Teachers and teaching assistants from three Head Start classrooms implemented a multitiered narrative intervention in their preschool classrooms. They delivered large group, small group, and individual lessons with students and administered and scored a progress monitoring tool with all children once a month. A quasi-experimental control group design was conducted to determine the effect of the multi-tiered intervention on children’s story retelling skills and story-based language comprehension. The extent to which the Head Start teachers’ could deliver the intervention with fidelity and administer and score the progress monitoring probes accurately were examined. Feasibility data were collected via interviews and questionnaires. Results indicated statistically significant improvements favoring the treatment group at Winter and Spring assessment points for story retelling and language comprehension. All measures of teachers’ fidelity and reliability were above acceptable standards. As teachers and teaching assistants became more comfortable delivering the intervention, teachers’ perceptions of the intervention’s feasibility increased.

Keywords: language intervention, implementation, narratives

Although reading comprehension is clearly important—it is the reason why students learn to read—it has been largely ignored in preschool and early elementary grades. The focus in the early years instead has been on narrowly defined skills such as phonemic awareness, concepts of print, and alphabetic knowledge (Dooley & Matthews, 2009). There appears to be a patent contradiction between what is most valued in school and what is taught. There is, however, promise and validation in noting that students learn what teachers focus on in their instruction. Decoding is a perfect case in point. Because decoding-related skills have been primarily emphasized in the early school years, very few students struggle with word-level reading and reading fluency (Nakamoto, Lindsey, & Manis, 2007). Conversely, reading comprehension has not been a major focus of teacher instruction, and thus predictably, reading assessments consistently indicate that the vast majority of students across the U.S. do not meet grade-level expectations for reading comprehension (e.g., National Center for Education Statistics, 2015).

Young children with risk factors such as low income face unique challenges with respect to comprehension development. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds on average, perform lower than peers from more advantaged backgrounds on reading comprehension tasks. In fact, approximately 80% of culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse students read below grade level when reading comprehension tests are used to measure reading achievement (National Center for Education Statistics, 2015). Comprehension should be targeted early (McNamara & Kendeou, 2011), yet teachers have not addressed reading comprehension in the younger grades, especially in preschool and kindergarten, for one glaringly obvious reason— young students do not yet know how to read. Teaching them to comprehend text that they cannot access is not possible. Fortunately, reading comprehension has an oral language complement, and oral language can be addressed at very early ages before children can read.

There is mounting evidence that indicates that when teachers engage in oral language instruction, children learn what is taught (Gettinger & Stoiber, 2008; Justice et al., 2009; PollardDurodola et al., 2011). These oral language activities are suitable for building comprehension in preschool, and the more the oral language instruction focuses on language that is reflective of written language, the more likely oral language skills will transfer to reading comprehension. Narrative language (storytelling), in particular, can help bridge the gap between oral and written language. Narratives often contain the same level of language complexity as written language. Thus, through narrative-based language intervention, teachers can help young children learn to comprehend language that is similar in complexity to the written language they will need to decode and comprehend in later grades.

Because the majority of students in the U.S. perform poorly on reading comprehension assessments, the responsibility of teaching reading comprehension falls not only on special education, but also on general education. Those students who do not make adequate progress in the classroom, or who are identified as having a disorder, will need more intensive, differentiated instruction. Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) is a promising approach to differentiated instruction that is trickling into early childhood education (Buysse & Peisner-Feinberg, 2013). In fact, the National Head Start Association jointly prepared a position statement about tiered frameworks in early childhood education with the National Association for the Education of Young Children, the Division of Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children, and the National Head Start Association (2013). The joint position statement provides direction to early childhood professionals about the assessment recommendations and the need for tiered supports to promote achievement for all children.

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

Tiered systems are designed and implemented in a school-wide fashion to make prevention, rather than remediation, possible for students of various ability levels (Greenwood & Kim, 2012). Within an MTSS framework, all children are initially assessed via universal screening and identified as either being on target for academic expectations or being in need of more intensive instruction in a given area. All students are then assigned to different tiers of instruction according to their specific needs. Tier 1 instruction typically takes place in the general classroom setting, and all students in that tier are provided a similar intensity of instruction, with few individualized supports or scaffolding. According to research implemented in elementary schools, approximately 80% of students respond sufficiently to tier 1 instruction (Mellard, McKnight, & Jordan, 2010). However, this does not appear to be the case with Head Start preschoolers—at least not in the domain of language. Spencer, Petersen and Adams (2015) found that over 50% of students in Head Start classrooms scored below the benchmark for language. They recommended that those students receive small group, targeted oral language intervention. Such interventions can be considered Tier 2 or secondary supports. These students participate in both Tier 1 instruction and Tier 2 intervention, and their progress is regularly monitored. There are still some students who do not make adequate progress even when given Tier 1 and Tier 2 support. These students are assigned to the third and highest level of intensive support, Tier 3. Tier 3 is often a preliminary step to special education, or equivalent to special education, depending on the MTSS model (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2005). Only a few students in each class should need this level of support. Importantly, MTSS requires reliable and valid assessments that are easy to use and can be repeated over time to assess progress (Deno, 2003). Students’ responsiveness in their respective tiers of instruction is monitored and data are used to make educational decisions pertaining to the intensity of instruction.

MULTI-TIERED NARRATIVE INTERVENTION

Story Champs (Spencer & Petersen, 2012a), the narrative intervention curriculum examined in this study, was designed specifically for multi-tiered implementation for preschool and schoolage children. Some studies have examined the impact of Story Champs on outcomes of schoolage students (Petersen, Brown, Ukrainetz, DeGeorge, Spencer, & Zebre, 2014; Petersen, Thompson, Guiberson, & Spencer, 2015; Gardner, Spencer, & Petersen, 2015), but much of the research and development has occurred in Head Start preschool classrooms, where the needs for language promotion are high (Spencer et al., 2015). The validity and reliability of a curriculum based measurement tool for language and comprehension (i.e., Narrative Language Measures) have also been examined in previous research (Petersen & Spencer, 2012). The current study represents the first attempt to integrate all of the intervention and assessment components to form a multi-tiered system of language support in Head Start preschool classrooms. In the remainder of this section, we provide an overview of Story Champs, the Narrative Language Measures, and then describe each study that preceded the current study.

The active ingredients of Story Champs include carefully constructed, personally-themed stories and explicit teaching procedures based on the effective teaching literature. Twelve stories serve as the basis for instruction, all of which reflect themes that are commonly experienced by young children (e.g., getting hurt, misplacing something, wanting something someone else has). The stories were designed with intentional structures so that they can be targeted during intervention. Each story is 68-70 words long and contains the same story grammar structures based on the Stein and Glenn (1979) framework: character, setting, problem (initiating event), feeling (internal response), action (attempt), and ending (consequence). In addition, each story was constructed with the same linguistic features. They each have two causal subordinate clauses using the word because, one temporal subordinate clause using the words after or when, one temporal tie using the word then, one instance of dialogue, two adjectives, and one adverb. These story and linguistic structures align with the developmental expectations of typical preschool/kindergarten children and accepted academic standards (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010; Teaching Strategies, Inc., 2010).

In all three tiers of Story Champs, the teacher models the stories and then supports the children to tell and retell stories. Storytelling and/or the language used to tell the stories are targeted in intervention, depending on the child’s language skills; however, the purpose of the program is not to memorize or learn the stories themselves. Multiple exemplar training across the twelve stories is used to reveal the pattern of stories (i.e., story structure) and encourage the use of more complex, academically-related language in the context of storytelling (i.e., linguistic structure). The goal is to use the Story Champs stories to teach the acquisition of story and linguistic structures that generalize to other language contexts such personal storytelling under natural conditions and comprehending and retelling books that teachers read aloud. Although Story Champs is a three-tiered curriculum, the possible arrangements—large group, small group, and individual—do not necessarily align with Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 of MTSS. For example, in one center, large group Story Champs instruction may constitute a Tier 2 intervention. Likewise, a Tier 3 intervention may be delivered to small groups instead of only one child at a time.

