Abstract

Standards of academic performance place a high demand on students’ English language. To help Spanish-speaking preschoolers who are developing English as a second language meet these demands, researchers recommend strengthening their first language to facilitate the development of their second language. Head Start teachers and research assistants delivered 12 Spanish and 12 English language lessons to eight preschoolers in small groups. The lessons targeted storytelling and vocabulary and occurred 4 days a week for 20 minutes. A multiple-baseline experimental design across groups was used to examine the effect of the Spanish–English narrative intervention on children’s retelling skills and a pretest-posttest design without a control group documented children’s acquisition of the target words. Results indicated that children made gains in English retelling while maintaining their already high Spanish retelling skills. Improvements in vocabulary were observed in English but not in Spanish.

Keywords

narratives, vocabulary, dual language, storytelling, bilingual development, language intervention

Hispanic/Latino children represent 38% of the enrollment in Head Start preschool programs across the United States, and about 85% of those children are from Spanish-speaking families (Office of Head Start, 2016). Dual language learners (DLLs), in this case, Spanish-speaking preschoolers learning English as a second language, are at high risk of later academic and reading difficulties in English (National Center for Education Statistics, 2015). Over 80% of fourth-grade Hispanic children and 92% of fourth-grade English language learners read below a proficient level (National Center for Education Statistics, 2015). This group of students is disproportionately placed into special education in the United States (Denton, West, & Walston, 2003). Although the majority of them do not have language-related disorders, their reading performance in English is not meeting expectations.

For children whose first language is Spanish, there is growing evidence to suggest dual language instructional approaches can lead to greater academic achievement and proficiency in their second language (August & Shanahan, 2006; Rolstad, Mahoney, & Glass, 2005; Slavin & Cheung, 2005). Positive outcomes result from comprehensive early childhood bilingual education programs (Barnett, Yarosz, Thomas, Jung, & Blanco, 2007; Durán, Roseth, Hoffman, & Robertshaw, 2013) and dual-language supplemental interventions for children with disabilities (Restrepo, Morgan, & Thompson, 2013) and children with risk factors (Lugo-Neris, Jackson, & Goldstein, 2010; Méndez, Crais, Castro, & Kainz, 2015). A number of researchers suggest that high-quality early childhood practices for DLLs, whether comprehensive or supplemental, should incorporate the children’s home language, explicitly teach meaningful vocabulary words, and foster formal or academic language necessary to succeed in school (Castro, Espinosa, & Paez, 2011; García & Miller, 2008).

Research has clearly indicated that oral language in early childhood is significantly related to later reading and academic success (National Early Literacy Panel, 2008; National Reading Panel, 2000). In particular, reading comprehension relies heavily on oral vocabulary (Cain & Oakhill, 2011; National Reading Panel, 2000; Perfetti & Hart, 2001; Verhoeven & Van Leeuwe, 2008) and narrative ability (e.g., Griffin, Hemphill, Camp, & Wolf, 2004; Mehta, Foorman, Branum-Martin, & Taylor, 2005), which are suggested targets for DLLs (Castro et al., 2011). Although the majority of research linking vocabulary and narrative language to reading comprehension is correlational, Clark, Snowling, Truelove, and Hulme (2010) found a causal relationship between their vocabulary and narrative oral language intervention and reading comprehension of third graders. Earlier interventions could prevent reading comprehension problems, and language interventions that incorporate preschoolers’ home language could have a powerful effect on later reading achievement of DLLs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of a Spanish–English narrative intervention with embedded vocabulary instruction on the vocabulary and narrative skills of DLLs.

Evidence suggests that storybook-based vocabulary instruction in both English and Spanish yields vocabulary growth in both languages, or at the very least helps maintain the vocabulary already acquired. Restrepo et al. (2013) found that a dual-language vocabulary intervention facilitated English receptive and expressive vocabulary acquisition to the same extent as the English-only intervention and that Spanish vocabulary was also supported. Similarly, Méndez et al. (2015) found superior effects for the use of preschoolers’ home language (Spanish) and English over the use of the participants’ second language (English) only.

Oral, narrative-based language interventions have recently emerged in the research literature as an effective means of addressing the academic language skills of diverse learners (Brown, Garzarek, & Donegan, 2014; Gillam & Gillam, 2016; Spencer, Petersen, Slocum, & Allen, 2015; Weddle, Spencer, Kajian, & Petersen, 2016), but no studies are investigating the effects of a dual language narrative intervention. Likewise, there are no narrative intervention studies that targeted the acquisition of specific vocabulary words. Most early educators are familiar with storybook interventions which are a commonly used method of promoting vocabulary and comprehension (Roberts, 2008; Van Kleeck, 2008). However, narrative interventions may have some powerful advantages over storybook reading. First, in narrative interventions, the stories can be engineered to be the exact structure, length, and complexity needed to foster the academic language of children, regardless of their age and language development. Target vocabulary words and contextual support can be intentionally embedded in the narratives used during the intervention (Lee, Roberts, & Coffey, 2017). Second, some storybook reading interventions encourage children to retell parts or entire stories, but it typically requires several repeated readings before young children can expressively retell the story. In narrative interventions, children have several opportunities to retell or tell stories and thereby receive many opportunities to practice using complex academic language related to the stories (Petersen, 2011).

There is good reason to believe that narrative intervention could be a viable dual-language approach for promoting kindergarten readiness of young DLLs. Narratives are replete with complex academic language such as adverbs, adjectives, conjunctions, causal and temporal ties, and subordinate and relative clauses. Most narratives have a basic underlying structure referred to as a cognitive schema which is observed in the quality and number of story grammar elements (e.g., setting, initiating event, attempt, consequence) included in a narrative (Stein & Glenn, 1979). There are many similarities among story grammar elements across languages, and there is evidence suggesting children can transfer story elements and complex syntax across languages (Pearson, 2002). A dual-language intervention can take advantage of the interrelatedness of narrative structure (or schema) and other shared features of Spanish and English (Fiestas & Peña, 2004) languages to hasten the acquisition of academically related oral language (Cummins, 1984; MacSwan & Rolstad, 2005; Petersen, Thompsen, Guiberson, & Spencer, 2015). If stories used in narrative intervention are carefully constructed, they may be able to facilitate the acquisition of vocabulary in addition to promoting narrative structure and complex syntax (Lee et al., 2017).

