designation (Tomblin et al., 1997). It is not expected that language impairment would be more prevalent among one ethnicity over another (Leonard, 1987). This suggests that the language-related problem must be defined so that it accounts for disproportionate, poor performance across a diverse group of children.

There are many reasons why a child’s language comprehension performance can be considered inadequate. Language impairment is clearly one reason, but lower socioeconomic status (SES), mother’s level of education, limited English language proficiency, inadequate instruction, dialectal differences, and cultural differences can all lead to language comprehension that is below what is expected of children enrolled in public education (Francis, Rivera, Lesaux, Kieffer, & Rivera, 2006; Hart & Risley, 1995; National Governors Association for Best Practices [NGA Center] & Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO], 2010; NICHD, 2005; Snow, Porche, Tabors, & Harris, 2007). The disproportionately lower reading performance that reading assessments, such as the NAEP Assessment Tool (2011) report is likely a measurement of the extent to which all of these language-impacting factors, including culture, dominant language, and dialect, shift language away from academic expectations. It is no wonder, then, that those children who have the most difficulty with reading comprehension are the same children who have a greater number of factors that mismatch their language with the academic language emphasized at school. Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) have much to offer in helping children develop language that aligns more closely with school expectations. ASHA’s 2010

document on roles and responsibilities of SLPs in schools clearly states that:

SLPs provide a distinct set of roles based on their focused expertise in language. They

offer assistance in addressing the linguistic and metalinguistic foundations of curriculum

learning for students with disabilities, as well as other learners who are at risk for school

failure, or those who struggle in school settings. (pg. 1)

It is important to note that we are not making ethnocentric or cultural superiority statements. Any language, culture, or dialect is no less important than any other. We are instead talking about helping all children, including typically developing children who are culturally and linguistically diverse, learn to understand and produce the academic language necessary to function in an academic context in the United States.

For children in the public school system, language impairment is present when a child has an unusual difficulty learning language and their language performance is deemed inadequate in a functional, academic context (IDEA, PL 108-446, 2004). This functional, academic approach to identifying children with language difficulty in schools can be extended to children who, for whatever reason, demonstrate language skills that are below expectations (i.e., not functioning as expected in an academic setting). The monitoring of decoding progress and explicit decoding instruction tailored to students’ individual needs is common place in public schools today. This decoding progress monitoring and individualized instruction is often applied to all children, including those who do not have an identified disability. This has not been the case for language assessment and instruction. From our clinical experience, it is clear that it is still not standard practice in schools to monitor language growth or provide explicit language instruction to students. The consequences of this gross oversight are clearly manifested in the poor performance on the high stakes reading assessments children are expected to take each year. Fortunately, the climate is changing. Recent paradigm shifts from “wait to fail” models of service delivery to prevention and early intervention (e.g., Response to Intervention [RTI]), and the widespread adoption of the Common Core State Standards (NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010), which have a considerable emphasis on the comprehension of complex oral and written language, bring many opportunities for SLPs to fully embrace their roles and responsibilities in public schools.

The traditional focus on children with language impairment underutlizes the SLPs’ language expertise. Many SLPs spend their time absorbed in the treatment of children with identified disabilities and the management of meetings and paperwork associated with those students. Although the work associated with these students is important, necessary, and fulfilling, it is incomplete and discordant with a contemporary early identification and preventative philosophy. The recent roles and responsibilities document highlights the morphing of SLPs’ tasks toward prevention and early intervention (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2010). We believe that all children deserve a special education. A special education means that children receive an education that is tailored to their specific needs, even if their needs are related to cultural or linguistic diversity, and not disorder. We predict that in the near future, schools will turn to SLPs for leadership in ensuring all school-age children develop a strong language foundation for academic success. We do not expect that SLPs will provide intervention to all children directly, but that they will be the conductors of multi-tiered orchestras of language promotion for all children

The SLP’s Purview

Children With Language Impairment

Children with language impairment have unusual difficulty learning and using language, and are almost always in need of a more robust language foundation for academic success (Aram & Hall, 1989; Johnson et al. 1999; Snowling & Hulme, 1989; Stothard, Snowling, Bishop, Chipchase, & Kaplan, 1998) . These children have been the primary focus of the SLP. Children with language impairment can receive special services in the public school system only if their language difficulties adversely impact their education. It is this functional perspective, once again, that should drive services. Setting labels aside, what is important is that they need treatment from an expert to succeed.

Typically Developing Monolingual Children from the Dominant United States Culture

Our school system requires children to understand and use complex language that is not often encountered in typical conversation. Language can vary along a continuum of formality. At the most informal end lies oral conversation between two friends (e.g., about ongoing events). At the other end of the spectrum lies written language (e.g., an essay intended for an unfamiliar audience about a scientific experiment). All children must learn to understand and use the more formal, literate language that is most salient in the classroom curriculum and literature. Much of this formal language is introduced and acquired in the school setting. Any child who is having difficulty understanding and using this literate language should be entitled to help as part of their right to a free and appropriate public education. Typically developing monolingual English-speaking children could have difficulty with functional, literate language because of multiple factors, including socioeconomic conditions, poor instruction, or lack of adequate exposure or motivation to engage in academic endeavors. Any language difficulty for any reason substantiates a need for intervention so that these children can succeeed academically. These typical language learners may not require extensive interventions provided directly by an SLP; nevertheless, explicit, evidence-based instruction should be available to them, and an SLP can be a valuable resource regarding the direction and execution of such language instruction. The

SLPs role may be that of a coach or member of an instructional support team that redefines the child’s instructional experience and the general education interventions applied. This appropriate application of the SLP’s role will ehnance insruction for all children and is in-line with ASHA’s recent emphasis on interprofessional collaboration (ASHA, 2013).

