Douglas B. Petersen

University of Wyoming

Laramie, WY

Disclosure: Douglas B. Petersen has no financial or nonfinancial relationships related to the

content of this article.

Trina D. Spencer

Northern Arizona University

Flagstaff, AZ

Disclosure: Trina D. Spencer has no financial or nonfinancial relationships related to the

content of this articles.

This authors of this article present a new language assessment, the Narrative Language

Measures (NLM), designed for screening, progress monitoring, and intervention planning

purposes. The authors examine NLM for its ability to satisfy the requirements of the

assessment of language in a Response to Intervention (RTI) framework. Specifically, they

describe the extent to which the NLM reflects socially important outcomes, involves

standardized administration and scoring procedures, is time efficient and economical, has

adequate psychometric properties, and is sensitive to language growth over time.

“What any person in the world can learn, almost all persons can learn if provided with

appropriate prior and current conditions of learning.” —Benjamin Bloom (1985)

Each child deserves an education specially tailored to his or her needs, and for some

time now, education policy has been shifting in the direction of providing individualized

education to all children (e.g., No Child Left Behind Act, 2001; Individuals with Disabilities

Education [IDEA], 2004). Appropriate education for all children requires individualized

attention, where a student’s progress is carefully monitored and adjustments are made

according to his or her response to the instruction rendered. One way to address the needs of

all children is to apply a Response to Intervention (RTI) model in schools (American SpeechLanguage-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2012; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). RTI is a fairly recent

educational initiative that often features three tiers of specialized instruction. This tiered

system allows for increases in instructional intensity (from tier 1 to tier 3) based on a student’s

progress. Children are provided an intensity of instruction appropriate for their individualized

needs, and because needs are not permanent, intensity of instruction is fluid across tiers. To

guide decisions regarding the appropriate intensity of instruction, valid screening, progress

monitoring, and intervention planning practices are required components of effective RTI

systems (Greenwood et al., 2008). The purpose of this report is to introduce a new assessment

tool that can fulfill these RTI measurement functions and help extend RTI to the domain of

language.

General Outcome Measurement and Language

Determining what students should progress toward and frequently assessing their

progress is key to effective, individualized education for all students (Common Core State

Standards, 2012). In U.S. schools, a popular assessment approach is to use curriculum-based

measurement (CBM), which facilitates repeated sampling of student performance in content

that closely aligns with the school’s local curriculum (Deno, 2003). More generic CBM, often

referred to as general outcome measurement (GOM), involves sampling of student performance

in content that is not derived directly from a school’s curriculum (Fuchs & Deno, 1994), yet

reflects a generally important academic outcome. CBM and GOM methods have substantial

support as effective means of monitoring student progress and are well suited to serve in

specialized, RTI educational climates (Baker & Good, 1995; Espin & Deno, 1993, Fuchs, 2004;

Fuchs, Deno, & Mirkin, 1984; Kaminski & Good, 2010).

Deno, Mirking, and Chiang (1982) suggested that GOM assessment instruments should

(a) measure authentic child behaviors and key skill elements that represent important

outcomes, (b) have standardized administration and scoring procedures, (c) be time efficient

and economical, (d) meet the requirements of technical adequacy, and (e) be sensitive to growth

due to intervention or change over time.

Language proficiency plays a foundational role in many academic domains, particularly

in reading comprehension (Dickinson & McCabe, 2001; Dickinson, McCabe, & Essex, 2006).

Currently, there are no screening and progress monitoring tools that meet GOM requirements.

The lack of GOM instruments for language may have much to do with the contrast between

GOM requirements and the traditionally complex methods used to analyze language.

Standardized, reliable, valid, efficient, and economical assessments of language discourse have

not yet been successfully developed. There is an urgent need for such measures of language

(Ukrainetz, 2006), especially if speech-language pathologists are going to become key RTI team

members. To address this urgent need, we developed a new narrative-based language

assessment tool called the Narrative Language Measures (NLM).