Current Study

The findings from several research studies examining the efficacy and feasibility of an English-only narrative intervention program (Story Champs; Spencer & Petersen, 2012b) informed the design of a dual-language version of the narrative intervention. In several groups and single-case experimental design studies, Story Champs has improved preschool children’s narrative retell skills, as well as their ability to generate personal stories and answer questions about stories (Spencer, Kajian, et al., 2013; Spencer, Petersen, & Adams, 2015; Spencer, Petersen, Slocum, Allen, 2015; Spencer & Slocum, 2010; Weddle et al., 2016). Many of the preschool participants were Spanish-speaking English learners attending Head Start preschools. While Story Champs has a positive track record with Spanish-speaking English learners, Spanish has not been deployed during Story Champs intervention, and vocabulary instruction has not been systematically embedded in the narratives used for intervention. Based on the evidence that strengthening children’s first language can facilitate the development of their second language (Baker, 2000; Coltrane, 2003; Cummins, 2000; Gibbons, 2002) and the early childhood practices for DLLs should include explicit vocabulary instruction, we developed a dual language (Spanish/English) narrative intervention with embedded vocabulary instruction. In the current study, we investigated the extent to which the dual-language intervention improved preschool DLLs’ narrative retell skills and vocabulary acquisition. The main objective of the dual language intervention was to improve the children’s English language skills (i.e., narrative retells and vocabulary) while maintaining or improving their Spanish language skills. The following research questions were addressed:

Research Question 1: To what extent does a dual-language narrative intervention improve preschoolers’ English narrative retell skills?

Research Question 2: To what extent does a dual language narrative intervention with embedded vocabulary instruction improve preschoolers’ knowledge of targeted Spanish and English words?

Method

Participants

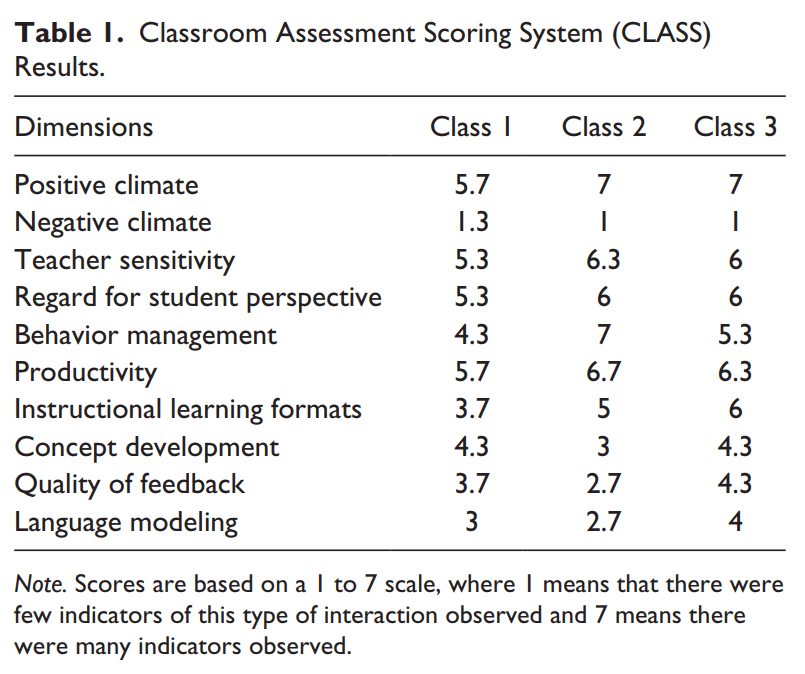

Teacher participants. The director of a Head Start program in the southwestern United States recommended three Head Start teachers serving primarily Spanish-speaking children to participate in this study. The three teachers accepted the researchers’ invitation to participate. According to a demographic survey completed by the teachers, all teachers taught in half-day classes, four days a week. In Class 1, the lead teacher had taught preschool for 26 years, had an associate’s degree, and spoke fluent conversational Spanish, but could not read Spanish well. In Class 2, the lead teacher had taught preschool for 17 years and spoke fluent conversational Spanish, but could not read Spanish well. At the time of this study, she was working on her bachelor’s degree. In Class 3, the lead teacher was a native Spanish speaker from Mexico, was bi-literate in English and Spanish, had been teaching 4 years, and had completed a few college courses. All three teachers were observed using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2008) in the same time frame as this study. Their scores are displayed in Table 1.

Child participants. At the time that parental permission was obtained, parents completed a short demographic survey in their preferred language. Sixteen children from the three classes whose parents identified Spanish as one of the primary languages spoken at home were screened for inclusion in the study. Brief language samples were collected in English and Spanish using the retell section of the preschool Narrative Language Measures: Listening (NLM: Listening) subtest of the CUBED assessment (Spencer & Petersen, 2012a). A score of eight on the English NLM: Listening retell was used as a cut score for the inclusion of research participants because previous research indicated it was a developmental standard for English-speaking preschoolers (Spencer, Kajian, et al., 2013; Spencer, Petersen, & Adams, 2015). Only children who scored 8 or below on the English NLM: Listening retell section were selected for the study. Ten children met the inclusion criteria. One child was eliminated from the study because of frequent absences, and one was removed because he was too reticent to speak and we could not confirm that Spanish was his dominant language.