Typically Developing Children Who Are Culturally and Linguistically Diverse

Children who are learning English as a second language, or who come from a culture where their language or dialect do not match the language or dialectal expectations of the U.S. education system, may also be in need of an enhanced English language foundation for academic success in our school system. Even if the language of instruction is not English (which for the vast majority of children it is), high-stakes assessments will demand proficient English language from all students. English learners do not meet the classification of language impairment because they do not have unusual difficulty learning language, yet they often have the other half of the definition well covered; their English language proficiency or their facility using and/or understanding the language and dialect expected in the school system is not yet sufficient to successfully function in an academic setting. These typically developing children often require additional language support over and above typically developing monolingual English-speaking children. Although SLPs have historically had little involvement with this group of students, their expertise in language assessment and intervention could be well applied. Co-teaching, or consulting with English language learner (ELL) teachers and/or literacy or Title 1 teachers, may be a way for SLPs to enhance general education services provided to these students.

Children With Language Impairment Who Are Culturally and Linguistically Diverse

Children who have language impairment and who are culturally and linguistically diverse comprise a fourth group of children who need supplemental language support. These children present with a complicated profile. They have unusual difficulty learning and using language (any language), and simultaneously acquiring English as a second language, literate language, or a specific dialect used in the academic setting. They fit the criteria for the two preivous subgroups and because of this, classification for these children can be difficult (i.e., correctly identifying a language impairment). However, what is clear is that regardless of classification, they need supplemental language support provided directly by the SLP, but again collaboriate models with ELL and general education teachers is advised for a comprehensive intervention approach.

Response to Intervention and Language

All of the children described above have one thing in common; they need an enhanced language foundation to succeed academically. It is important to identify those children who are having difficulty acquiring academically-related language as early as possible, and to intervene accordingly, with a preventative focus. RTI is a contemporary framework for early intervention, prevention, and valid disability identification. RTI has prompted a shift from the traditional general-special education dichotomy to a graduated model of differentiated instructional delivery designed to meet the individual needs of all students. The key concept of this model is that each student’s own performance level and progress (or lack thereof) over time is used to determine need as opposed to static performance level only. The logic follows that students who are low in some academic content and do not make gains given high quality instruction will need high quality supplemental intervention to meet academic benchmarks; however, students who are low but make adquate progress in a brief instructional period do not need intensified intervention to meet benchmarks. The responsiveness of each student with respect to high quality instruction/ intervention marks the essence of RTI and is consistent with the construct assessed through

dynamic assessment (Feuerstein, 1980; Grigorenko, 2009; Gutierrez-Clellen, & Peña, 2001). Using a dynamic format, such as in RTI, environmental, cultural, dialectal, and second language causes for language limitations, can be effectively ruled out prior to eligibility determination.

Intervention

All RTI models consist of two major components: research based instruction and valid assessment of curriculum-relevant behaviors. With regard to instruction, this model applies to an entire student population through a conceptual organization of instructional tiers. Assessment results are critical for making decisions regarding whether students should remain in the current tier of intervention or be figuratively moved to a more or less intense tier (Marston, 2005). For RTI models of language development to be successful, the intervention context and language targets should be directly and clearly related to the academic curriculum in schools.

Intervention procedures need to be adaptable across varying levels of intensity, and prescriptive enough that educators other than SLPs can deliver them, especially at tier 1 (e.g., classroom) and tier 2 (e.g., small group). It is neither necessary nor feasible for most SLPs to be the direct teachers. That being said, it is necessary and feasible for most expert language professionals to be designers and leaders of RTI language interventions. Most teachers and reading professionals do not have sufficient language training to know how to measure language and to determine what language targets should be addressed in intervention. Collaborative relationships among SLPs and general educators, including classroom teachers, literacy teachers, ELL teachers, librarians, and others involved in general eduction instruction will be essential to bring tiered language intervention to scale across multiple tiers.

Assessment

The second major component of RTI is valid assessment used to determine which students receive intensified intervention (tier 2/tier 3) and when intervention is no longer needed. In a broader landscape of assessment, there are different types of instruments intended for different purposes of assessment. For screening or special education eligibility, standardized, norm-referenced tests are most often employed. For instructional planning and progress monitoring, educators typically use criterion-referenced tests such as unit tests or curriculumbased assessments. In RTI models where all students participate, efficient and economical assessment procedures are necessary. One way of making assessment realistic in an RTI context is to derive multiple critical functions from the same assessment results and from the same test. For instance, RTI’s chief assessment functions are identification of children with additional needs (i.e., screening) and progress monitoring. Both purposes can be fulfilled using curriculum-based measurement (CBM) strategies (Deno, 2003; Jenkins, Hudson, & Johnson, 2007). This type of assessment allows for universal screening of all children on a quarterly basis and a more frequent schedule of monitoring for those who are identified as needing more intensive instruction. The same CBM tool is used for both purposes. Special education eligibility and instructional planning are secondary assessment functions in an RTI model. Even so, in many RTI models the CBM tools used for screening and progress monitoring are also used for intervention planning and incorporated into special education evaluations.

CBM tools feature several characteristics that promote their efficient and effective use in RTI systems: (a) they have adequate validity and reliability, (b) parallel forms facilitate repeated sampling of student performance, (c) they need to be quickly and easily delivered and scored following standardized procedures, (d) the measures need to be sensitive enough to capture growth over time (i.e., responsiveness), and (e) CBM tools need to reflect socially important outcomes (Deno, 2003; Deno, Mirkin, & Chiang, 1982; Missall & McConnell, 2004).

Innovative Assessment and Intervention

There are considerable challenges to an RTI framework for language. The most critical is that language is generative and complex. It is not used or validly assessed in a fractionalized, discrete, decontextualized manner (Haynes & Pindzola, 2012). The complexity of language, and the lack of quick and reliable language assessments inhibits the successful promotion of language in schools outside the SLPs office. However, to execute an RTI model with language, a suitable approach needs to be developed, one that involves the efficient assessment of academically-important language skills and leads to explicit, target-focused language interventions across varying tiers of intensity for children with diverse language needs (Ukrainetz, 2006a).