With respect to explicit teaching procedures, there is a specified set of strategies embedded in the Story Champs curriculum based on explicit preschool teaching principles that are informed by behavioral science, developmental theory, and empirical evidence that clearly connect early language development and literacy (Archer & Hughes, 2011; Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomlin, 2001; Justice, Mashbrun, Hamre, & Pianta, 2007; Lonigan, 2006; Storch & Whitehurst, 2002). Young children who enter kindergarten with strong language skills find greater academic success than those children who have difficulty with language-related tasks in preschool (Chaney, 1998; Gallagher, Frith, & Snowling, 2000; Justice et al., 2007; Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000; O’Connor & Jenkins, 1999). As outlined by Justice et al., 2007, high quality literacy instruction in preschool is centered around contextualized, purposeful, explicit, systematic language-related instruction, where the teacher often engages students in conversation, with students having frequent opportunities to talk, the repeated use of open-ended questions, expansion and recasting of student responses, and modeling of complex, academic language. Story Champs integrates these evidence-based, high-quality language and literacy instructional practices into a semi-manualized curriculum. These teaching procedures are centered around multiple stories that children are expected to retell with appropriate story grammar structure and language complexity.

To facilitate the teaching of the structures in the stories, a five-panel set of illustrations accompany each story and a set of story grammar icons are used to help make each part more concrete. Master lesson plans (or procedural checklists) outline the required steps for implementation at each tier. Because the master lesson plans do not contain scripts, we consider the program to be manualized, but flexible. The steps are required, but how each step is delivered depends on the skill, creativity of the teacher, and the needs of the children. Although the steps differ slightly between large group, small group, and individual implementation (e.g., structured based on group size and opportunities to respond), the overarching principle is that visual materials (illustrations and icons) are faded while the demand for more independent storytelling increases. The process of prompt fading is gradual and systematic so that children can be successful. The visuals are removed within session to ensure children do not become dependent on them. Simple responding games are used to encourage children to be actively engaged while they listen to a peer retell the story.

During the development of Story Champs, a companion assessment tool was also developed so that data-based decisions could be made for the identification of children for more intensive tiers and their progress can be monitored related to those interventions. The Narrative Language Measures (NLM) for preschoolers (Spencer & Petersen, 2012b) involves three types of narrative tasks. The primary task is retelling, whereas, generating personal stories and answering questions about stories serve as secondary tasks. There are 25 parallel stories used in the administration of the NLM for preschoolers, with each story comprising a separate form for repeated administration over time. Stories were constructed using the same story and linguistic structures as the Story Champs stories. Importantly, the NLM stories are not used in Story Champs so that they are unfamiliar to children during assessment. To administer the retell task, an examiner or teacher reads a short introductory script, reads a story, and then asks the child to retell the story (see sample in appendix). Scoring can be done in real time or audio recorded for later scoring. If the personal generation task is administered, the examiner or teacher tells one of the parallel stories as if it is his/her own experience and asks the child if something like that has ever happened to him/her. It is more difficult to score personal stories in real time, so the child’s story is audio recorded and scored later. After the child retells the story, the examiner or teacher may choose to ask a set of five story structure questions.

Large group Story Champs. Spencer, Petersen, Slocum, and Allen (2014) completed a quasi-experimental control group study with four Head Start classes and with 71 preschoolers who were culturally and linguistically diverse. Author served as the interventionist because this was the first attempt to deliver narrative intervention to a large group up to 20 children at a time. She conducted 12 sessions over three weeks each lasting approximately 15-20 minutes. Some features that are unique to the large group procedures include an exclusive focus on retelling skills, choral responding to help all the children produce parts of the story, and a peer-tutoring component in which every child retold the modeled story to a classmate. Each participant’s retell, personal generation, and question answering skills were assessed at preintervention, post-intervention, and at a 4-week follow up. Results indicated that the treatment group’s retell (p = .046, d = 0.49) and question answering (p = .023, d = 0.56) scores were statistically significantly higher than the control groups at post-intervention and follow-up but the intervention had a minimal impact on children’s personal generation skills. Importantly, this pattern of results was consistent for the subgroup of children who were English language learners (55% of total group) as well as the group as a whole.

Small group Story Champs. In the first study of small group Story Champs (Spencer & Slocum, 2010), participants included five diverse preschoolers enrolled in Head Start who had limited language skills. Using multiple baseline across groups experimental design, the five participants were distributed among three small groups of four students. Authors served as interventionists and only focused on teaching story grammar. The teaching procedures ensured children received practice in both retell and personal generation tasks. Icons and illustrations were systematically faded to encourage more independent retelling and storytelling and games were used to enhance active listening and motivation. Intervention was delivered four days a week for 7-18 minutes. Based on visual analyses of graphs, all five preschoolers retold more complete stories following intervention, and improvements in personal stories were also noted for most of the participants. The researchers noted the potential for differentiated intervention, although not attempted in their study, because each participant presented with diverse needs (e.g., vocabulary, story grammar, lengthening utterance, use of subordination).

In a follow up study (Spencer et al., 2015), the small group format was investigated again with children with limited language skills attending Head Start. However, this time differentiation was built into the procedures so that each child could receive support that matched their language needs. Using participants’ NLM-Retell results, interventionists identified story grammar and linguistic components that were missing from their retells and selected targets for intervention in a flexible ongoing manner. During sessions, a single interventionist delivered Story Champs to four children while prompting their use of individualized targets. Interventionists followed the master lesson plan steps, but tailored his/her prompting to the needs of the children. For example, one child in the group worked on temporal and causal subordination, another child was encouraged to use longer sentences, another child was working on telling complete stories with all the story grammar components, and the last child was encouraged to use English verbs. Participants received intervention twice a week for 15-20 minutes a day for nine weeks. Using a randomized group design, the treatment children showed statistically significant improvements over the control group on the NLM-Retell task (p = .02, d = 1.05) and a distal norm-referenced narrative assessment (p = .014, d = 1.04), but not on the personal generation task. A bilingual speech-language pathologist and two psychology students served as interventionists instead of the researchers themselves.

Individual Story Champs. To examine the individual or Tier 3 arrangement in Head Start classrooms, Spencer, Kajian, Petersen, and Bilyk (2014) conducted a multiple baseline, multiple probe study with five preschoolers with developmental disabilities, four of whom were Spanish-speaking English learners. Each child received 24 sessions of Story Champs, each lasting 10 to 15 minutes, twice a week. Individual intervention procedures are similar to the small group procedures in that both retell and personal stories are addressed and the illustrations and icons are faded within session. The unique feature, however, is the use of pictography (McFadden, 1998). After the child retold the model story, with and without the support of illustrations and icons, the child told a personal story. The interventionist used stick notes to draw each part of the child’s story (i.e., character, problem, feeling, action, ending). The child used the sticky note drawings to retell his/her own personal story. Because the children had fewer oral language skills than participants in the other studies, one of the primary measures was the answering questions task of the NLM. In addition, children were allowed to look at pictures when the examiner read the NLM story and when they retold the stories. All children showed meaningful improvements on story retells with and without pictures present, answering questions, and personal stories.

Implementation Variables

Invested policy makers and administrators encourage practitioners to select interventions with sufficient empirical support. Unfortunately, equal attention is not given to the evidence of successful implementation of those interventions and the conditions in which quality implementation and positive student outcomes are achieved (Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). Although it is important to disseminate interventions with strong evidence of efficacy, it is equally important to ensure that empirically supported interventions are usable, feasible, and effective when delivered in the real world, by practicing teachers.

Implementation science researchers have recommended that questions pertaining to the application of research should be addressed even in early stage intervention research and development. Werner (2004) suggested that by examining implementation variables in the early stages of intervention research, developers gain insight into the culture of real world settings and receive rapid feedback about what works and what doesn’t work during the formative period of the intervention. When end users serve as intervention agents, for example, researchers become aware of barriers to implementation that may not have been detected if researchers had delivered the intervention. Early detection of barriers and obstacles to implementation allow researchers to revise and refine an intervention before it advances through the phases of research to more costly large-scale efficacy studies (Fey, Finestack, & Schwartz, 2009; Odom, et al., 2005). Efficacy research coupled with implementation science can inform the development and sustainability of interventions and lead to better outcomes for children (Durlak & DuPre, 2008).