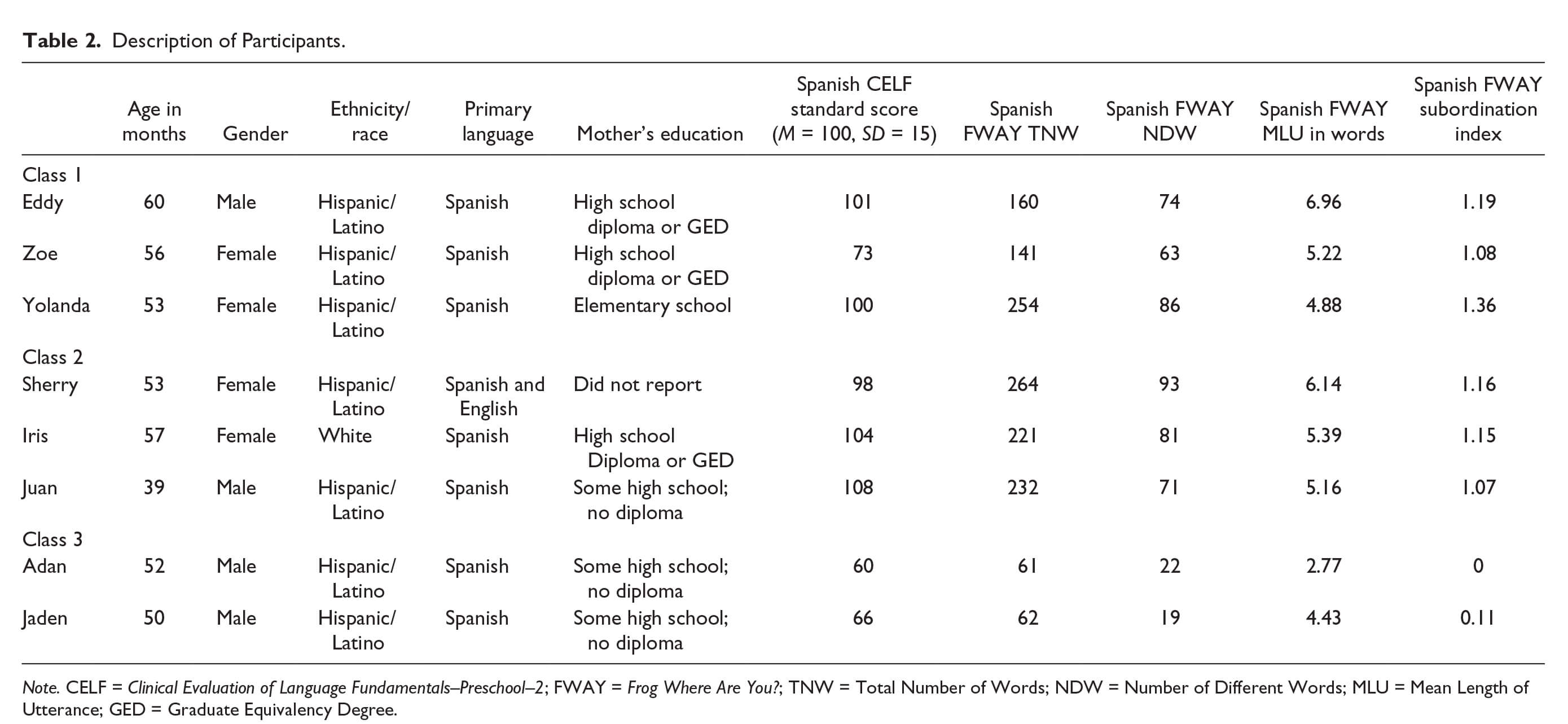

Of the eight research participants, all except one were identified as Hispanic/Latino; one child was identified as White. Spanish was the primary language in seven of the children’s homes, and Spanish and English were the primary languages in the other child’s home. All children came from low-income households. None of the children qualified for or received special education services. The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Preschool–2 Spanish (CELF-P-2; Wiig, Secord, & Semel, 2009) was used to further describe participants’ Spanish language abilities prior to the study. In addition, Spanish language samples were gathered using the wordless picture book Frog Where Are You? by Mercer Mayer (1969). To collect the language samples, an examiner read a short story that went with the illustrations about a boy who loses his pet frog, and children retell the story. Children’s stories were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) software (Miller & Iglesias, 2008). Total Number of Words (TNW) is a measure of language productivity, Mean Length of Utterance (MLU), and the subordination index are estimates of complex language, and Number of Different Words (NDW) is an estimate of a child’s breadth of vocabulary. More information about the CELF-P-2 and the language samples is available by emailing the first author. See Table 2 for additional information; children’s names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

The NLM: Listening (Spencer & Petersen, 2012a; see supplemental appendix for sample record form) was used to elicit narrative retell language samples in English and Spanish. The NLM: Listening is a curriculum-based measurement tool (Deno, 2003) designed to assist educators and clinicians in gathering repeated language samples using standardized administration and scoring procedures. The NLM: Listening preschool version has 25 forms in English and an additional 25 forms in Spanish. Each form features a brief story that highlights a common childhood experience such as getting hurt, forgetting something, or wanting a toy someone else has. The Spanish and English stories are not translations but are designed to be parallel assessments to monitor language progress in both languages over time. Stories were crafted to include consistent and specific linguistic features (e.g., causal and temporal subordination, adjectives, etc.) and story grammar elements (i.e., character, setting, problem, feeling, attempt, ending), which make up the plot and key elements of the story.

To administer the NLM: Listening retell section, an examiner reads the script, “I’m going to tell you a story. When I’m done, you are going to tell me the same story. Are you ready?” He or she then reads the story at a moderate pace with normal inflection and says, “Thanks for listening. Now you tell me that story.” Only neutral prompts are allowed such as “I can’t help you. Just do the best you can.” or “Just tell me all the parts you remember.” Although there are optional story questions and vocabulary questions that could have been used, only the retell portion of the NLM: Listening was used for this study. To score children’s retells, an examiner listens for keywords and phrases that constitute story grammar elements. A score of 2 is given if the child tells the part of the story and it was clear and complete, but only 1 point is awarded if it is unclear or incomplete. If the child does not include the story grammar element in his or her retell, 0 is marked on the record form. When a child tells the main parts of the story that make up an episode (i.e., problem, attempt, consequence, and/or ending), additional episode points are awarded (see supplemental appendix for sample record form). In addition to listening for story grammar elements, an examiner also scores the child’s retell for language complexity features such as the use of subordinating and coordinating causal and temporal conjunctions (e.g., because, then, when, and after). Although the conjunction then is a temporal marker, it does not indicate the use of complex language, and a maximum of 1 point is awarded for its use. However, every time a child uses the subordinating conjunctions because, when, or after, he or she receives a point, up to a maximum of 3 points per word. The story grammar score (with additional episode points) and language complexity score are summed to form a total retell score.

Spanish and English retells collected using the NLM: Listening preschool forms have been examined for their technical adequacy. The NLM: Listening forms have strong evidence of construct validity and strong evidence of concurrent validity (r = .88–.93; Petersen & Spencer, 2012, 2016) when compared with the Renfrew Bus Story (Cowley & Glasgow, 1997) and the Index of Narrative Complexity (Petersen, Gillam, & Gillam, 2008). Inter-rater reliability of the preschool NLM was calculated across 65 independent examiners scoring over 1,500 stories from 163 children. Forty-four percent of the children narrating the stories were bilingual. Mean point-to-point inter-rater reliability while scoring from a transcription is 97%, with a range of 88% to 100% (Pettipiece & Petersen, 2013). Inter-rater reliability from scoring in real-time is 95%, with a range of 64% to 100% (Petersen & Spencer, 2016; Pettipiece & Petersen, 2013). Alternate/parallel forms reliability was calculated in two separate studies with 212 preschool children who were administered all 25 parallel forms. The correlation coefficient across all forms was strong (r = .85). The standard error of measure (SEM) derived from real-time inter-rater reliability is .95, and a standard deviation of 5.23 is 0.26. With confidence set at 90%, the range of scores is ±0.43. When the parallel forms reliability coefficient (r = .85) is used in the SEM calculation, the SEM is 0.78. Thus, with confidence set at 90%, the range of scores is ±1.28.