Therory and empirical evidence suggest that narrative discourse may be an excellent context and focus for language assessment and intervention for RTI. Narratives (stories) are the telling of real or imaginary past events (Labov, 1972; Moffett, 1968). From a functional perspective, narratives serve a highly communicative and social function at home and at school. Narratives are inherent to social interactions and ways of conceptualizing the world (Bruner, 1986; Nelson, 1991). Narratives are listened to and produced by children frequently (McCabe, 1991). Children hear and tell stories in many settings, including at home, in the classroom, and at play. Through narrative, history and culture are maintained, community is regulated, and children are socialized (Bauman, 1986; Saleebey, 1994). Academically, narratives provide a bridge between oral and written language (Gillam & Johnston, 1992; Westby, 1985; 1999). Narration requires the use of complex, literate-like language that is decontextualized. Some linguistic features that have been identified as important for a literate style of narration are coordinating conjunctions, elaborated noun phrases, causal and temporal subordinating conjunctions, adverbs, and metalinguistic terms (Eisenberg et al., 2008; Greenhalgh & Strong, 2001; Nippold, 1998; Nippold, & Taylor, 1995; Nippold, Ward-Lonergan, & Fanning, 2005; Strong & Shaver, 1991; Ukrainetz & Gillam, 2009; Ukrainetz et al., 2005; Westby, 1999). Children who are competent at narration tend to do well in school (Griffin, Hemphill, Camp, & Wolf, 2004). Narrative outcomes are embedded in the Common Core State Standards and are essential to reading comprehension and writing instruction (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zang, 2002; Dickinson & McCabe, 2001; NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010).

RTI and Narrative Assessment

Frequent, brief narrative language samples elicited using a structured retelling task have considerable potential to fulfill the primary functions of screening and progress monitoring in RTI systems for language (Gillam, Olszewski, & Segura, 2011; Heilmann et al., 2008; Heilmann, Nockerts, & Miller, 2010; Petersen & Spencer, 2012; Tilstra & McMaster, 2007). Short narrative retells can take very little time to administer, and there is emerging evidence that narrative retells can be scored in real time (Gillam & Pearson, 2004; Pence, Justice, & Gosse, 2007; Pettipiece & Petersen, 2013; Petersen & Spencer, 2012). Furthermore, narration is a form of language discourse with a relatively transparent degree of validity. Narratives are, after-all, language samples; and more importantly, narratives are language samples that require complex language that very closely reflects the language children are required to understand and produce in school in both oral and written modalities. Narrative language sample analyses lend themselves to discrete measurement of key story structures and linguistic features — all derived from cohesive discourse. Narrative retells require an integration of listening comprehension, short-term memory, cognitive organization, and expressive language, which makes it an ideal proxy for general language abilities as they relate to academic achievement. Detailed analysis and examination of brief narrative retells can facilitate intervention planning by identifying story grammar and literate language features absent in children’s stories. Consistently low performance over time on narrative retelling despite adequate narrative instruction may indicate that further eligibility testing is required.

To be useful in an RTI context, a measure of narrative language would need to conform to CBM conventions (Deno, 2003). These include quick and easy standardized administration and scoring procedures, repeated sampling using parallel forms, and the results should inform intervention decisions.

Brief narrative samples have been shown to be reliable for the measures of total number of words, C-units, and clauses (Tilstra & McMaster, 2007). Heilmann et al. (2008) collected 3.5–6 minute narrative samples ranging from 35 to 70 utterances. Analyses of the narratives indicated that narrative language samples can be fast and efficient, while allowing the clinician to reliably assess children’s linguistic proficiency. Most recently, Pettipiece and Petersen (2013) reported excellent inter-rater reliability for scoring brief narratives in real-time. In addition to reliability, the validity of brief measures of narration appears to not be particularly impacted. Heilmann, Nockerts, and Miller (2010) divided 11-minute language samples into 1-, 3-, and 7-minute sections. No significant variances were found in relation to total number of utterances, words per minute, number of different words, and mean length of utterance when examined per minute. In a similar study, Shawhan and Petersen (2013) compared short narrative retells that took approximately one minute to elicit to lengthier narrative retells elicited from the wordless picture book Frog Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969). Results indicated that measures of mean length of utterance, number of different words in proportion to the total number of words, words per minute, subordination, and story grammar were not significantly different between the short and long narratives. Standard administration of the short narratives involved the examiner reading a short story to school-age children and asking them to retell the story. While children retold the story, the examiner used a story-specific scoring guide to score. The scoring guide included story grammar elements (character, setting, problem, emotion, plan, attempt, consequence, ending, and end feeling) and language complexity (use of then, when, after, and because). Administration lasted between 1–2 minutes for each narrative retell and scoring did not require additional transcription and analysis.

Parallel forms are just beginning to emerge for narrative assessment procedures and the preliminary psychometric evidence is promising (Petersen & Spencer, 2012). In narrative intervention studies using multiple-baseline designs (e.g., Brown & Petersen, 2010; Petersen, De George, Zebre, Ukrainetz, & Spencer, 2011; Petersen, Gillam, Spencer, & Gillam, 2010; Spencer & Slocum, 2010), the feasibility of constructing narratives of equivalent complexity is evidenced in the highly stable baselines obtained across several research participants. Recently, in a narrative intervention study with preschool children with disabilities, a retell task was the primary outcome and the elicitation stimuli included 40 different short stories with equivalent length and complexity (Spencer, Kajian, Petersen, & Bilyk, in press). Each of the stories served as a parallel form so that changes over time could be attributed to actual language gains and not variations in the stories.