There are important implementation variables to consider during early phases of intervention research, including characteristics of the intervention, the individuals who implement it, and the context in which the intervention is implemented (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). For example, the extent to which an intervention matches the values embedded in the intended setting may determine how well the intervention is adopted and sustained (Harn, Parisi, & Stoolmiller, 2013). An intervention must also be able to fit with the other necessary activities of that setting. The transportability of an intervention to different settings should not be assumed because it has been examined in a similar, but different setting. This is especially true for Head Start classrooms that differ from district sponsored or private preschools in terms of the required daily activities (e.g., meals, teeth brushing), the qualifications of teachers, and the population they serve. When designing new interventions for Head Start implementation, questions of efficacy and implementation are paramount.

SUMMARY AND CURRENT STUDY

The purpose of the current study was twofold. First, we investigated the efficacy of a new, author-developed, commercially available multi-tiered oral language curriculum designed to improve language comprehension and ultimately, although not measured, reading comprehension. Under relatively typical conditions in Head Start classrooms, teachers and teaching assistants delivered all interventions and administered progress monitoring probes across the year. Research staff provided initial training, modeling, and coaching. The second purpose was to investigate aspects of implementation to ascertain the extent to which a multitiered system of language support was feasible for Head Start teachers and teaching assistants to use effectively. Specifically, fidelity of intervention implementation was observed regularly, fidelity of administering the progress monitoring probes was evaluated, and reliability of scoring was measured. In addition to the fidelity and reliability measures, teachers and teaching assistants completed an implementation feasibility questionnaire at regular time points across the year to document their self-efficacy with the interventions and assessments, the level of support they received and/or needed to implement the program, the ease and time efficiency of the program, and the students’ engagement during the intervention.

In the four studies reported above, researchers and research assistants administered and scored the NLM. The fidelity of NLM administration was documented alongside scoring reliability. Results indicated that the researchers and research assistants were able to administer the NLM with mean fidelity of 95% and score it with high agreement (mean=93%). Although psychometric data indicate that the NLM has excellent evidence of validity and reliability, much of those data are based on researcher administration. More information is needed on the feasibility of using the NLM in the natural setting with end users (i.e., Head Start teachers).

In all the studies above, the intervention was examined under researcher-influenced conditions. All of the sessions took place in Head Start classrooms, but the researchers or research assistants provided the interventions, which adds personnel and resources to the implementation. Fidelity of Story Champs implementation, consisting primarily of adherence to procedural steps and quality, was documented for all four studies, with a mean fidelity of 98.3% across the studies. Although this might suggest the intervention is easy to use, all that is clear is that it was easy for the researchers and their research assistants to use, who do not represent the end users. In all of the studies, Head Start teachers were asked to complete a short 5 or 6 item questionnaire to elicit their thoughts about the feasibility and potential of Story Champs in their classrooms. The questionnaires included items about the ease of Story Champs to learn, how well the students seemed to enjoy the lessons, whether the teachers thought the program was developmentally appropriate, and how interested they were in using the program. Responses were recorded in a Likert scale from 0-5. The mean score across the four studies was 4.7 (range 3.7-5.0), suggesting that the teachers perceived Story Champs to be highly appropriate and feasible in their classrooms. To fully implement an integrated multi-tiered system of language support, the implementation of a multi-tiered intervention with end users needs to be examined.

Although the measurement of implementation fidelity and teachers’ perceptions were reasonable given that these studies represent early development and design studies (Collins, Joseph, & Bielaczyc, 2004), the logical next step is to investigate the multi-tiered narrative intervention under more natural conditions with Head Start teachers and teaching assistants delivering the lessons. It will be important to know if after implementing the program, Head Start teachers remain as optimistic about Story Champs. Furthermore, it will be important to examine whether fidelity of administration and reliability of the NLM can still reach acceptable levels when examiners other than researchers administer the assessment.

Five specific research questions addressed the two-fold purpose of investigating the efficacy of Story Champs and the feasibility of Story Champs and the NLM in Head Start preschool classrooms.

- To what extent does a multi-tiered narrative intervention improve student’s narrative language and language comprehension skills when it is implemented by Head Start teachers and teaching assistants?

- To what extent do Head Start teachers and teaching assistants implement multi-tiered narrative intervention with fidelity?

- To what extent do Head Start teachers and teaching assistants administer a narrative retell assessment with fidelity? 4. To what extent do Head Start teachers and teaching assistants score a narrative retell assessment with reliability?

- To what extent do Head Start teachers and teaching assistants perceive multi-tiered narrative intervention and assessment to be feasible and do their perceptions improve with time?

METHOD

Participants and Setting

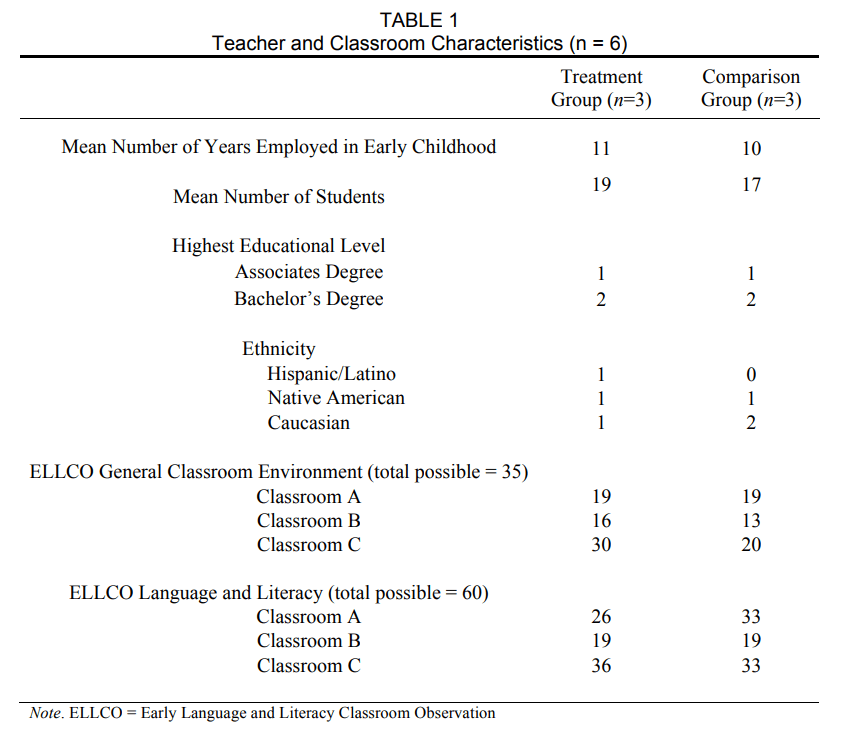

This research took place in a southwest state in a mid-size city. Researchers invited three teachers from three different Head Start centers to participate in the study and to implement the multi-tiered system in their classrooms. All three sets of teachers accepted the invitation and completed a brief demographic survey asking about their teaching experience, their education, and the number of children in the classroom. In two of the classrooms, teaching assistants also helped implement the multi-tiered intervention and conduct assessments, but they did not complete the demographic survey. Three other teachers from three different Head Start centers were invited to serve as control classrooms. Two half-day classrooms and one extended day classroom were represented in both conditions. At the beginning of the year, the research team conducted observations of each classroom using the Early Language & Literacy Classroom Observation (ELLCO; Smith, Brady, & Anastasopoulos, 2008). The ELLCO is a measure of classroom environment quality and includes items related to classroom structure, curriculum, language environment, books and book reading, and print and early writing. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, where five represents exemplary and one represents deficient. It yields two subscales: General Classroom Environment and Language and Literacy. Scores closer to the total possible indicate higher quality than those further from the total. Table 1 displays the teacher and classroom characteristics of each condition. With the exception of Classroom C and its comparison classroom on General Classroom Environment, the groups received similar ELLCO ratings.