A researcher-made receptive picture vocabulary task was used to measure growth on the 12 vocabulary words targeted in intervention. For each target, four pictures were arranged on a page and the placement of the target was counterbalanced across words. The same illustrations were used for Spanish and English assessment, but the placement of the target and foils was not the same for both languages. To administer the receptive vocabulary task, an examiner showed the four pictures to a child, and said, “Point to __________.” Correct selections were awarded 1 point for a total of 12 possible points per language. Although reliability estimates were not obtained for this experimental measure, similar receptive picture vocabulary tests have yielded high-reliability results. Cronbach’s alpha, test-retest, and internal consistency results have ranged from .81 to .96 (Brownell, 2000; Dunn & Dunn, 2007).

Materials

Within the dual-language intervention, a variety of materials were used, including carefully constructed stories with illustrations, semi-manualized lessons combined with the stories into a presentation book, pictures to provide multiple exemplars of target vocabulary words, common classroom objects to represent words that are not easily depicted in a photograph (e.g., rough), icons representing story grammar elements, take-home activities for children to tell the stories to a family member, and active responding game pieces to enhance engagement. The assessment materials consisted of paper record forms, pencils, digital voice recorders, and test stimuli.

There were 12 Spanish lessons with 12 comparable English lessons. Each lesson centered on a brief, personally themed story, in which the targeted vocabulary words were embedded. English stories were 75 to 80 words long, whereas Spanish stories were 80 to 85 words long. The Spanish stories were not translations of the English stories, but also included equivalent linguistic features and vocabulary targets (e.g., brincar-leap) to maximize cross-linguistic transfer (Cummins, 2000). In each lesson, one adjective and one verb were explicitly targeted in the context of the story and other contexts using photos or objects (e.g., áspero-rough). We used Beck, McKeown, and Kucan’s (2002) tiered framework to choose words to teach. We aimed to select words that could be functional but less frequently used by preschoolers in English and Spanish. Selected words had to have a child-friendly definition in both languages. Each of the 12 words was embedded in four lessons—two Spanish and two English (e.g., brincar-leap count as one vocabulary target). The distribution of words allowed for repeated exposure of the words across multiple contexts throughout the 24 lessons.

A set of illustrations (five panels for each story) was used to support children as they retold the story featured in each lesson. Colorful yet simple illustrations were individually printed on white cardstock (4″ × 6″). Colorful icons representing the main parts of stories or story grammar elements that are developmentally appropriate for preschoolers (i.e., character, problem, feeling, attempt, ending) were printed on white cardstock (1.5″ square). For each target vocabulary word, photographs were organized into a picture book. Objects from the classroom were required for some lessons. For example, heavy and light objects from the classroom were used to demonstrate the target word heavy.

Three games that were part of the lessons required the use of prepared materials. Story Bingo cards were printed in color on cardstock and were approximately 4″ × 6″ in size. Each bingo card had each of the five main story grammar icons on it in various locations. Story Cubes were small white blocks that had the five icons printed on the sides. Story Sticks consisted of five small colored wooden sticks, each with one of the five icons depicted on the end of the stick.

Take-home activities were single sheets of paper with the featured story in English or Spanish with its accompanying illustrations. Suggestions for how parents can engage their children in storytelling activities were displayed on the top of the page.

Research Design

To answer the first research question, we used a single-case multiple-baseline design (Gast, Lloyd, & Ledford, 2014) with three groups of children, each group with staggered baseline lengths. Multiple-baseline designs are experimental designs because they can control for most threats to internal validity and demonstrate causal relations between the independent and dependent variables. Rather than using a control group to establish the counterfactual condition, single-case research designs benefit from within the child or group experimental control via baseline conditions (Horner et al., 2005). The key indicator of experimental control is that there are at least three demonstrations of causal effect at three points in time, and for the What Works Clearinghouse to consider a study as evidence without reservations at least five data points are needed per condition (Kratochwill et al., 2013). We conducted a pretest, posttest without a control group design to address our vocabulary acquisition research question.

Procedures

Research participants experienced baseline and intervention conditions. During the baseline condition, only the data collection procedures were conducted. No vocabulary or storytelling instruction occurred during baseline except what the Head Start teachers typically provided, which was minimal. During the intervention condition, research participants received daily small group instruction and continued to participate in the data collection procedures. The eight research participants attended school in three different Head Start classrooms, naturally forming three intervention groups for the multiple-baseline research design. In two classes, all three children who participated in the small group intervention were research participants. In the third class, one of the children who originally qualified for the study was absent frequently. Therefore, data are reported for only two of the children. When children were absent, interventionists included a third child from the classroom to maintain the group size of three and to balance the number of opportunities to respond across the sessions and groups. Interventionists chose any child from the classroom who wanted to participate in the lesson but tended to include other children who the teacher indicated might benefit from the lessons. According to single-case experimental design conventions, each group entered the intervention phase when baseline stability had been established (Gast et al., 2014).

Interventionists. Three Head Start teachers implemented half of the dual-language narrative lessons. Two of the teachers completed the small group lessons in English (Classes 1 and 2) and one administered the lessons in Spanish (Class 3). The teachers were allowed to choose which language they were most comfortable using for instruction. Each teacher was paired with one or two researchers who provided intervention in the opposite language. Two native Spanish-speaking undergraduate students provided interventions, opposite teachers, in Classes 1 and 2 and two graduate students taught the English lessons in Class 3. Before delivering interventions, the first author gave the teachers and research team a 1-hour training, which consisted of describing the lesson activities for storytelling and vocabulary and explaining the specific procedures for prompting. Although this served as an introduction, the bulk of the training occurred in the classroom via demonstration and coaching. The first author and graduate students with experience delivering narrative intervention in previous studies shared the responsibilities of coaching the interventionists. Coaching occurred for the first three lessons the Head Start teachers delivered, but the research team needed fewer coaching sessions.