Narrative assessment can directly inform intervention. Multiple studies have shown that deficits noted in narration can be specifically targeted in intervention (Petersen, 2011). In one such example, Weddle, Kajian, Spencer, and Petersen (2013) used the results of a narrative retell measure to differentiate the focus of their intervention for specific children within the groups and to select intervention targets for each child individually.

Although more psychometric analyses are needed and large-scale studies with proximal and distal outcomes are warranted, the current body of research positively indicates that narrative assessment is a viable approach to language assessment in an RTI context. Narrative assessment, with recent innovations, appears to meet the curriculum-based measurement requirements outlined by Deno (2003), and fit within the SLPs roles and expertise with language and literacy.

RTI and Narrative Intervention

State and national reading assessments clearly indicate that a large percentage of children in our schools need additional help understanding the complex language they are required to read. Teaching children to comprehend written language cannot take place very effectively for most young children because they still do not know how to access the written code (decode) and convert it into fluent language. This means that teaching children to comprehend the complex language that they access from written language has to be put on hold until children can actually access that written language. However, because reading comprehension is essentially the same construct as oral language comprehension, oral language can be bolstered at an early age with the explicit purpose of laying a foundation for future reading comprehension success. Because narratives require complex language that is reflective of written language, they can be an excellent language intervention medium. In narrative intervention, narratives can be the target of intervention, as well as the context of language intervention. This is particularly important because narratives are not only a general outcome measure of academically relevant language; they are also able to directly guide intervention. Narrative intervention can be shaped directly from narrative assessment results, with a clear and perfect correspondence between what is found to be lacking in assessment and what is targeted in treatment.

Narrative intervention can be implemented in a multi-tiered fashion so that children can be placed in an appropriate intensity of intervention. Narrative intervention is a flexible approach to language intervention, and research has clearly demonstrated its efficacy with a broad range of children with diverse language needs (Gillam & Olszewski, 2010; Hayward & Schneider, 2000; McGregor, 2000; Petersen, 2011; Petersen et al., 2010; Spencer & Slocum, 2010; Spencer & Petersen et al., in press).

A narrative intervention is typically constructed around whole activities so that language can be learned and applied in a functional, academically-related context. When language instruction is provided in a manner that is related to classroom instruction, transfer and generalization are more likely to occur. School-age language and its related areas should be taught with a combination of explicit, systematic instruction and meaningful contexts that engage students (Ukrainetz, 2006b). Functional use and skill drill can cycle back and forth between more complex whole activities that highlight the target skill but also involve other skills and simple part activities that involve only the target skill. A contextualized intervention, like narrative intervention, combines the best elements of teacher-directed and child-oriented interventions in an intesive manner with deliberate practice (Fey, 1986; Ukrainetz, 2006b). The ultimate objective is to systematically withdraw support to foster student independence.

To be implemented in RTI systems, narrative intervention needs to be delivered in a variety of arrangements such as large group, small group, and individually. In addition, educators other than the school-based SLPs need to serve as interventionists. Gillam and Olszewski (2010) evaluated the impact of narrative and vocabulary instruction provided by an SLP to a first grade classroom of typically-developing children and children at risk for academic failure. Results indicated that children in the experimental group demonstrated greater improvement in narrative and vocabulary skills when compared to children in a classroom that did not receive intervention. Spencer, Petersen, Slocum, and Allen (in press) examined the effects of a narrative intervention delivered by Head Start teachers to a whole class of preschool students. More than half of the participants were ELLs. Results indicated statistically significant differences on narrative retell and comprehension measures between the intervention and control groups. Importantly, the intervention was just as effective for the ELLs as it was for the English speaking children.

Petersen (2011) conducted a systematic review of narrative intervention and found strong effect sizes for individual and small group arrangements. Most recently, several studies have been carried out using narrative intervention as an independent variable. As an example of a recent small group narrative intervention, Spencer and Slocum (2010) implemented a small group narrative intervention with preschoolers who demonstrated delayed language. Intervention was delivered to four children at a time. Using a multiple-baseline design study, results indicated meaningful, efficacious changes due to the intervention. Improvements were noted in both the story grammar and language complexity produced by the participants. S. L. Gillam, Gillam, and Reece (2012) investigated the efficacy of a small-group, contextualized language intervention using narratives with sixteen children. Results indicated that children in the treatment group made statistically significant gains on sentence and discourse level measures when compared to children in a control group. Narrative interventions have also been investigated in a one-on-one arrangement with school age children with significant language needs (Petersen et al., 2010; Petersen et al., in review) and preschool children with developmental disabilities (Spencer, Kajian, et al., in press). In all three studies, researchers employed multiple baseline design studies that involved frequent repeated elicitation of narrative retells. Results indicated that the one-on-one intensive narrative intervention had a large impact on the participants’ use of story grammar and language complexity features.

In a recently completed study designed to examine the efficacy of narrative intervention in an RTI context, Head Start teachers and paraprofessionals delivered narrative interventions to their students in a whole class format, in small groups, and individually based on the students’ retell performances over time. Results indicated that the same high level of efficacy was noted as when researchers delivered the interventions (Weddle, Zitting, & Spencer, 2013). These variations in narrative intervention, provided in large group, small group, and individual settings, suggest that narrative intervention can effectively be adjusted to meet the criteria for tiered RTI intervention.

In all of the narrative intervention studies described above, explicit teaching principles undergirded the procedures. It stands to reason that if narrative intervention will fulfill a clinical need in schools as the context and focus of language intervention, story grammar and language complexity need to be taught explicitly with manualized steps to ensure the integrity of the implementation. Explicit teaching involves a number of strategies, but those featured in many of the narrative intervention studies included: (a) many opportunities for children to respond, (b) systematic scaffolding of visual materials, (c) immediate corrections, and (d) least restrictive prompting and prompt fading to build independence (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Petersen, 2011).