The Narrative Language Measures (NLM)

The NLM is comprised of three subtests: the Test of Narrative Retell (TNR), the Test of

Story Comprehension (TSC), and the Test of Personal Generation (TPG). The TNR involves

reading a model story to a child and then asking the child to retell that story. In the TSC, an

examiner reads a story to a child and asks factual and inferential questions about the story.

The TSC may be more appropriate for younger children and children with extremely limited

language skills because it generally requires less expressive language skills than the TNR. The

TPG involves telling a model story to a child and then asking the child to tell his or her own

personal story that is thematically related. Personal narratives from the TPG subtest can be

elicited immediately after a child retells a TNR story by asking if a problem similar to the

modeled story had ever happened to him or her. TPG subtests can also be administered using a

conversation elicitation procedure (McCabe & Rollins, 1994), in which the examiner shares

three stories (one at a time during a conversation) and asks the child if something similar had

ever happened to him or her.

There are currently two developed versions of the NLM designed for use with preschool

children (NLM:P; Spencer & Petersen, 2010) and kindergarten students (NLM:K; Petersen &

Spencer, 2010); other versions (first through third grade levels) are at varying stages of

development. There are 25 short stories for each of the NLM levels, each with consistent

structure, length, and language complexity. The NLM stories highlight events that young

children are likely to experience in their daily lives (e.g., getting hurt, losing something).

Because the NLM:P is currently the most researched version, it will be the primary focus of this

report.

Requirements of a General Outcome Measure

We frame the following subsections under headings that align with GOM requirements.

Our research has not yet addressed all of the necessary characteristics of GOM, but it is

sufficient to provide preliminary evidence and to examine the NLM’s potential.

Authentic Child Behaviors and Key Skills That Represent Important Outcomes

The NLM was designed to represent the construct of narrative language. NLM stories

are based on personal narrative themes that reflect realistic situations many children have

experienced and include narrative features common in typical children’s stories. Narrative is an

authentic, socially relevant discourse that reflects general language ability (Bishop & Adams,

1992; Boudreau, 2008; Hughes, McGillivray, & Schmidek, 1997; McCabe & Marshall, 2006).

Narration is explicitly and implicitly connected to the core curriculum (Petersen, Gillam,

Spencer, & Gillam, 2010) and is associated with reading ability (Dickinson & Snow, 1987) and

academic success (Bishop & Edmundson, 1987). For younger children, personal narratives are

particularly important for social development (Johnston, 2008). Personal narratives are

common in children’s communication and are functionally important for promoting generalized

use of language (Preece, 1987). It is important for young children to be able to tell parents

about their day or report a conflict to a teacher. The ability to use and understand the complex

language used in narration signifies that a child will likely be able to use and understand the

complex language common in schools (Griffin, Hemphill, Camp, & Wolf, 2004).

Standardized Administration and Scoring Procedures

The NLM includes standard administration protocols for eliciting narrative retells,

personal stories, and story comprehension. Each subtest is scripted for consistent

administration, with detailed information on acceptable examiner prompts. The standardized

NLM scoring rubrics consists of 0–2 or 0–3 point ratings for two critical subscales—story

grammar and language complexity. This scoring format is founded on previous research by

Strong (1998); Gillam and Pearson (2004); and Petersen, Gillam, and Gillam (2008). Narrative

organization is comprised of elements often referred to as story grammar (Stein & Glenn, 1979).

Story grammar includes expected features of a story, such as the description of a setting, a

problem, attempts to solve the problem, and the consequence (Peterson, 1990; Peterson &

McCabe, 1983). When combined, these key features of a story are called episodes (plots). A

narrative, like any other type of discourse, is also built from language complexity. Language

complexity used in narration can be evaluated according to the degree to which more complex

and meaningful structures are present. A story can be told using very basic vocabulary and

grammar, but more successful narratives involve complex sentence structures with a clear time

sequence and causal connections between events. This elaborated, complex language helps add

emphasis and climactic shape to stories and is revealing of academically related language

proficiency (Labov, 1972).