Intervention procedures. Spanish lessons were delivered before the corresponding English lessons so the language of intervention alternated every day (total number of lessons = 24). When possible, lessons were completed every day, Monday through Thursday, lasting 20 to 25 min. Although they were intended to be shorter, as Head Start teachers became more comfortable with the teaching procedures, they were able to deliver the lessons quicker. The research team was able to deliver the lessons in about 15 to 20 minutes.

Each lesson conformed to the same instructional format of seven activities. Only the stories and target vocabulary words changed and lessons were never repeated. In Activity 1, with the illustrations displayed on a table in front of the children, interventionists read the featured story and laid the colored icons on the corresponding illustrations. In Activities 2 and 3, the target vocabulary words were introduced while referencing their use and context in the story. In Activity 4, children named the parts of the story (character, problem, feeling, action, and ending) and listened to the story again while playing a game called Story Gestures. In this game, as the interventionist read each part of the story, children made a gesture that corresponds to each story’s grammar element. For example, when the character was mentioned children put their hands on their heads, and when the problem was mentioned they gave the thumbs down sign.

In Activity 5, children took turns retelling the story individually. The first child used the illustrations and icons to help retell the story. After the first child retold the story, the interventionist removed the illustrations and the second child retold the story with just the icons displayed. Then the interventionist removed the icons and the third child retold the story without visual supports. During each individual retell, the children who were listening played one of the story games. To play Story Bingo, children pointed to the icon that represented the part of the story being retold by their peers. As the child retold each part of the story, the listeners pointed to each of the icons, in turn demonstrating that they were listening and comprehended the story. Story Cubes and Story Sticks were played the same way except the cubes were turned to the proper side displaying the correct icon and the sticks were held up to show that children understood what part of the story their friend retold.

In Activities 6 and 7, the target vocabulary words were reviewed using the photographs and/or common classroom objects to provide additional context for the use of the target vocabulary words. For storytelling activities, children heard the story read by the interventionist twice and retold by peers twice. Each child retold the entire story once as a group and once individually per intervention session. For vocabulary activities, children said each word and definition as a group at least 4 times and individually at least once. With corrections and during storytelling, children had an additional four to six opportunities to say the words and define them.

Interventionists followed the scripts in the presentation book for each lesson, ensuring lessons were standardized; however, it was not essential that the exact words were used. Rather, interventionists were taught to complete the primary objective of each activity and to differentiate based on the children’s language and engagement. For example, for the vocabulary activities (Activities 2, 3, 6, and 7), the required procedures included modeling the new word, referencing the story illustrations or showing a photo or object, having the children repeat the word, defining the word, and having the children define the word. Interventionists used child-friendly signals to cue the children to respond together. For the storytelling activities, interventionists used a two-step prompting procedure to support children’s story retelling. This involved first asking a question when a child was unable to retell a part of the story (e.g., “What was Sam’s problem?”) and then following it with a model (e.g., “Sam felt sick.”) if the child continued to struggle. Children were also encouraged to use the target vocabulary words while retelling the story. Prompts for storytelling (and using the vocabulary words) were individualized because children participated in retells one at a time.

At the end of each intervention session, interventionists gave the children take-home activities that corresponded to the lesson of the day and in the corresponding language. We did not train parents to complete the activities, and their engagement with the take-home activities was not tracked. However, at the end of the study, parents completed a short questionnaire to help us estimate how often they used the storytelling activities with their children. This questionnaire used a scale from 0 to 5, 5 being often and 0 being never. Parents were also asked which language they used most often and how they liked the activities.

Data collectors. Six graduate and undergraduate research assistants served as data collectors for the study. They received training from the first author to administer and score the NLM: Listening retell section and the researcher made receptive picture vocabulary assessment. After a 1-hour didactic training, the research assistants practiced administering the assessments and scoring retells from previously scored samples. Two doctoral graduate students conducted “checkouts” to ensure that the examiners could score the assessments in real-time with at least 90% accuracy and administer the assessments adhering to the standardized procedures with at least 90% fidelity. The six examiners conducted initial scoring and served as fidelity and reliability scorers on assessments that they did not administer and score initially.

Data collection procedures. During the baseline and intervention phases, children’s retell skills were collected 4 days a week (Monday through Thursday), twice in English and twice in Spanish. Students did not attend school on Fridays. Daily collection of retell skills using the NLM: Listening has been conducted in previous narrative intervention research (e.g., Spencer & Slocum, 2010) and is possible because of the large number of parallel forms/stories (Petersen & Spencer, 2012). The same story was never used twice to collect retell samples from the children. When children were absent, it was not always possible to make up their assessment probes. Once the intervention phase began with each group, assessments were conducted before the intervention session on the same day. At the beginning of the baseline condition, children were administered the researcher-made receptive picture vocabulary assessment in both languages. Once all 24 lessons were completed, the picture vocabulary assessments were administered again.

Assessments took place in the classrooms during center times when children were allowed to play freely. One at a time, children were invited to come with an examiner to a small table within the classroom to tell stories. One administration of an NLM: Listening retell took 1 to 2 minutes. Following the child’s retell, the child returned to the classroom activities and the examiner repeated the procedure with another participant. Administration of the receptive picture vocabulary assessments was completed in the exact same manner and also took 1 to 2 minutes each. Examiners scored all of the assessments in real-time on record forms, but children’s retells were recorded using digital audio recorders to allow for an examination of administration fidelity and scoring reliability. Therefore, if examiners were not confident in their real-time scoring, they were allowed to replay the story later and edit their scores.

Procedural fidelity and scoring reliability. One-third (33.33%) of the audio recorded retells produced by each participant in baseline and intervention conditions were randomly selected to be examined for administration fidelity. A second examiner listened to the audio files while using a six-item fidelity checklist to determine the extent to which the examiners adhered to the standardized data collection procedures. The number of items completed correctly out of the total number of items yielded a percent fidelity of administration. The mean baseline fidelity of administration of the NLM: Listening retell procedures was 95% (range = 85%–100%; SD = 6.3) and the mean intervention phase fidelity was 97% (range = 85%–100%; SD = 5.4).

From both baseline and intervention conditions, a randomly selected set of audio recorded retells (approximately 33%) were scored by an independent examiner. Agreements were determined for each of the 10 story grammar and language complexity items (not including the episode because it is based on the scoring of story grammar elements). To agree, both scorers had to give the element the same point assignment (i.e., 0, 1, or 2 points). Inter-rater reliability was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. The mean scoring agreement for baseline retells was 85% (range = 70%–100%; SD = 15.0) and for intervention retells, the mean scoring agreement was 83% (range = 70%–100%; SD = 10.4).