Children learn best when they have repeated practice engaging in the target behaviors. A fast paced narrative intervention that encourages all the children to respond together as a group or through individual turns has the potential of increasing learning and decreasing disruptions (Heward, 1996; Spencer, Petersen, et al., in press). In many of the narrative interventions mentioned above, regardless of group size, pictures and icons representing each story grammar element were used for teaching. They were faded within sessions to increase the independence of children’s story telling. Although pictures are helpful for teaching, they often do not exist in the natural environment when language and storytelling activities are expected. Therefore, we recommend that pictures be faded in an intentional manner.

Contingent feedback and corrections are consistently identified as important elements of evidence-based practices in education (Simonsen, Fairbanks, Briesch, Myers, & Sugai, 2008). It is important that corrections are not too far removed from the mistake. Storytelling is learned like a sequential chain. For example, one element of the story cues the next element. If errors are allowed to occur, then the error could become the cue not the correct element. In many of the narrative interventions described above, corrections and prompts were indistinguishable. Interventionists should not use more restrictive prompts when they are not necessary. The goal is to build independent storytelling skills and if interventionists provide too much prompting, that goal can be inhibited. It is typically left to the interventionists’ judgment to determine what is appropriate for each child; but in general, model prompts are more restrictive than open-ended questions. If open-ended questions (e.g., “What happened next?”) are sufficient to help the child continue storytelling or produce the linguistic target (e.g., causal subordination), then a model (e.g., “Say it like this, ‘He asked his mom for help because he needed a Band-Aid.’ ”) would be unnecessary.

In the preceding sections, we outlined how our primary concern is to help children who,for whatever reason, are having difficulty acquiring academically relevant language based on afunctional perspective. This perspective entails the idea that all children should receive the necessary services they require based on need, not based on any particular label. We proposed that narrative assessment and intervention can be effectively implemented in an RTI framework so that the academic success of all children can be promoted. Narrative assessment and intervention were highlighted as means of assessing and teaching literate, academically related language. Narrative assessment and intervention are functional and relevant to an entire student population and can be adapted for use in RTI systems.

In the preceding sections, we outlined how our primary concern is to help children who, for whatever reason, are having difficulty acquiring academically relevant language based on a functional perspective. This perspective entails the idea that all children should receive the necessary services they require based on need, not based on any particular label. We proposed that narrative assessment and intervention can be effectively implemented in an RTI framework so that the academic success of all children can be promoted. Narrative assessment and intervention were highlighted as means of assessing and teaching literate, academically related language. Narrative assessment and intervention are functional and relevant to an entire student population and can be adapted for use in RTI systems.

Case Examples of RTI for Language

Typically Developing Monolingual Students

David is 5 years old and is beginning kindergarten. He is from Nevada and his mother and father both speak English at home. David did not attend preschool. His parents believe that his

language is typically developing and that he is ready for kindergarten. After two weeks of school, David, along with all of the students in the school district, was administered a decoding-related universal benchmark screener. Additionally, all students were administered a brief universal benchmark screener of language using narrative assessment procedures. David’s narrative discourse was analyzed and met established criteria. His teacher then engaged the class in large group narrative intervention for 15 minutes, 3 days a week. David was involved in the large-group intervention procedures and appeared to be attentive and learning. At the end of 3 weeks of intervention, David was again administered a brief narrative assessment. His posttest scores increased and he met the criteria expected of students who have participated in large-group narrative intervention over 3 weeks. David was initially classified as not being at risk for language difficulty, and his language was monitored using brief universal benchmark language screenings using narrative assessment in January and then again in May. The results of the progress monitoring indicated adequate progress.

Typically Developing Students Who Are Culturally and Linguistically Diverse

Angela is David’s classmate. She is also 5 years old and is beginning kindergarten. She is from Mexico and has lived in the United States since she was 3 years old. Her parents speak Spanish at home. Angela attended one year of Head Start preschool and learned some English. She is Spanish language dominant both receptively and expressively. Her parents are uncertain whether she will succeed in a school where English is spoken in the classroom all the time. At the beginning of kindergarten, Angela began receiving services for English language learners from the school’s ELL teacher. After 2 weeks of kindergarten, Angela was administered a universal, benchmark English language screener using narrative assessment procedures. As expected from a static English language measure when administered to an ELL student, Angela scored very poorly. Angela then participated in explicit, large group English narrative intervention in her classroom with her general education teacher and appeared to be attentive and actively participating. At the end of 3 weeks of whole-class language intervention, Angela was readministered a narrative assessment. Her posttest scores increased considerably, suggesting that she is a typical language learner, but her scores were still below the expected range for English speaking children. Following the large-group narrative intervention, the narrative assessment results were reviewed to help inform treatment targets. Angela then participated in small group English narrative intervention sessions with the ELL teacher and with a paraprofessional each day for 3 weeks, with interprofessional collaboration that included modeling, coaching, and consultation from the SLP. During the small group sessions, Angela made considerable gains, providing greater evidence that she is a typical language learner who has limited English language proficiency. Her language was monitored using brief narrative assessments every month. She appears to be making adequate progress.