With the TNR subtest, children’s retells can be scored in real time or audio recorded for

later scoring. With the TSC, examiners write children’s responses to questions, which can be

scored easily in real time, following administration, or after listening to an audio recording of

responses. Children’s personal story generations are typically scored from a transcribed

recording.

Time Efficiency and Economics

Administration for each NLM subtest takes approximately 2–5 minutes and the TNR

and TSC subtests can be scored in real time while the child is narrating. This is of critical

importance to clinicians who may not have time to record and transcribe language samples

before calculating scores. The materials necessary to administer the NLM have minimal costs,

similar to other GOM measures currently available (e.g., DIBELS; Good & Kaminski, 2010).

Technical Adequacy: Reliability

Reliability is “the extent to which individual differences in test scores are attributable to

‘true’ differences in the characteristics under consideration and the extent to which they are

attributable to chance errors” (Anastasi, 1988, p. 109). A measure is considered reliable when

it yields consistent scores over a variety of conditions (Gall, Gall, & Borg, 2007). Reliability can

be measured through self-consistent analyses or through retesting procedures. Nunnally

(1967) suggests that relatively low reliability coefficients (.5) are acceptable in early stages of

research, but that once measures are used to make important decisions regarding student

placement and treatment, reliability should be much higher. A GOM instrument should have

as little measurement error as possible. Strong internal consistency, interrater agreement, and

reliability of alternate forms are of paramount importance.

Alternate Form Reliability. Each of the stories in the NLM was thematically written in

consideration of “typical” personal events that might occur in a child’s life in the United States.

The NLM stories were leveled on multiple features including consistent story grammar;

equivalent number of words; equivalent adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, and conjunctions; and

equivalent syntactic complexity with the same number of adverbial, nominal, and relative

subordinate clauses represented in each story.

Multiple narratives collected from 71 preschool-age children with a mean age of 57.6

months (SD 3.67) were analyzed to investigate alternate form reliability and other evidences of

technical adequacy. Fifty-four percent of the preschool participants were English Language

Learners and all children were of low socioeconomic status. For additional details concerning

the participants and procedures, please refer to Spencer, Petersen, Slocum, and Allen (in

press). A random selection of NLM:P stories for all three subtests were administered to the

children six times within three weeks. The six TNR story retell results, six TSC story

comprehension results, and six TPG story generation results were analyzed for alternate form

reliability within subjects. The two-tailed bivariate Pearson correlation was .77, p < .001 for the

TNR; .88, p < .001 for the TSC; and .61, p < .01 for the TPG. In general, we found moderately

strong preliminary evidence of alternate form reliability for the subtests of the NLM, with

stronger results with the TNR and TSC.

Fidelity of Administration. A GOM instrument must have standardized procedures that

can be followed with fidelity so that multiple examiners can administer the assessment

consistently. Twenty percent of the TNR and TPG administrations and 30% of the TSC

administrations were assessed for fidelity of administration across examiners. A procedural

checklist, including items for scripted administration and neutral prompting, was used to track

percent of administration steps completed correctly. For the TNR subtest, mean fidelity of

administration was 91%. For the TPG subtest, mean fidelity of administration was 93%. For

the TSC subtest, fidelity of administration was mean 98%. The fidelity of administration for the

NLM subtests appears to be excellent, suggesting that administration is not difficult.

Interrater Reliability. Scoring narrative language can be a complex and difficult task. An

assessment of narrative language must include procedures that promote reliable scoring across

examiners. For the TNR, we investigated the interrater reliability of scoring from a transcript

and from a simulated real-time scenario. For the TSC, we investigated the interrater reliability

of scoring from transcribed responses. For the TPG, interrater reliability was investigated by

analyzing transcribed stories.

Point-by-point agreement was calculated for 20%–30% of the subtests by dividing the

number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements multiplied by 100. For

the transcribed TNR stories, a trained graduate student and the first author achieved a mean

agreement of 96%. For the transcribed TPG stories, the same independent scorers had a mean

agreement of 94%. For the TSC subtest, scoring by a trained undergraduate student and the

second author achieved a mean agreement of 91%.