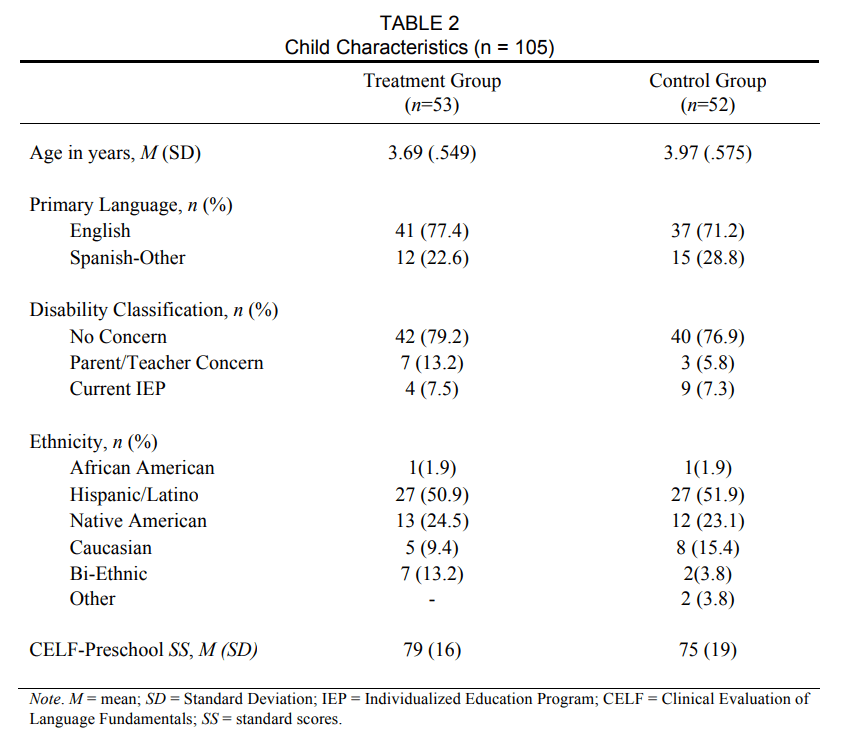

All research activities, including the data collection performed by the research team, took place in the preschool classrooms. Teacher and teaching assistant teams completed all intervention sessions and the progress monitoring assessments. The person responsible for each activity of the MTSS implementation differed in all three classrooms. In classroom A (full day), the teacher delivered large group lessons and administered the NLM-Retell task while one assistant delivered the small group lessons, and the other assistant delivered the individual lessons. In classroom B, the teacher delivered the large group lessons and the teaching assistant delivered the small group and individual lessons and conducted the progress monitoring probes using the NLM. In classroom C, the teacher completed all of the lessons and assessments herself. Child participants included 105 children attending preschool in the classrooms of the teachers who were recruited to participate in the study. Children ranged from three years, one month to five years, one month at the beginning of the study. When parent permission was obtained, parents completed a demographic survey to document children’s ethnicity, primary language, and whether there were developmental concerns. All children were administered the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – Preschool (CELF-P; Wiig, Secord, & Semel, 2004) to describe their language skills at the onset of the study. Child Characteristics are detailed in Table 2.

Research Design and General Procedures

To answer research question one, a quasi-experimental, control group design was conducted. In line with MTSS models, outcome data were collected seasonally (fall, winter, spring) on all the children in the six classrooms. Fidelity was observed in each treatment classroom several times a month and the first author conducted monthly interviews with the teachers to document barriers and successes during the implementation.

Each of the three treatment classrooms was assigned an MTSS coach. The coach for the two half day classes had a bachelor’s degree in psychology and the coach for the full day class was a school psychology doctoral student. The first author collaborated and mentored the coaches throughout the study, and occasionally provided direct support to the teachers and teaching assistants. The informed consent process and pretesting phase occurred during September and October of the school year. Before teachers began delivering Story Champs in their classroom, they attended a two-hour didactic training on Story Champs and watched a coach demonstrate one or two intervention sessions in their classrooms. They also learned to administer and score the NLM-Retell. During the training session, they practiced several times but were not required to reach a criterion. Because one of our research questions was about the fidelity and reliability the teachers could achieve we did not train them to mastery as we did the research assistants (see below). Coaching and feedback were thereafter provided approximately twice a month. All teachers began delivering the large group procedures mid November and continued with the large group procedures for four weeks. The recommended dose of large group Story Champs was two times a week during the first four weeks. After four weeks, a progress monitoring probe was conducted. In collaboration with the researchers, the teacher and teaching assistant team identified children for small group and individual intervention, which began in January. Children who scored between atwo and seven on the progress monitoring probe were assigned to the small group instruction, whereas children who scored between zero and two were assigned to individual instruction.

Once a month from December to April, the researchers asked the treatment teachers and teaching assistants to complete a questionnaire and conducted interviews with the Head Start teams to gather feedback about implementation. The teachers and teaching assistants conducted progress monitoring probes monthly to examine the extent to which the children were making progress and to identify when modifications were needed. The teachers and teaching assistants were free to move children in and out of intervention groups based on the NLM-Retell results and other observations. From January to April, the recommended dose of intervention was one large group lesson per week and two small group or individual lessons per week. The researchers provided the teachers with dose tracking form, which consisted of a simple log for documenting the date the session was conducted and the students who were present. Teachers and teaching assistants did not consistently complete the dose tracking forms, and therefore we are unable to report the exact dose that was achieved. However, through the monthly interviews, we were able to ascertain that the children attending the full day classroom received approximately 90% of the recommended dose, children in classroom B received about 50% of the recommended dose, and children in classroom C received approximately 75% of the recommended dose.

After each lesson, teachers and teaching assistants sent a Take Home Activity home with the children. Take Home Activities were single sheets of paper with the illustrations and the story printed in color. There were simple instructions for the parents to help them engage the children in storytelling activities using a familiar story from the school lessons. This component of the intervention was optional and the use of the Take Home Activities was not monitored.

Intervention

The independent variable consisted of four major components integrated together in a MTSS fashion. The components included: large group narrative instruction, small group narrative intervention, individual narrative intervention, and progress monitoring probes using the NLMRetell task. The teachers and teaching assistants implemented all of the components with support from their MTSS coaches. Story Champs, a multi-tiered narrative intervention curriculum, was the program used to deliver large group, small group, and individual interventions. Specific steps for each type of tiered lesson are briefly described in the introduction section, detailed in the Story Champs manual (Spencer & Petersen, 2012a), and outlined in the master lesson plans (procedural checklists) in the appendix. In addition, videos of the large group (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V4HzbfRiS6A) and small group (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqlUxtBbUrU) procedures can be viewed online.

Measurement

To address the first question of efficacy, the NLM-Retell task was used as a proximal measure because the skills tested are directly related to the skills taught in Story Champs. Nonetheless, the NLM stories were novel to the children at the time of assessment, which provided some evidence that their performance represented improved storytelling and language skills and not just familiarity with the stories. Another measure, the Assessment of Story Comprehension (Spencer, Goldstein, Kelley, Sherman, & McCune, 2017), served as a moderately distal outcome measure because the skills tested are not directly taught in the Story Champs program, but stories are used in both so they are similar. At three time points (fall, winter, and spring), researcher assistants administered these two measures. Teachers and teaching assistants also administered a single NLM-Retell to all of the children in the classroom for progress monitoring purposes once a month during the study. Teachers and teaching assistants (in collaboration with the researchers) used the results of the progress monitoring probes to determine if what they were doing was working and to make intervention modifications if needed. Because the teachers and teaching assistants were considered participants and not researchers, trained to mastery, the results of the progress monitoring probes are not considered outcome data. Rather, they are part of the independent variable of implementing a multi-tiered system of language support.