Students with Language Impairment

Jason is in the same class as David and Angela. He is almost 6 years old and is beginning kindergarten. He is from Nevada and his mother and father both speak English at home. Jason attended Head Start for two years and his parents and teachers have noted that he is struggling with understanding and using language. After 2 weeks of school, Jason was administered the universal language screener that used narrative assessment procedures. Jason scored in the very low range, significantly below the criteria established. Jason participated in narrative intervention for 15 minutes, 3 days a week across 3 weeks with his class. Jason was often distracted and was reticent to respond. At the end of 3 weeks of large-group intervention, Jason was again administered a narrative assessment. His scores slightly increased from his earlier narrative scores, but remained in the very low range. His limited response to the large-group instruction was concerning. Following the large-group narrative intervention, the narrative assessment results were reviewed to help inform treatment targets. Jason participated in tier 2, smallgroup narrative intervention sessions with a paraprofessional for 30 minutes per day for 3 weeks. The SLP, classroom teacher, and the paraprofessional collaborated frequently, and the SLP provided the necessary support and training. Jason made little progress in the tier 2 intervention. His lack of progress in the large-group and small-group settings were uncharacteristic of a typical language learner, and it was decided by those involved with Jason’s education that a more in-depth examination of his language ability should be undertaken. Functional aspects of Jason’s language were carefully assessed. The results of the comprehensive assessment aligned with the previous large-group and small-group dynamic assessment pretest-teaching-posttest results. His SLP determined that he has a language impairment. In addition to the large-group narrative intervention provided in his classroom, he began receiving individualized narrative instruction from the SLP for 30 minutes per day, 4 days per week. The SLP monitored his progress every two weeks using narrative retells and personal story elicitations. After 6 weeks it was clear that Jason was making progress, and that both his story retells and his generated personal stories were improving. Interprofessional collaboration continued with the school’s general educators, special educators, and literacy team.

Children with Language Impairment Who Are Culturally and Linguistically Diverse

Jose is 5 years old and is starting kindergarten with David, Angela, and Jason. His parents moved to the United States from Guatemala five months prior to his birth. Although Jose’s father speaks some limited English, his parents primarily speak Spanish at home. Jose did not attend preschool. As was the case with Angela, Jose began receiving services for English language learners from the school’s ELL teacher. After 2 weeks of school, Jose was administered an English universal narrative language screener. As expected, Jose performed very poorly on this static test. During his whole-class narrative intervention instruction, Jose had a difficult time understanding the directions and did not seem to be performing well. At the end of 3 weeks of large-group narrative intervention, Jose was again administered a narrative assessment. Jose was able to retell a limited story and showed some improvement, but his scores were still very low. Jose was then engaged in small group narrative intervention sessions for 30 minutes per day, 3 days per week. Jose’s progress in the small group sessions was very limited. His limited response to the large-group and small-group narrative intervention indicated that he may have unusual difficulty learning language. He was referred for a comprehensive evaluation of his language. Jose received a battery of assessments in English and Spanish that focused on functional aspects of language. The SLP also administered a dynamic assessment of language and a non-word repetition processing-dependent task. After reviewing Jose’s response to the large-group and small-group narrative interventions, and after considering the results of the assessments administered by the SLP and consulting with Jose’s parents, his general education teacher, the ELL teacher, and others who were familiar with Jose’s language and academic performance, it was determined that he most likely has a language impairment. Jose began receiving individualized instruction for 30 minutes per day, 2 days per week. His progress was monitored during each intervention session and by eliciting narrative retells and personal generations every 2 weeks. After 4 weeks, the SLP noted that Jose was making very little progress. The SLP then increased the intensity of his individualized narrative intervention

sessions to 30 minutes per day, 4 days per week. Jose’s progress was again monitored frequently and the results indicated significant growth. Interprofessional collaboration was fostered with the

school’s general educators, special educators, and the literacy team.

Summary

Language-related difficulty is likely driving the discrepant results in reading performance for culturally and linguistically diverse children. Most of these children do not have language impairment; nevertheless, they do need explicit instruction in the use and comprehension of complex literate language that is expected in public schools. SLPs have the appropriate education and scope of practice to help guide this needed explicit language instruction and language progress monitoring. We suggest that it should become standard practice in schools to monitor language growth and provide explicit language instruction to students and that a multi-tiered framework offers several advantages to the organization of such instruction. By clearly defining the problem many of our children face in school today — language-related difficulty — we can potentially make significant improvements in reading performance for all children, including those who are culturally and linguistically diverse.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Teresa Ukrainetz for her constructive feedback and Alexandra Costello for her valuable service.

References

American Speech-Language Hearing Association. (2010). Roles and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists in schools [Position Statement]. Available from www.asha.org/policy American Speech-Language Hearing Association. (2013). Interprofessional Education: Why is greater emphasis being placed on interprofessional education in health care? What impact will it have on the education of audiologists and speech-language pathologists? Retrieved December 13, 2013 from http://www.asha.org/academic/questions/interprofessional-Education/

Aram, D. M., & Hall, N. E. (1989). Longitudinal follow-up of children with preschool communication

disorders: Treatment implications. School Psychology Review, 18(4), 487–501.

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Efficient and effective teaching. New York, NY: The

Guilford Press.

Bauman, R. (1986). Story, performance, and event: Contextual studies of oral narrative (Vol. 10). Cambridge

University Press.

Brown, C., & Petersen, D. B. (2010). The Effects of Narrative Intervention on a Child with Autism. Poster

presented at the American Speech, Language Hearing (ASHA) Convention. Philadelphia, PA.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Tomblin, J. B., & Zhang, X. (2002). A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes

in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 45(6),

1142–1158.

Deno, S. L. (2003). Developments in curriculum-based measurement. Journal of Special Education, 37(3),

184–192.

Deno, S. L., Mirkin, P. K., & Chiang, B. (1982). Identifying valid measures of reading. Exceptional Children,

49(1), 36–45.

Dickinson, D. K., & McCabe, A. (2001). Bringing it all together: The multiple origins, skills, and

environmental supports of early literacy. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 16(4), 186–202.

Eisenberg, S., Ukrainetz, T., Hsu, J., Kaderavek, J., Justice, L., & Gillam, R. (2008). Noun phrase

elaboration in children’s spoken stories. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39, 145–157.

Feuerstein, R. (1980). Instrumental Enrichment: An Intervention Program for Cognitive Modifiability.

Baltimore: University Park Press.