During the intervention condition, all interventionists were observed at 3 times to document the fidelity with which they completed the interventions. Fidelity of intervention observations was not completed during baseline because teachers reported that they did not routinely teach vocabulary via storytelling. In addition, the teachers did not have access to dual-language narrative lessons. To record fidelity, the first author or a trained research team member observed the intervention session live. Observers used a detailed checklist to record fidelity across multiple facets: adherence, quality, and child responsiveness (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Durlak, 2010; Durlak & DuPre, 2008; a copy of the checklist is available from the first author). Dose was monitored using daily logs, which was completed by the interventionists after every session. Fidelity of implementation including adherence, quality, and responsiveness is summarized for Head Start teachers and research team interventionists separately. When averaged across all observations, the research team achieved a mean fidelity of 95% (range = 83%–100%; SD = 5.6) and the Head Start teachers achieved a mean fidelity of 90% (range = 74%–100%; SD = 8.4). Using logs to monitor children’s absences and delivery of lessons, we determined that all eight research participants received an adequate dose of the intervention (i.e., at least 80% of lessons).

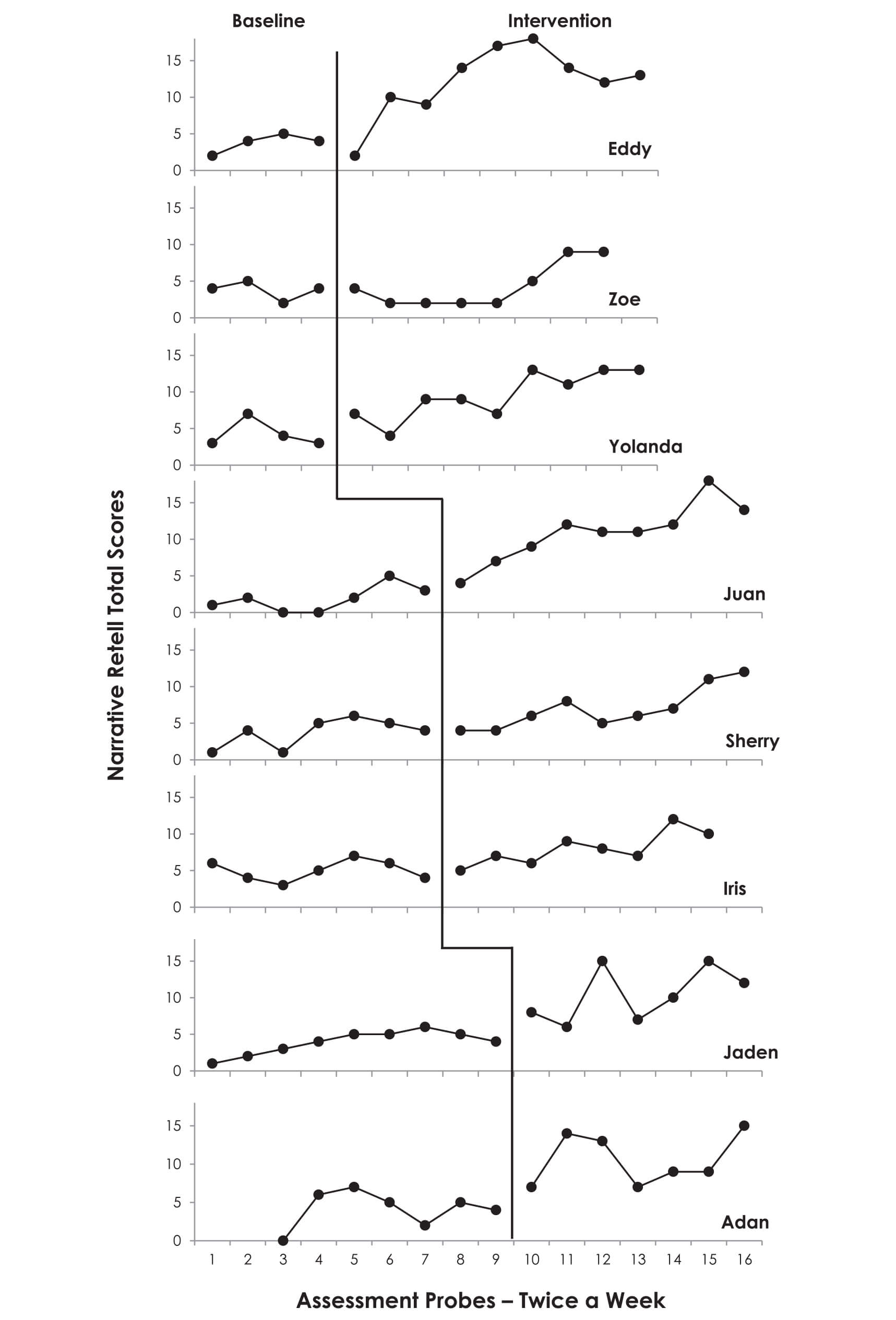

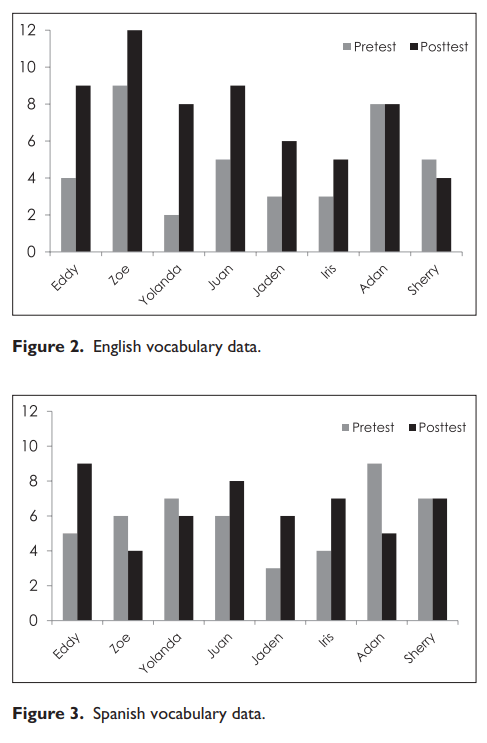

Data analysis. Children’s English retell scores were graphically displayed in a multiple-baseline design fashion spanning baseline and intervention conditions. Each child’s baseline and intervention data were analyzed according to within- and between-phase patterns of responding with respect to level, trend, variability, overlap, and immediacy of effect (Gast & Spriggs, 2014). Concerning vocabulary, each child’s pretest and post-test English and Spanish totals were graphically displayed. Also, group means and Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated for pretest and post-test English and Spanish data.