Narrative Language Measures – Retell. Undergraduate research assistants administered the NLM-Retell measure (see sample in appendix). The first author provided didactic instruction on the administration and scoring procedures. The research assistants were allowed to practice for as long as they needed to master the administration procedures. To be qualified to administer the NLM-Retell, each research assistant was required to administer the measure to one of the MTSS coaches multiple times until it was administered with 100% fidelity. To learn how to score, research assistants read the scoring manual and practiced scoring. To be qualified to score the NLM-Retell, each research assistant had to score 10 retells with at least 90% agreement with the first author. Administration of the NLM-Retell is standardized. Before beginning the administration steps, the examiner placed a booklet with five pictures that corresponded to the NLM story in front of the child. The examiner read the script, “I’m going to tell you a story. Please listen carefully. When I’m done, you are going to tell me the same story.” Then, the examiner read the story with a moderate pace and normal inflection while pointing to the pictures in front of the child. After the examiner read the story, he or she said, “Thanks for listening. Now, you tell me that story.” Only standardized, neutral prompts were allowed; “It’s okay. Just do your best.” And I can’t help you but just tell the parts you remember.” When the child appeared to be done retelling the story, the examiner asked, “Are you finished?” The same administration procedures were taught to the teachers and teaching assistants.

Of the 25 NLM parallel stories, teachers and teaching assistants used the stories allocated for progress monitoring (16) whereas the research assistants used the stories designed for benchmark assessments in the fall, winter, and spring (9). At the three assessment points, each participant was administered three NLM stories in random order at each assessment point. Administration of three NLM stories took about 5-8 minutes. All three child retells were scored and the best score of the set of three was used in the analyses. This procedure reduces confounds such as distraction, motivation, and background information impeding the validity of the results. This is especially important for very young children who are not accustom to taking tests and because the assessments took place in the classrooms surrounded by commotion and noise.

Each assessment session was audio recorded. Research assistants completed the NLMRetell scoring while listening to the audio files so that they could re-listen as needed. Given the noisy conditions of the classroom during assessment, and that young children do not always speak clearly and loudly, it was necessary to listen to the audio files carefully. To score, the research assistants adhered to the guidelines in the NLM manual. Retells were scored for the inclusion, clarity, and completeness of each story grammar element. A score of 2 was awarded for a complete and clear response, 1 was scored for an incomplete or unclear response, and 0 was scored when the child did not include the specific story grammar element. Retells that included a basic complete episode (i.e., problem, attempt, consequence or ending) were given bonus points. In addition to the story grammar elements, children’s retells were scored for the inclusion of language complexity using a frequency count. The words then, because, when, and after earned one point for each use up to three points, except for the word then, for which the maximum points possible was one.

possible was one. The NLM preschool (Spencer & Petersen, 2012b) forms have adequate alternate form reliability (r = .85, p < .0001) and strong evidence of concurrent validity (r = .88-.93). Factor analyses reveal that the retell task loads on two constructs—comprehension and production while the personal generation task loads primarily on production and the answering questions task loads primarily on comprehension. Administration and scoring of all the NLM tasks are standardized, and research has yielded high fidelity of administration (91-98%) and scoring agreement (91-96%; Petersen & Spencer, 2012; Petersen & Spencer, 2016). Within the current study, fidelity with which the research assistants administered the NLM-Retell was calculated for 35% of the total number of retells collected at fall, winter, and spring. The mean fidelity was 98.9% (range = 75%-100%). Independent scorers also examined 35% of the retells collected at fall, winter, and spring. Point-by-point scoring agreement was calculated between the two independent scorers. The mean scoring agreement was 92.7% (range = 72.7%-100%).

Assessment of Story Comprehension. The Assessment of Story Comprehension (ASC; Spencer et al., 2017) was used as a moderately distal outcome measure. The ASC is similar to the NLM in that a short story is read to the child, but it differs in the responses expected of the children. In the NLM, children retell stories and in the ASC, children answer a series of recall and inferential questions. Like the NLM, the ASC stories reflect personally relevant themes such as someone ruining something, wanting to play with someone, and breaking a favorite toy. However, the ASC stories are longer and more complex than the preschool NLM stories so that less common vocabulary words can be supported with story context information. Moreover, the ASC does not have pictures available to use during administration like the preschool NLM. The primary purpose of the ASC is to assess preschoolers’ higher-level comprehension skills such as vocabulary and inferencing and to retain authenticity for young preschool children. The ASC can be used to identify children who need support in language comprehension and to monitor language comprehension growth over time.

There are nine parallel ASC forms to align with seasonal administration (three at a time) in fall, winter, and spring. Each child was administered a unique sequence of ASC forms. The first three ASC forms were administered in the fall, the next three in the winter, and the final three were administered in the spring. At fall, winter, and spring, all three administrations were scored, but only the best score of the set was used in the analysis. This strategy helped reduce potential confounds related to motivation, background knowledge, and distractions during ASC administration.

Research assistants were trained to administer and score the ASC. They attended a onehour training workshop in which they learned about and practiced administering the ASC. To be qualified to administer the ASC, each research assistant had to administer the ASC to one of the MTSS coaches with 100% fidelity. Research assistants read the ASC manual to learn how to score the assessment and practiced using 10 ASCs prepared for training purposes. To be qualified to score the ASC, each research assistant had to score an additional 10 ASCs and achieve 90% agreement with the first author.

Administration of the ASC is standardized and takes approximately 2-3 minutes per story and 8-10 minutes for a set of three. Examiners read the introduction script, “You are going to listen to a story. It is called Danny and the Big Hill. Hmmm. I wonder what will happen in this story. Let’s think about the title, Danny and the Big Hill. What do you think will happen?” The first item involves prediction based on the title. Children’s responses were recorded on the ASC protocol. Then the examiner said, “Now you are going to listen to the story. Listen carefully because I’m going to ask you some questions about the story. Are you ready?” The examiner read the story using normal inflection and at a moderate pace. When he or she was finished, he or she said, “Thanks for listening. Now I’m going to ask you some questions.” Items 2, 4, and 6 of the ASC are recall questions about what the character was doing and what happened in the story. Items 3, 5, and 7 are inferential questions that require children to connect two parts of the story or use background information to answer the question accurately. The final question is a definitional vocabulary item. Each story has one word with contextual support and this item requires the children to define the word. If a child is unable to give a correct definition, the examiner follows up with a choice of two. For example, “Does apologize mean to ask a question or to say sorry?” Children’s responses to the questions were recorded on the ASC protocol and scored later.

ASC administrations were audio recorded, but the recordings were only used for scoring when the examiner was unable to hear or understand responses during the administration. Otherwise, the ASCs were scored within a few days of administration using the written responses recorded on the protocols. ASC scoring guides for each story were developed to promote reliability scoring. The guides include sample answers for items 1-7 that qualify for 2, 1 or 0 points. Generally, however, the scoring guidelines suggest that 2 points are awarded for clear and complete answers, 1 point is scored for incomplete or unclear answers, and 0 points are given for incorrect answers. The definitional vocabulary item is scored on a 0-3 scale where 3 points are given for a complete and accurate definition, 2 points are given for a partially complete definition or an example, 1 point is given if the child answers the choice of two follow up question. A total of 17 points are possible for each of the ASCs.

Fidelity with which the research assistants administered the ASC was calculated for 35% of the total number collected at fall, winter, and spring. The mean fidelity was 99.5% (range = 78.5%-100%). Independent scorers also examined 35% of the ASCs collected at fall, winter, and spring. Point-by-point scoring agreement was calculated between the two independent scorers. Across all time points, the mean scoring agreement was 92% (range = 52%-100%).

Fidelity of Story Champs

To document the extent to which Head Start teachers and teaching assistant could implement the Story Champs interventions with fidelity (question two), MTSS coaches observed each type of intervention in each classroom at least once a month. Because the teachers did not carefully track the dose and the coaches were not present in the classrooms every day, we are unable to determine the portion of the total interventions our fidelity observations represent.