Fey, M. E. (1986). Language intervention with young children. San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press.

Francis, D. J., Rivera, M., Lesaux, N., Kieffer, M., & Rivera, H. (2006). Practical guidelines for the education of

English language learners: Research-based recommendations for instruction and academic interventions.

Center on Instruction.

Greenhalgh, K. S., & Strong, C. J. (2001a). Literate language features in spoken narratives of children with

typical language and children with language impairments. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in

Schools, 32(2), 114–125.

Griffin, T. M., Hemphill, L., Camp, L., & Wolf, D. P. (2004). Oral discourse in the preschool years and later

literacy skills. First Language, 24(2), 123–147.

Grigorenko, E. L. (2009). Dynamic assessment and response to intervention: Two sides of one coin. Journal

of Learning Disabilities, 42(2), 111–132.

Gillam, S. L., Gillam, R. B., & Reece, K. (2012). Language outcomes of contextualized and decontextualized

language intervention: Results of an early efficacy study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools,

43, 276–291.

Gillam, R. B., & Johnston, J. R. (1992). Spoken and written language relationships in language/learning

impaired and normally achieving school-age children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35,

1303–1315.

Gillam, S., & Olszewski, A. (2010). Classroom-Based Narrative Intervention for Diverse Learners, Session

number 1074, American Speech-Language Hearing Association Convention, Philadelphia, PA.

Gillam, S., Olszewski, A., & Segura, H. (2011). Measuring Narrative Language Growth in Multiple Contexts.

Symposium on Research in Child Language Disorders, Madison, WI.

Gillam, R. B., & Pearson, N. (2004). Test of Narrative Language. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Greenhalgh, K. S., & Strong, C. J. (2001b). Literate language features in spoken narratives of children with

typical language and children with language impairments. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in

Schools, 32, 114–125.

Gutierrez-Clellen, V. F., & Peña, E. (2001). Dynamic assessment of diverse children: A tutorial. Language,

Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 212–224.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American

children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Hayward, D., & Schneider, P. (2000). Effectiveness of teaching story grammar knowledge to pre-school

children with language impairment. An exploratory study. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 16(3),

255–284.

Haynes, W. O., & Pindzola, R. H. (2012). Diagnosis and Evaluation in Speech Pathology (8th ed.). Pearson/

Allyn & Bacon. Boston, MA.

Heilmann, J., Miller, J. F., Iglesias, A., Fabiano-Smith, L., Nockerts, A., & Digney Andriacchi, K. (2008).

Narrative transcription accuracy and reliability in two languages. Topics in Language Disorders, 28(2),

178–188.

Heilmann, J., Nockerts, A., & Miller, J. F. (2010). Language sampling: Does the length of the transcript

matter? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 393–404.

Heward, W. L. (1996). Three low-tech strategies for increasing the frequency of active student response

during group instruction. In R. Gardner, III, D. M. Sainato, J. O. Cooper, T. E. Heron, W. L. Heward,

T. A Eshleman, J. W., Grossi (Eds.), Behavior analysis in education: Focus on measurably superior instruction

(pp. 283–320). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. Pub. L. No. 108-446. (2004). Retrieved

from http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/%2Croot%2Cstatute%2C

Jenkins, J. R., Hudson, R. F., & Johnson, E. S. (2007). Screening for service delivery in an RTI framework:

Candidate measures. School Psychology Review, 36, 560–582.

Johnson, C. J., Beitchman, J. H., Young, A., Escobar, M., Atkinson, L., Wilson, B., … Wang, M. (1999).

Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech/language impairments: Speech/language

stability and outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 42(3), 744–760.

Jones, M. D. (1998). The thinker’s toolkit: Fourteen powerful techniques for problem solving. New York: Times

Business.

Kamhi, A. (2007). Knowledge deficits: The true crisis in education. The ASHA Leader, 12(7), 28–29.

Kamhi, A. (2009a). Prologue: The case for the narrow view of reading. Language, Speech, and Hearing

Services in Schools, 40, 174–178.

Kamhi, A. (2009b). Epilogue: Solving the reading crisis – take 2: The case for differentiated assessment.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 212–215.

Leonard, L. B. (1987). Is specific language impairment a useful construct? In S. Rosenberg (Ed.) Advances in

psycholinguistics: Volume I: Disorders of first language development (pp. 1–39). New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns (No. 4). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Marston, D. (2005) Tiers of intervention in responsiveness to intervention: Prevention outcomes and learning

disabilities identification patterns. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(6), 539–544.

Mayer, M. (1969). Frog, where are you? New York: Dial Press.

McCabe, A. (1991). Structure as a way of understanding. In A. McCabe & C. Peterson (Eds.), Developing

narrative structure (pp. ix–xvii). Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

McGregor, K. K. (2000). The development and enhancement of narrative skills in a preschool classroom:

Towards a solution to clinician-client mismatch. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9(1), 55.

Missall, K. N., & McConnell, S. R. (2004). Psychometric characteristics of individual growth & development

indicators: picture naming, rhyming, and alliteration.

Moffett, J. (1968). Teaching the universe of discourse. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

NAEP Assessment Tool. (2011). Figure 8. Retrieved October 1, 2013, from http://nationsreportcard.gov/

reading_2011/reading_2011_report/pages/graphs/fig_8.asp

Nakamoto, J., Lindsey, K. A., & Manis, F. R. (2007). A Longitudinal analysis of English Language learners

word decoding and reading comprehension. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 20, 691–719.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center), & Council of Chief State School

Officers (CCSSO). (2010). Common Core State Standards. Washington D.C.

Nelson, K. (1991). Remembering and telling: A developmental story. Journal of Narrative & Life History.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2005). Pathways to reading: The role of oral language in the

transition to reading. Developmental Psychology, 41(2), 428–442.