Results

The primary research question addressed growth in English retell performances related to dual-language intervention. In Figure 1, the individual children’s baseline and intervention data are displayed. All of the research participants produced short and incomplete retells during baseline. Characterized by a great deal of consistency, most children produced slightly ascending trends and mildly variable patterns with scores ranging from zero to seven during baseline. Although children in Class 1 stabilized within a few data points, several baseline sessions were necessary before data stabilized for children in Classes 2 and 3. Following the onset of small group intervention, Eddy, Yolanda, Juan, Adan, and Jaden showed clear trend changes. Once intervention began, Eddy showed a quick level change as well as a stably ascending pattern of responding. Yolanda did not experience a quick level change, but rather a slow and steady ascending trend. Juan’s intervention data also show a consistently ascending pattern. Although variable, the level of Adan’s data increased drastically within two data points. Likewise, Jaden experienced a quick level change with moderate variability. Although Zoe, Iris, and Sherry also showed improvements, they were notably less immediate than the others, especially for Zoe who did not show any improvements for several weeks. Their delayed responses resulted in at least half of their intervention data points overlapping with their baseline data points. Eddy, Juan, Jaden, and Adan achieved high scores between 15 and 18, whereas Zoe, Yolanda, Sherry, and Iris achieved high scores between 10 and 13. None of the children demonstrated a change in Spanish retells because during baseline all of the participants produced Spanish retells at their developmental level. Spanish data are available upon request.

The second research question examined the effect of the dual-language intervention on children’s acquisition of the targeted vocabulary words. For English, the group’s mean scores were 4.7 (SD = 2.4) at pretest and 7.2 (SD = 2.7) at posttest. For Spanish vocabulary, the mean score at pretest was 5.4 (SD = 2.2) and the mean score at posttest was 6.0 (SD = 2.1). Cohen’s d effect size estimate for dependent samples was used to determine the magnitude of change. Change from pretest to posttest in English represents a large effect (d = .98) whereas the change from pretest to posttest in Spanish represents a small effect (d = .34). Figures 2 and 3 show the individual pretest, post-test results. In English, all of the children except Adan and Sherry knew more words at posttest than at pretest. The average number of English words acquired was three; however, there was a great deal of variability among the children. Eddy learned five words, Yolanda learned six words, and Sherry and Adan learned none. In Spanish, Eddy, Juan, Jaden, and Iris knew more words at posttest than at pretest, but Zoe, Yolanda, Adan, and Sherry performed the same or worse on the receptive vocabulary assessment at posttest than at pretest.

Parents’ responses to the short questionnaire reflect a level of social validity. Parents reported that they engaged their child in the take-home activities most of the time, with an average rating of 4.3 on a 0 to 5 scale. Six parents reported that they used English and Spanish and two parents reported that they completed the activities in Spanish only. Parents were also asked whether they enjoyed the storytelling activities, whether their children enjoyed them, and whether their children’s language improved as a result of the take-home activities. On a scale from 0 to 5, with 5 being often and 0 being never, parents reported an average score of 4.8, 4.9, and 4.8 to those questions, respectively.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the promise of a dual language-narrative intervention with embedded vocabulary instruction for improving preschoolers’ English narrative retells and targeted vocabulary in Spanish and English. Although it was an exploratory study, we expected that children’s English retells and vocabulary knowledge would improve, but we were uncertain the extent to which the dual-language intervention would be powerful enough to impact children’s Spanish retells and vocabulary knowledge. The results indicated that the DLLs in this study improved their English narrative retells as a result of the dual-language intervention. From pretest to posttest, children’s English receptive vocabulary of the targeted words improved in English, but only a few children learned target words in Spanish. For English language outcomes, the intervention appears to have promised on English-language outcomes. Although we did not expect participants to make noticeable improvements in Spanish retelling because their baseline scores were at developmentally appropriate levels (score of eight), all children maintained their Spanish retelling performance during the intervention phase.

Narratives. The current findings are considered adequate to establish a functional relationship between the independent and dependent variables. When compared with the What Works Clearinghouse design standards, this study would be classified as “meets standards with reservations.” Had the baseline phase for Class 1 included five data points instead of four, it would have met the standards without reservations (Kratochwill et al., 2013). Based on visual analysis, we conclude that the dual-language intervention produced meaningful improvements in children’s English narrative retell skills. These findings align with previous narrative intervention results. Across multiple studies, strong effect sizes have been consistently documented for small group narrative interventions with Spanish-speaking English learners (Spencer, Petersen, & Adams, 2015; Spencer & Slocum, 2010; Weddle et al., 2016). When the focus of the intervention is divided between two languages, as was the case with the dual-language intervention used in this study, the intervention is robust enough to have a meaningful impact on DLL’s English narrative abilities. This adds to the increasing body of research that has shown that a dual-language approach does not adversely affect English language growth and development (i.e., Restrepo et al., 2013) and can facilitate the acquisition of English skills, such as story structure, sentence complexity, and concept development (Baker, 2000; Coltrane, 2003; Cummins, 2000; Gibbons, 2002; Pearson, 2002; Restrepo et al., 2013).

It is unknown whether the Spanish lessons facilitated or accelerated children’s gains in English, but other evidence seems to support an additive effect (Méndez et al., 2015; Restrepo et al., 2013). It is possible that the native language component of intervention facilitated growth in English, but given the limited scope and exploratory nature of the current study, we were unable to examine that aspect of the intervention. Nonetheless, the advantage of bilingual language development is well documented in the literature (August & Shanahan, 2006; Rolstad et al., 2005; Slavin & Cheung, 2005). Without it, many families lose their ability to communicate, and children either do not continue to develop their native language skills for academic purposes or demonstrate protracted development (Castilla-Earls et al., 2016; Morgan, Restrepo, & Auza, 2013). In the context of English-only education, these effects are expected to continue and worsen beyond preschool. In the current study with a supplemental program, children’s Spanish narrative development seemed to be up to par with developmental expectations. However, without continued Spanish language promotion, they are at risk of losing proficiency in Spanish.