When fidelity observations were conducted, the MTSS coach sat in an area that did not disrupt the lesson but close enough to hear. She used the procedural checklists (see sample in appendix) as a basis for judging adherence to the intervention steps. A checkmark was made for each step that was completed correctly. In addition, the MTSS coaches answered three questions about the quality of prompts, corrections, and differentiation that were observed. Observations indicating that the behavior occurred “always” were given 2 points, behaviors observed “sometimes” were given 1 point, and behaviors observed “never” were given 0 points. These were added to the adherence steps to yield the percent of steps completed accurately and with quality (correct steps plus quality points divided by the total number of steps plus total number of quality points).

Fidelity and Reliability of NLM

Research questions three and four address how well the teachers and teaching assistants were able to administer and score the NLM-Retell task. Because MTSS models require assessment data as the basis for identifying children for the different tiers, and for making ongoing decisions, it is essential that the end users are able to use the assessment tools appropriately. Teachers and teaching assistants administered one retell probe to all of the children in their class once a month.

The Head Start teachers and teaching assistants used audio recorders to record their assessments. The teachers and assistants were given a set of 16 NLM stories/protocols (see sample in appendix) for each child. The teachers and teaching assistants scored directly on these protocols. When the study was complete, the researchers collected the protocols. MTSS coaches listened to 100% of the audio files and used a fidelity checklist to judge the extent to which the teacher and/or teaching assistant administered the NLM correctly. At the same time, the MTSS coach scored the child’s retells without referencing what the teacher or teaching assistant had scored. The NLM-Retell fidelity checklist consisted of eight items that measured how closely the examiner adhered to the script and read the story word for word with normal inflection and at a moderate pace. Point-by-point agreement was used to calculate scoring inter-rater reliability.

Feasibility Questionnaire

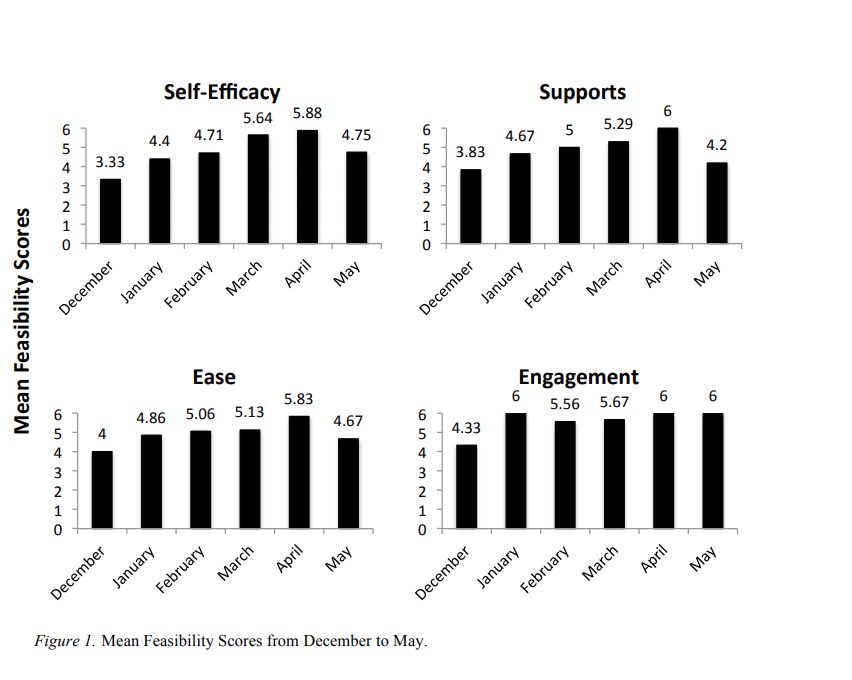

To examine the extent to which Head Start teachers and teaching assistants perceived Story Champs and the NLM to be feasible in their classrooms when implemented in a multi-tiered fashion (question five), we created a 26-item questionnaire. Twenty-two of the items were Likert scale items, where 0 represented Strongly Disagree and 6 represented Strongly Agree. These items were grouped into four categories: self-efficacy, supports, ease of use, and child engagement. Sample items in the self-efficacy category included I am able to use Story Champs effectively and I am comfortable making modifications to fit the needs of my students. For the supports category, sample items included I do not need additional supports to deliver Story Champs and The center director supports the use of Story Champs. Ease of use was intended to determine if the teachers had enough time to plan and implement Story Champs and whether they could fit the NLM and the interventions in among their other tasks. Sample items for child engagement included My students are engaged during Story Champs activities and My students enjoy Story Champs. Fifteen of the items were about Story Champs whereas seven items were about the use of the NLM-Retell measure. The final four questions were open-ended so that teachers and teaching assistants could report their favorite part, their least favorite part, what modifications they made, and suggestions they had to the research team about how to improve the program.

MTSS coaches gave a questionnaire to each teacher once a month about the same time they administered the progress monitoring probes but before the interview with the researcher. The teachers’ and teaching assistants’ answers to the open-ended questions served as a guide for discussions. Interviews lasted approximately one hour. In addition to the content in the feasibility questionnaire, the researcher worked with the teachers and teaching assistants to interpret the results of the NLM-Retell measure and make data-based decisions.

RESULTS

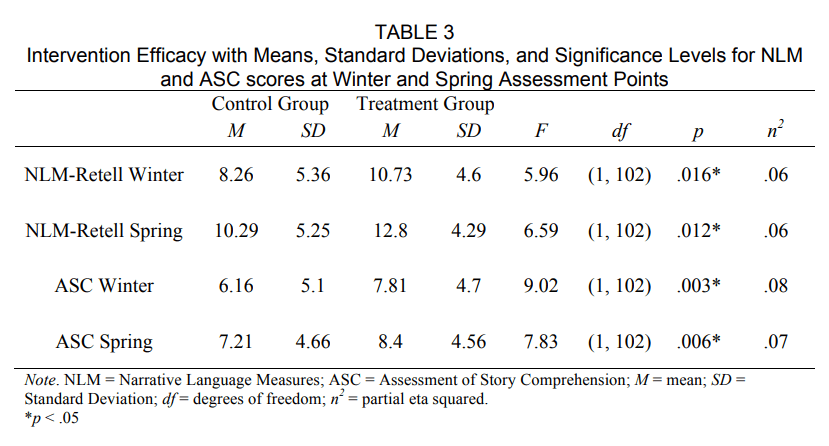

With respect to the first research question, an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used to determine the effects of the Story Champs intervention on NLM-Retells and ASC scores at both winter and spring assessment points after controlling for group differences. Prior to this analysis, data were screened for normalcy using an analysis of variance (ANOVA), homogeneity of regression slopes, and homogeneity of variances. All assumptions were met for the ANCOVA procedure. Using a significance level of .05, results indicated that there were statistically significant group differences for the intervention group on the winter NLM-Retells, F(1, 102) = 5.96, p = .016, partial η 2 = .06 and spring NLM-Retells, F(1, 102) = 6.59, p = .012, partial η 2 = .06, with medium effect sizes. There were also statistically significant differences in ASC scores between groups at the winter, F(1, 102) = 9.02, p = .003, partial η 2 = .08 and spring assessment points, F(1, 102) = 7.83, p = .003, partial η 2 = .07 favoring the intervention group, with medium effect sizes (see Table 3).

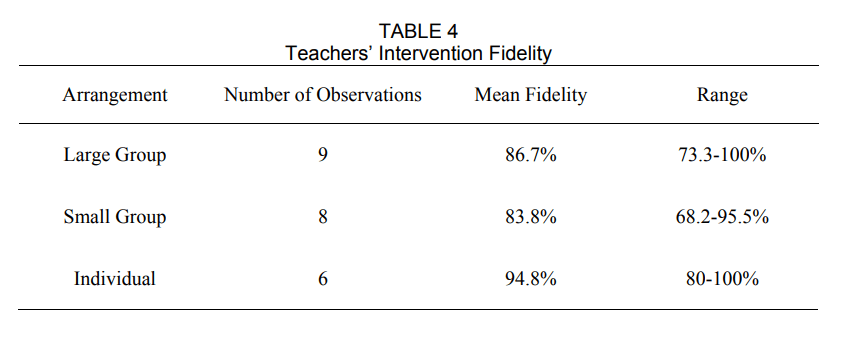

Teachers’ and teaching assistants’ ability to implement the tiered interventions correctly and with quality was monitored to address research question two. Overall procedural fidelity was moderately-strong across all group arrangements implemented by teacher and teacher-assistant teams. For the large group procedures, mean fidelity was 86.7%; for the small group procedures, mean fidelity was 83.8%, and for the individual procedures, mean fidelity was 94.8%. The number of observations for each tier of intervention, the mean fidelity, and ranges are displayed in Table 4. There were more opportunities to observe large group Story Champs and fewer opportunities to observe individual interventions.