Nippold, M. A. (1998). Later language development: The school-age and adolescent years (2nd ed.). Austin,

TX: Pro-Ed.

Nippold, M. A., & Taylor, C. L. (1995). Idiom understanding in youth: Further examination of familiarity and

transparency. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 38(2), 426–433.

Nippold, M. A., Ward-Lonergan, J. M., & Fanning, J. L. (2005). Persuasive writing in children, adolescents,

and adults: A study of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic development. Language, Speech and Hearing

Services in Schools, 36(2), 125–138.

Pence, K., Justice, L. M., & Gosse, C. (2007). Narrative Assessment Protocol. Preschool Language & Literacy

Lab, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

Petersen, D. B., De George, C., Zebre, J., Ukrainetz, T. A., & Spencer, T. D. (2011). The Effects of Narrative

Intervention on the Language Production of Children with Autism. Symposium presented at the 37th Annual

Association for Behavior Analysis International Conference. Denver, CO.

Petersen, D. B. (2011). A systematic review of narrative-based language intervention with children who have

language impairment. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(4), 207–220.

Petersen, D. B., & Gillam, R. B. (in press). Predicting reading ability for bilingual Latino children using

dynamic assessment. Journal of Learning Disabilities.

Petersen, D. B., Gillam, S. L., Spencer, T., & Gillam, R. B. (2010). The effects of literate narrative

intervention on children with neurologically based language impairments: an early stage study. Journal of

Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 53(4), 961.

Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012a). The Narrative Language Measures: Tools for language screening,

progress monitoring, and intervention planning. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 19(4),

119–129.

Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012b). The narrative language measures: Tools for language screening,

progress monitoring, and intervention planning. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 19(4),

119–129.

Pettipiece, J., & Petersen, D. B. (2013, October). Inter-rater reliability of scoring procedures of bilingual

children’s narratives. Poster presented at the 4th Intermountain Area Speech and Hearing Convention,

Denver, CO.

Saleebey, D. (1994). Culture, theory, and narrative: The intersection of meanings in practice. Social work,

39(4), 351–359.

Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., & Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in

classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Education and Treatment of Children, 1(3),

351–380.

Shawhan, M., & Petersen, D. B. (2013). Effects of length and context in narratives for bilingual children.

Poster presented at the 4th Intermountain Area Speech and Hearing Convention. Denver CO, October.

Shaywitz, S. E., Escobar, M. D., Shaywitz, B. A., Fletcher, J. M., & Makuch, R. (1992). Evidence that

dyslexia may represent the lower tail of the normal distribution of reading ability. New England Journal of

Medicine, 326, 145–150.

Snow, C. E., Porche, M. V., Tabors, P. O., & Harris, S. R. (2007). Is literacy enough? Baltimore, MD: Brookes

Publishing Co.

Snowling, M., & Hulme, C. (1989). A longitudinal case study of developmental phonological dyslexia.

Cognitive Neuropsychology, 6(4), 379–401.

Spencer, T. D., Kajian, M., Petersen, D. B., & Bilyk, N.. (in press). Effects of an individualized narrative

intervention on children’s storytelling and comprehension skills. Journal of Early Intervention.

Spencer, T. D., Petersen, D. B., Slocum, T. A., & Allen, M. M. (in press). Large group narrative intervention in

Head Start preschools: Implications for response to intervention. Journal of Early Childhood Research.

Spencer, T. D., & Slocum, T. A. (2010). The effect of a narrative intervention on story retelling and personal

story generation skills of preschoolers with risk factors and narrative language delays. Journal of Early

Intervention, 32(3), 178–199.

Stothard, S. E., Snowling, M. J., Bishop, D. V. M., Chipchase, B. B., & Kaplan, C. A. (1998). Languageimpaired preschoolers: A follow up into adolescence. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research,

41(2), 407–419.

Strong, C. J., & Shaver, J. P. (1991). Stability of cohesion in the spoken narratives of language-impaired and

normally developing school-aged children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 34(1), 95.

Tilstra, J., & McMaster, K. (2007, ). Productivity, fluency, and grammaticality measures from narratives

[Electronic version]. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 29(1), 43–53.

Tomblin, J. B., Records, N., Buckwalter, P., Zhang, X., Smith, E., & O’Brien, M. (1997). Prevalence of

specific language impairment in kindergarten children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research,

40, 1245–1260.

Ukrainetz, T. A., Justice, L. M., Kaderavek, J. N., Eisenberg, S. L., Gillam, R. B., & Harm, H. H. (2005). The

development of expressive elaboration in fictional narratives. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing

Research, 48, 1363–1377.

Ukrainetz, T. A. (2006a). The implications of RTI and EBP for SLPs: Commentary on L. M. Justice.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 298–303.

Ukrainetz, T. A. (2006b). Contextualized Language Intervention: Scaffolding Pre-K-12 Literacy Achievement.

Eau Claire, WI: Thinking Publications.

Ukrainetz, T. A., & Gillam, R. B. (2009). The expressive elaboration of imaginative narratives by children

with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 883–898.

Weddle, S., Kajian, M., Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (May, 2013). Promoting Generalized Use and

Maintenance of Autoclitics During Storytelling. Poster presented at the 39th Annual Association for Behavior

Analysis International Conference, Minneapolis, MN.

Weddle, S., Zitting, L., & Spencer, T. D. (Oct., 2013). Tiered language intervention in Head Start preschools:

An efficacy and implementation study. Poster presented at the Arizona Association of School Psychologists.

Phoenix, AZ.

Westby, C. E. (1985). Learning to talk—talking to learn: Oral literate language differences. In C. Simon (Ed.),

Communication skills and classroom success: Therapy methodologies for language-learning disabled students

(pp. 181–213). San Diego, CA: College-Hill.

Westby, C. E. (1999). Assessing and facilitating text comprehension problems. Language and Reading

Disabilities, 2, 157–232.