For the TNR stories that were scored in real time, several trained graduate students

independently listened to an audio recording of the children’s narratives. The graduate

students were only allowed to listen to the audio recording one time, simulating a real-time

scoring context. Mean agreement for real-time scoring was 91%. When comparing real-time

TNR scores to scores derived from transcribed narratives, mean agreement was 93%. All of the

agreement scores for the NLM subtests are above a traditional acceptability level, suggesting

adequate interrater reliability.

Technical Adequacy: Validity

Validity, according to The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing

(American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National

Council on Measurement in Education, 1999) is the “degree to which evidence and theory

support the interpretation of test scores entailed by proposed uses of tests” (p. 9). As pointed

out by Gall et al. (2007) and Messick (1995), it is the interpretation of test scores that holds

validity. That is, the results of a GOM instrument need to be interpretable and meaningful, and

actions based on test results need to be appropriate (Gall et al., 2007; Messick, 1989, 1995).

Test validity can be measured by accumulating evidence to support the proposed application of

test results. When examining the validity of an assessment instrument, the content relevancy

of the measures, often referred to as content validity, represents evidential, interrelated facets

of the unitary concept of validity (Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991). The examination of test

content can include theoretical and empirical analyses along with more surface-level analyses

such as logical and expert judgment. Each of these analyses should focus on the extent that

the content of a test reflects the construct of interest.

Additional means of gathering evidence of construct validity include calculating

intercorrelations among subtests and factor analysis. Examining the relationship between the

results of a measure and the results of other measures designed to assess the same construct

can also derive evidence of validity. This examination is designed to demonstrate the extent to

which an instrument matches comparable, previously validated instruments in rank ordering

individual performances (Bachman, 1990; McNamara, 2000). This convergent-correlational

evidence of validity, often represented as criterion-related validity, is highly dependent on the

existence of valid, external tests.

Construct Validity: Intercorrelations. If the subtests of an assessment are significantly

correlated, this can be evidence that the subtests are all measuring a related construct. The

retell (TNR) and story comprehension (TSC) subtest correlation was .43 (p = .005). The TNR and

story generation (TPG) subtest correlation was .64 (p = .0001). The TPG and TSC subtests were

not significantly correlated (.23, p = .10). These correlations suggest that the retell and story

comprehension subtests are assessing a similar construct (narrative comprehension), and that

the retell and personal generation subtests are assessing a similar construct (narrative

production), but that the personal generation subtest and the story comprehension subtests

are testing different constructs.

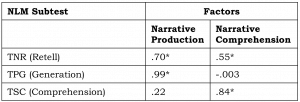

Construct Validity: Factor Analysis. Factor analysis is conducted to explore the degree to

which underlying traits of a test can be identified and the extent to which those traits reflect

the theoretical model on which the test is based. Principal components exploratory factor

analysis was conducted, followed by a maximum likelihood factor analysis. Three criteria were

used to determine the number of factors to rotate: the a priori hypothesis that the NLM

subtests measured narrative production and narrative comprehension, the scree test, and the

interpretability of the factor solution. The scree plot indicated that our initial hypothesis was

correct. Based on the plot, two factors were rotated using a Varimax rotation procedure. The

rotated solution yielded two interpretable factors, narrative production and narrative

comprehension (Table 1). Narrative production accounted for 37% of the item variance, and

narrative comprehension accounted for 32% of the item variance. The narrative production

factor included the TPG and TNR subtests. The narrative comprehension factor included the

TSC and TNR subtests. The TNR subtest loaded on both factors, just as our intercorrelation

findings indicated. This factor analysis finding suggests that each of the subtests is reflective of

different, interrelated facets of the construct of narration.