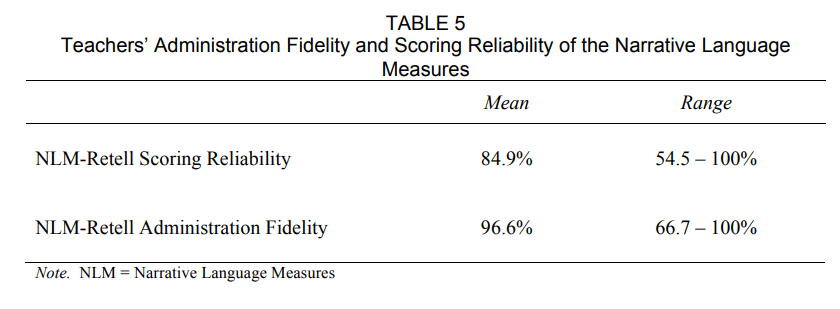

To address research questions three and four, we assessed the extent to which the Head Start teachers and teaching assistants were able to administer and score the NLM-Retell measure. Mean administration fidelity was 96.6%, while point-by-point scoring agreement with the coaches was 84.9%. These data are displayed in Table 5.

Teachers’ perceptions of the feasibility of multi-tiered intervention were averaged across all the teachers and teaching assistants who completed the questionnaire each month. Although there were subtle differences between the reporters, in general, all of the teachers’ reports followed a consistent pattern. Figure 1 shows mean feasibility scores across the months. The first month of implementation was the most difficult for the Head Start teachers and teaching assistants. They reported lower self-efficacy, receiving fewer supports from the other staff and administrator, more difficulty with implementing the procedures, and lower child engagement. Improvements were noted in all areas from January to April, with very high feasibility reported in March and April. In May, however, scores in self-efficacy, supports, and ease of implementation decreased. Child engagement remained high in May.

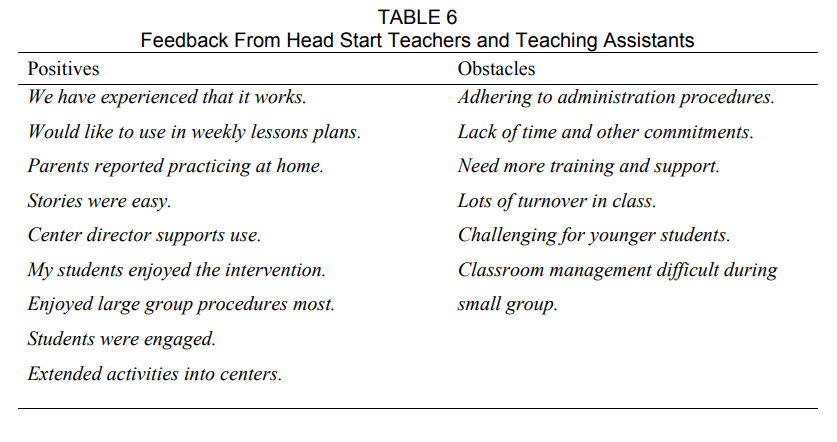

The open-ended items on the feasibility questionnaire allowed us to capture the teachers and teaching assistants’ thoughts about the things they liked and the obstacles they experienced. We examined all of the questionnaires for comments and found that there was a great deal of overlap between comments and themes. In Table 6, we have provided sample statements that reflect the general themes. The positive comment that was made most consistently was how much the children enjoyed the lessons. The obstacle that was repeated more than others was about time and the balance needed to complete all of their other tasks.

DISCUSSION

Efficacy of interventions is of paramount importance. In the evidence-based practice climate, educators must know what works. But, there is also the matter of how well a given intervention integrates or fits into real classroom environments and systems (Albin, Lucyshyn, Horner, & Flannery, 1996; Strain, Barton, & Dunlap, 2012). Real classrooms do not operate in a clean and completely organized manner, as is the case in the laboratory (Evans & Weist, 2004). Schoolbased interventions are ultimately implemented in chaotic, busy environments that, during efficacy trials, are typically moderated by the intensive involvement of researchers. This poses real challenges for educators who attempt to apply an empirically supported intervention in their natural setting (Adelman & Taylor, 2000; Harn, Parisi, & Stoolmiller, 2013). Research that encompasses implementation variables can help transport research into practice (Fixsen et al., 2005).

Although tiered systems of support around behavior have a rich history in early childhood settings (Benedict, Horner, & Squires, 2007; Fox, Dunlap, & Crushing, 2002), multitiered systems of instruction targeting literacy are relatively new in preschool settings (Buysse & Peisner-Feinberg, 2013; Greenwood et al., 2011). In addition, differentiating during small group lessons is common in preschools; however, explicit literacy lessons accompanied by a presentation manual are less common (Bailet, Repper, Murphy, Piasta, & Zettler-Greely, 2013). Despite an abundance of research from K-3 investigations, the findings from MTSS literacy models do not automatically apply in Head Start preschools. Early childhood has a different set of factors relevant to the implementation of MTSS. Therefore, the need to examine variables that promote or impede the implementation and sustainability of interventions is significant. For this implementation study, we merged questions of efficacy and feasibility when a multi-tiered intervention program was delivered by Head Start teachers and teaching assistants in their active and hectic environments. This project was built upon four previous investigations of the Story Champs program, in which researchers and research assistants delivered the lessons and completed all of the assessments. Moreover, this was the first examination of Story Champs when all three tiers of instruction were integrated into classrooms and the NLM guided formative assessment.

Efficacy of Multi-Tiered Narrative Intervention

The efficacy results indicate that the intervention, when delivered by the Head Start teams, was effective at producing statistically significant improvements on story retelling and language comprehension, with medium effect sizes. Both of these outcomes are highly meaningful for young children. Improvements in these skills are likely to impact broader comprehension skills related to storybook read alouds, inferencing skills, and vocabulary development. With respect to language production, the improvements children made in storytelling suggest that, at the end of the year, they produced longer more complete sentences and used more complex sentences to convey past events. Among many anecdotal comments about how well the treatment group was talking, one center director, who did not have a full picture of what the intervention was, reported that of the three classrooms in her center, the treatment classroom was the only class in which the children could carry on an extended conversation with her. The children were friendlier and more confident. She said that the differences between the classes were obvious and exciting.

Children who received the treatment were likely much more prepared for kindergarten as their language comprehension and production skills met multiple early learning objectives (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010; Teaching Strategies, Inc., 2010). It is particularly important to focus on the language of young children who are at risk for future reading comprehension difficulty (McNamara & Kendeou, 2011). Children who attend Head Start preschool programs tend to have highly disproportionate rates of reading difficulty (National Center of Education Statistics, 2015). This high percentage of reading difficulty has not improved in any meaningful way over the past 20 years (National Center of Education Statistics, 2015). It is clear that the almost exclusive focus on decoding in the early years has not made a significant impact on later reading outcomes. Because the primary focus of school-age reading assessments is on reading comprehension, it only makes sense that decoding and comprehension should be of concern.