Despite a general experimental effect of the dual-language narrative intervention on children’s English retelling skills, there were considerable individual differences. Some children showed quick responses and for others, the effect took longer to emerge. Evidenced by the magnitude and immediacy of change, five of the children showed strong effects while three participants showed slower and more moderate improvements. Eventually, all children retold English stories with NLM: Listening scores above an eight. This score represents a minimally complete story and is considered developmentally appropriate for preschool children. Four of the participants produced retells between scores of 15 and 18, which are exceptional for preschool children. A story earning 15 points includes a basic episode (problem, action, consequence, or ending), some enhanced components such as the setting and feelings, and usually a few language complexity elements such as because, when, and after. Young children who can reliably produce stories with this level of complexity are better prepared for academic instruction in elementary school. In fact, the higher scoring children in this study produced narratives with greater complexity than what is currently expected in kindergarten and first-grade curriculum standards (e.g., Common Core State Standards; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010).

Children’s response to intervention did not correspond to their performance on the Spanish norm-referenced language tests administered at the beginning of the study. Some children with lower Spanish language skills on the CELF-P-2 made substantial gains in English (e.g., Adan and Jaden) and some children with average Spanish language skills showed moderate gains related to the intervention (e.g., Iris and Sherry). Based on the current intervention and arrangement, we were unable to predict children’s English response to instruction based on their Spanish language skills. This limited relationship between vocabulary words during the children’s school day helped children learn the words in English. Teachers naturally used the target words in English, which provided additional practice opportunities. Because English was the primary language of instruction throughout the day, the children did not have the opportunity to listen to or use the Spanish vocabulary words to the same extent as the English words. These results contrast with those of Restrepo et al. (2013), in which gains in Spanish were documented. However, there were multiple methodological differences between the studies: Restrepo et al. (2013) targeted mostly nouns, there was explicit vocabulary instruction 4 days a week instead of 2 days a week, and they provided review lessons. It is possible that direct and indirect instruction in Spanish, as opposed to direct instruction only, may speed up the acquisition process. Marulis and Neuman (2010) reported that effective vocabulary instruction leveraged instructional time across the day, thereby increasing the number of exposures and opportunities for practice.

In classrooms where the majority of the children are English-only speakers, it may be challenging for teachers to encourage the use of Spanish vocabulary words throughout the day. Even the teacher of Class 3 whose first and most proficient language was Spanish spoke primarily English to the children throughout the school day. Therefore, the limited gains in Spanish could be the result of less time dedicated to Spanish instruction and general conversation in the classroom. Perhaps an alternative would be to promote Spanish skills at home by providing parents/caregivers with a list of words or materials to help them emphasize the words at home.

Limitations

Although the dual-language narrative intervention shows promise for improving oral language skills, we are mindful of several limitations. The first limitation is related to our inability to conduct a follow-up probe examining the extent to which the children maintained their retell improvements after a period of no instruction. We did not collect intervention fidelity data during baseline to help differentiate the conditions. Had we documented the extent to which teachers taught vocabulary and narratives during baseline, we could have more confidence in the intervention effect. The CLASS results offer some information about how well teachers modeled language in their classrooms. On a 1 to 7 scale, where 7 is high, the teachers scored relatively low (3, 2.7, and 4), suggesting that teachers did not demonstrate strong language modeling in their classroom.

Another limitation is related to our approach to measuring vocabulary acquisition. Typically, researchers select words consisting mostly of nouns and easily pictured verbs so that picture vocabulary assessments will be sensitive to intervention effects and developmentally appropriate for young children (Hoffman, Teale, & Paciga, 2013; LugoNeris et al., 2010; Restrepo et al., 2013). In our dual-language intervention lessons, we targeted adjectives and verbs that are more abstract and challenging to picture, such as brave, rough, tremble, and dangerous. Because we did not restrict our vocabulary targets based on the ease of assessment, likely, our receptive picture vocabulary assessment did not adequately measure the children’s true vocabulary growth. The portrayal of dynamic vocabulary using static pictures could have also reduced children’s ability to appropriately respond to the questions and therefore, demonstrate their vocabulary knowledge.

Future Research

There are many potentially fruitful avenues for future research stemming from the limitations and findings of this study. Considering this was an early phase study in the iterative development of a new curriculum, it lacked a handful of rigorous methodological features that can be improved in follow-up studies. For example, future research should examine the maintenance of effects following the withdrawal of the intervention, use a control group with randomization to examine vocabulary acquisition, and ensure at least five data points occur within each condition for single-case design studies. Research that examines the effect of English-only versus dual-language interventions on English-language outcomes would be a good next step in this line of research, especially given we were unable to isolate the effect of Spanish intervention component in the current study. It would be worthwhile to enhance or modify the intervention so that it is potent enough to improve Spanish vocabulary acquisition as well. In this study, parents reported that they completed many of the take-home activities with their children and they enjoyed the activities. This suggests boosting the dose and quality of Spanish language promotion via a stronger take-home component is worth exploring.

A number of improvements regarding measurement are also noteworthy. Given the limitations of the receptive vocabulary measures used in the current study, future research should include improved measures to ensure valid assessment of vocabulary growth. In general, vocabulary measurement in preschool is an area that warrants additional research because there is great value in teaching more challenging words than what can be depicted in an illustration and there are many weaknesses related to the receptive picture vocabulary methods commonly used (Hoffman et al., 2013). Likewise, it would be advantageous to have a distal measure of language to determine whether the intervention has a lasting and robust impact. For the current study, which was the first study of the dual-language narrative intervention in an abbreviated format (8 weeks), it was not likely that distal outcomes would have been impacted. If subsequent studies feature a longer and more fully developed intervention, the inclusion of distal language measures is reasonable and necessary.

Conclusion

This study reflects an initial attempt to examine the effect of a Spanish–English narrative intervention with embedded vocabulary instruction on children’s Spanish narrative retelling skills and acquisition of English and Spanish vocabulary words. Using multiple-baseline design conventions, we established a causal relationship between the dual-language intervention and the English retell outcomes; however, only a portion of the children showed clear level and trend changes. Retell improvements were delayed for three children. Although only a few children learned some of the Spanish vocabulary words, all but two children learned many of the English vocabulary words. Findings suggest the dual-language intervention has promise for promoting the English language while maintaining children’s first language. Future research is needed to improve the rigor of the evidence and to enhance the potency of the intervention.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to Northern Arizona Council of Governments Head Start and Sally House, Lupita Soto, and Rosanne Gonzales who made valuable contributions to the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305A140093 for US$1,481,960. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.