Table 1. Factor Analysis of the NLM Subtests

Note. TNR = Test of Narrative Retell; TPG = Test of Personal Generation; TSC = Test of Story

Comprehension

* p < .05

Construct Validity: Criterion-Related Evidence. To measure evidence of criterion-related

validity, we analyzed mean TNR scores administered to five preschool children. Details about

the participants and procedures can be reviewed in Spencer and Slocum (2010). We compared

mean TNR scores to The Renfrew Bus Story (Cowley & Glasgow, 1994), which is a standardized,

norm-referenced assessment of narration that has good evidence of validity. We also compared

the average TNR scores to an adapted version of the Index of Narrative Complexity (INC;

Petersen et al., 2008), which is a scoring rubric (without stories) designed for school-age

children that preceded the development of the NLM. The INC and the NLM use similar scoring

procedures and scales. The INC has good initial evidence of validity (Petersen, et al., 2008). The

TNR and Bus Story scores correlated at r = .88, and the INC and NLM scores correlated at r =

.93. Our preliminary evidence suggests that the TNR subtest assesses the same construct as

previously validated measures of narration.

Sensitivity to Growth Due to Intervention or Change Over Time

Thus far, our research with the NLM has been associated with intervention studies. We

do not yet have evidence of the NLM being sensitive to change over time due to maturation or

age. However, evidence of the NLM being sensitive to growth due to intervention is extremely

promising. In the Spencer et al. (2012) study, two classrooms of Head Start students

participated in 12 15-minute sessions of large group narrative intervention. Two comparable

classrooms of Head Start students served as a control group, and significant gains for the

treatment group were detected on the TNR and TSC subtests in a relatively short period of time

(e.g., three weeks). Spencer and Slocum (2010) conducted small group narrative intervention

with 19 Head Start students in groups of four children and one interventionist. Intervention

occurred four days a week for approximately eight weeks, and the NLM was administered prior

to daily intervention sessions. Five children served as research participants in a multiple

baseline experimental design. Substantial improvements were observed for the TNR and TPG

subtests following the onset of intervention. Some students showed immediate increases in

scores and some showed more gradual patterns of improvement. The evidence is mounting that

the NLM is sensitive to language growth due to intervention

Current Uses and Future Directions

The NLM:P was originally developed as an outcome measure for a preschool

intervention study in 2008. Aside from narrative scoring rubrics such as the Index of Narrative

Complexity (Petersen et al., 2008) and the Narrative Scoring Scheme (Miller & Chapman, 2004),

there were no valid and reliable language assessment tools with a sufficient number of

equivalent forms for repeated monitoring. Similarly, there were no language tools that did not

require labor-intensive transcription and scoring. We followed the literature on GOM and

curriculum-based measurement to design a language monitoring tool. Much of our efforts have

been focused on what we perceived to be the greatest obstacles—time efficiency and technical

adequacy. It appears that we have been able to develop an assessment tool that largely meets

the GOM characteristics, but more research is needed. As a result of the NLM’s promise,

additional grade-level measures are in the development process and research efforts have

expanded. The NLM:P and NLM:K have recently been employed as outcome measures in seven

recent intervention studies (Brandel, Spencer, & Petersen, 2012; Kajian, Bilyk, Marum, &

Spencer, 2012; Petersen, Brown, De George, Zebre, & Spencer, 2011; Smith, Spencer, &

Petersen, 2011; Spencer, Kajian, Bilyk, & Petersen, 2012; Thompsen, Petersen, & Spencer,

2012; Tonn, Petersen, & Spencer, 2012) and were the focus of investigation in at least two

others (Chanthongthip, Petersen, & Spencer, 2012; Tilstra, Petersen, & Spencer, 2012).

Our preliminary data from research are encouraging; however, a true test of usability

comes from clinicians. Other language professionals and educators have expressed enthusiasm

about the potential of monitoring language over time using a standardized measure that has

multiple equivalent forms. We have, and continue to provide, support to school districts and

clinicians who pilot the tools in applied settings so that we can learn from them. This has been

highly valuable, because clinicians have shared with us what they need and provided specific

suggestions for improvement. Based on reports from clinicians, the NLM likely has many uses

in schools. First, because the TNR is intended to be a GOM tool, it can be used to screen

children for language needs, much like how measures of reading fluency are used in schools.