Children who have stronger language skills do better in school (Mehta, Foorman, Branum-Martin, & Taylor, 2005; Griffin, Hemphill, Camp, & Wolf, 2004; Bishop and Edmondson, 1987; Fazio, Naremore, and Connell, 1996). Instead of waiting until children struggle with reading comprehension, which isn’t validly measured until second or third grade, we can instead intervene early by measuring language comprehension and incorporating MTSS for language at a very young age. The children in this study who participated in MTSS for language made significant improvements in their ability to retell and answer questions about complex, literate narrative language that is reflective of the written language they will need to decode and comprehend in school. The language skills that the children attained lay the foundation for later reading comprehension and academic language (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zhang, 2002; Dickinson, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, 2010; Hirsch, 2003; Storch & Whitehurst, 2002; Tunmer & Chapman, 2012; Walker, Greenwood, Hart, & Carta, 1994). This study offers preliminary evidence that MTSS for language can be implemented at an early age, and that young students can make meaningful, significant gains in their use and comprehension of literate, academic language.

Feasibility of Multi-Tiered Narrative Intervention

Research questions two through four addressed the extent to which the Head Start teachers and teaching assistants were able to implement the Story Champs intervention and administer the NLM-Retell measure with fidelity and score the NLM reliably. A general standard for high fidelity and reliability is 90%, whereas 80% is acceptable. The teachers and teaching assistants were able to meet the acceptable standard. Although the teachers’ and teaching assistants’ fidelity and reliability scores were lower than the research teams’ in the current and previous studies, it was encouraging to see that their fidelity and reliability was within acceptable limits. Small group Story Champs was more challenging for the teachers and teaching assistants because those lessons were conducted during learning centers when the children are engaged in a variety of activities around the classroom. The children who were not participating in the small group intervention were noisily playing. In contrast though, large group Story Champs involved the entire class so there were not added distractions for the children and the teacher. All of the teachers and teaching assistants reported that the small group lessons were most challenging because they had never taught small group explicit lessons, and managing the behavior of three to four children at a time was difficult.

Based on the mean fidelity scores, it appears that the individual lessons (94.8%) and the NLM-Retell administration (96.6%) were easiest for the teachers to do. This is likely because during these activities the teacher or teaching assistant was working with only one child at a time. It was encouraging to find that the NLM-Retell scoring agreement was within an acceptable range (84.9%). We expected this to be the most challenging aspect of the MTSS because the teachers reported that this type of assessment was unfamiliar to them. The inter-rater reliability for the NLM-Retell indicates that with some training and practice, children’s retells can be scored by Head Start teachers and teaching assistants. If a valid assessment can be scored reliably, then it can be used for making decisions in a formative manner.

Results of the feasibility questionnaire produced a number of interesting findings. The consistent pattern across all the teachers and teaching assistants was that the feasibility was lowest during the first month they implemented the program, but steadily improved over the next four months. It is likely that as the teachers and teaching assistants became more comfortable delivering the interventions and administering the assessment, they perceived the activities as easier, the children were more engaged, and others were more supportive of the implementation as a whole. Feasibility scores for the Story Champs interventions were overall higher than the feasibility scores for the NLM. This was not surprising since this type of progress monitoring was unusual to the Head Start teachers and teaching assistants. One area that did not show incremental increases was child engagement. The increase in engagement to the maximum score came in the second month of implementation and remained high until the end of the year. The most unusual finding, however, was that teachers reported a decrease for self-efficacy, supports, and ease of implementation in the last month of school. There was a significant drop in scores in May in all feasibility categories except engagement. This was puzzling. The only anecdotal evidence that supports this type of drop was that teachers reported that, in the late spring, the students’ behavior became more difficult to manage. There were more field trips and visitors during the last month, which meant there were more activities competing for the time that was typically used for Story Champs.

Based on the teachers’ and teaching assistants’ open ended remarks about the things they liked and the obstacles they encountered, a number of discoveries were made. Overall, the teachers and teaching assistants appeared to enjoy the program and reported that the children made meaningful language gains. They thought the lessons were fun and engaging, and that parents, center directors, and other staff members in the classroom supported the implementation of multi-tiered narrative intervention. Some of the teachers took it upon themselves to extend the concepts into other parts of their day and used the story grammar icons to help children understand books read aloud in the classroom. The obstacles appeared to be the same for all of the teachers at one time or another. For example, initially the teachers reported that it was difficult to adhere to the procedures in the master lesson plans and follow the scripts for the NLM-Retell administration. Teachers reported that classroom management was challenging because the children who were not receiving small group intervention were playing freely. There are other potential options for scheduling that could reduce this obstacle, but since small group instruction was not commonplace in these classrooms, the best time for intervention was during center time. The most significant obstacle was time. Teachers and teaching assistants appeared frustrated with the number of tasks they had to complete every day and that they were not always able to fit everything in. Although they enjoyed the multi-tiered lessons, there was no requirement for them, which meant that Story Champs would be the first thing to slip off the schedule. There was a significant amount of turnover of the staff members in classroom B that was likely responsible for the lower dose of intervention achieved (e.g., 50% of recommended dose).

A number of revisions and additions have been made to the Story Champs program as a result of direct feedback from the Head Start teachers and teaching assistants. One of the new components of Story Champs is the inclusion of center activities. Teachers requested materials to help reinforce the concepts during child-directed activities. We created three specific sets of materials and activities, including sequencing pictures, story strips (for drawing stories), and storybooks. To use the storybooks, a set of blank books goes in a literacy center. Each page of the book has a story grammar icon on it (i.e., character, problem feeling, action, ending) and four lines with plenty of space for drawing. Children draw their pictures that correspond to the icons and then dictate each part of the story for the teacher to write. Another revision involved more information in the master lesson plans and the development of a sample script. Because explicit instruction was less familiar to the teachers, one requested more help with what to say while she learned how to deliver the lessons. We created scripts for one teacher to use, but as soon as she was comfortable with the lessons, she did not need to refer to it anymore. This script has since been added to the Story Champs manual. Finally, teachers suggested that videos would help them learn the program. None of the teachers read the manual even though the researchers gave them one and asked them to read it. A video manual instead of a paper version may be a more accessible way to provide training to busy teachers.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study makes an important contribution to the current knowledge on MTSS models in early childhood education, there are a number of weaknesses and areas for future study that should be noted. For instance, due to limited resources, we were unable to document the type and quality of instruction in the control classrooms. We would have also liked to conduct more thorough and more frequent observations in the treatment classrooms to document any carryover effects. One teacher commented that because of Story Champs and the NLM, she knew what to expect from her students in terms of language. Others have reported that teachers learn to recast and expand children’s language through the use of Story Champs, but we were unable to document whether this occurred outside of Story Champs lessons. Future research should examine the extent to which teachers’ general language facilitation improves as a result of using Story Champs. Another weakness of this study was that we were unable to conduct a follow up probe to examine the extent to which the language advantage sustained because post-testing was completed just before the school year ended. It is unknown whether the oral language production and language comprehension improvements we observed would be robust enough to have a durable impact. Given the significant disadvantage the child participants had in language (e.g., mean CELF-P of 79), it may take multiple years of intensive language promotion to significantly improve their academic achievement (Dickinson et al., 2010; Paris, 2005). Nonetheless, this is a worthy area of study for the future. Few studies have followed children long enough to examine a causal link from early oral language intervention to later reading comprehension (Fricke, Bowyer-Crane, Haley, Hulme, & Snowling, 2013). It is possible that limited general classroom organization seen in the comparison to Classroom C could have reduced the language growth the children in that classroom experienced. Preschool classroom quality predicts literacy outcomes in that the higher the classroom quality the more the students learn (Cunningham, 2010). In this study, the differences in general classroom organization favored the treatment group. Unfortunately, with such small samples further analysis of ELLCO differences and their impact on the outcomes was not possible. Future research with larger samples should examine the extent to which classroom organization and quality influence the extent to which children respond positively to Story Champs. Finally, there are several other aspects of implementation that still need to be resolved. A stronger training regimen is needed, and the format for how that occurs needs to be examined through an implementation science lens. The issues of mandated requirements and the absence of small group explicit instruction in the participant classrooms need further exploration. Without accountability and systemic requirements, a program like Story Champs has a small chance of surviving, even if it benefits children.