Although the TSC and TPG necessitate lengthier scoring procedures, they can also be used for

screening. Sometimes, it is helpful to use all three subtests to ensure a comprehensive picture

of a child’s language production and comprehension abilities. A second purpose is progress

monitoring. The 25 alternate forms allow for frequent repeated probing of the same skills over

time. Using the NLM subtests, children’s language could be sampled quarterly, monthly, or

weekly, depending on the intensity of language instruction and intervention. Clinicians may

select subtests for progress monitoring according to the needs and language targets of

individual children. Third, results from the NLM subtests can be used to identify language

targets and inform intervention. For example, story grammar can be addressed with children

who fail to produce a complete episode. Morphosyntax, vocabulary, and comprehension of

factual and inferential questions can also be identified as worthy intervention targets through

the use of the NLM. Careful examination of TPG results can help identify clinical targets,

inform intervention planning, and provide a sample of a child’s generalized independent

narrative ability.

Although the NLM can be used for these purposes, there are a number of limitations of

employing measurement tools that are not fully developed, validated, and disseminated. Often,

clinicians inquire why other features that seem relevant to language measurement are not

scored in the NLM. This is an important question because the answer is critical for

understanding what the NLM is and what the NLM is not. GOM is not intended to be detailed

measurement of the construct of interest. Rather, GOM tools are proxy measures that estimate

a socially important domain. In this case, the NLM reflects general language ability that is

academically relevant. Due to the other characteristics of GOM (e.g., time efficiency), there are

trade-offs in the inclusion of features that are able to be scored. For that reason, the scored

features of the NLM are restricted to those that are closely related to general language ability.

By selecting some features and not others, we compromise some important aspects so that it

can be used by professionals without extensive knowledge of language and be scored efficiently

and reliably. This could be perceived as a limitation of the NLM. For language experts who want

more detailed information, we encourage them to record narrative productions from the NLM,

transcribe them, and analyze the transcripts as one might do with a traditional language

sample. The advantage of using the NLM stories as opposed to other types of stories is that the

NLM stories can be scored quickly, have preliminary evidence of equivalency, and can provide a

more accurate picture of growth than stories that are variable.

Currently, the subtests do not have norms or cut scores to help identify children who

are at risk during the screening process. Although we are working toward this aim, in the

meantime, we encourage practitioners to establish local norms or compare narrative

productions to developmental sequences prevalent in the narrative language literature. This

type of criterion could be used as an estimate of comparison, at least until normative data can

be gathered.

Another limitation is that children, especially young children, are not accustomed to

taking tests. To make important decisions, a single administration of any subtest should be

avoided. We recommend that if the NLM is used for infrequent probing (e.g., fall, winter,

spring), then three TNRs, TSCs, or TPGs should be administered to increase the likelihood of

obtaining valid language performance. This is important for a number of reasons. First, the

content of the stories have some unavoidable variability. Although we have gone to great

lengths to write stories on topics that are likely to be experienced by children, there is no

guarantee that every child has experienced the featured problem. Second, children are rarely

consistent listeners and speakers. Language production and comprehension, especially in the

NLM tasks, are related to attention, memory, and cognition. The conditions of assessment and

rapport may heavily impact the results of language tests like these. The administration of three

stories in one session reduces some of the potential confounds associated with this format for

language assessment. If frequent probing is conducted, the issues of relatability of content and

attention, memory, and cognition are less critical because data are analyzed for trend, not

level. However, we recommend one or two practice tests so that children can become familiar

with the expectations of the tasks.

Given that narration is an advanced language skill, many young children are unable to

produce narratives without additional assistance. Many clinicians ask whether we plan to use

pictures with our retell tasks. Picture supports are common in narrative tests; however, we

have aimed to develop an authentic test that reflects general language ability. The language a

child produces is natural contexts is often substantially different than language produced

when prompted by visual cues. Children most often tell personal stories about events they have

directly experienced or observed, and picture cues are rarely available in spontaneous, natural

storytelling exchanges. For that reason, we strive to reduce the extraneous supports in our

measurement context and make the tasks as authentic as possible (e.g., relatable content,

auditory/oral) while still adhering to the characteristics of GOM. That being said, we recognize

that some children with significant language limitations or very young children are unable to

produce even the most basic narrative retell. Without using additional supports, we can

artificially create floor effects, whereby many children score zeros.

In a pilot study of the effects of TNR administered with and without pictures, we found

that preschoolers who produced a quality retell with pictures were able to produce a quality

retell without pictures, too. Some children who were unable to produce a retell without pictures

were able to perform better when pictures were available, although these children did not

typically produce retells with high scores. The remaining children, likely those with significant

language needs, scored zeros whether or not the pictures were available. We conclude that for a

small portion of preschoolers, or for children with significant language impairment, pictures

can help obtain a sample of children’s language. However, adequate performance on the TNR

with picture support should not be the end goal but rather an intermediate step. For children

who are 3 years old, extremely shy, or whose language is significantly limited, we recommend

pictures be used initially for testing but faded as children’s confidence and skills develop. The

newly revised NLM:P allows this option.

The future of the NLM is promising. The NLM offers hope for greater speech-language

pathologist contribution in RTI systems and differentiated intervention for young children with

diverse language needs. A GOM instrument for language has the potential to bridge a gap

between educators and language professionals by promoting the monitoring of a shared

socially and academically relevant domain. Despite the potential, there is much to be done.

Validity studies with larger numbers of participants need to be conducted, norms need to be

established, and training materials need to be refined. Thus far, the NLM development has

resulted from amazing collaboration across disciplines and between researchers and

practitioners. We wish to continue along this path and invite others to join us.

References

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council

on Measurement in Education. (1999). The standards for educational and psychological testing.

Washington, DC: AERA Publications Sales.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2012). Responsiveness to Intervention (RTI). Retrieved

from www.asha.org/slp/schools/prof-consult/RtoI.htm

Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological testing. New York, NY: MacMillan.

Bachman, L. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, UK: University Press.

Baker, S. K., & Good, R. H. (1995). Curriculum-based measurement of English reading with bilingual

Hispanic students: A validation study with second-grade students. School Psychology Review, 24, 561–

578.

Bishop, D. V. M., & Adams, C. (1992). Comprehension problems in children with specific language

impairment: Literal and inferential meaning. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 35, 119–129.

Bishop, D. V. M., & Edmundson, A. (1987). Language-impaired 4-year-olds: Distinguishing transient from

persistent impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 52, 156–173.

Bloom, B. (1985). Developing talent in young people. New York, NY: Ballentine.

Boudreau, D. (2008). Narrative abilities: Advances in research and implications for clinical practice.

Topics in Language Disorders, 28, 99–114.

Brandel, J., Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2012). Response to intervention: Early evidence of a multitiered language intervention. Manuscript in preparation.

Chanthongthip, H., Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012). Required intensity of dynamic assessment of

narratives for accurate classification of bilingual students with language impairment. Manuscript in

preparation.

Common Core State Standards. (2012). Common Core State Standards Initiative [Home page]. Retrieved

from www.corestandards.org/

Cowley, J., & Glasgow, C. (1994). The Renfrew bus story. Centreville, DE: The Centreville School.

Deno, S. L. (2003). Developments in curriculum-based measurement. The Journal of Special Education,

37, 184–192.

Deno, S. L., Mirkin, P. K., & Chiang, B. (1982). Identifying valid measures of reading. Exceptional

Children, 49(1), 36–45.

Dickinson, D. K., & McCabe, A. (2001). Bringing it all together: The multiple origins, skills, and

environmental supports of early literacy. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 16, 186–202.

Dickinson, D. K., McCabe, A., & Essex, M. J. (2006). A window of opportunity we must open to all: The

case for preschool with high-quality support for language and literacy. In D. K. Dickinson & S. B. Neuman

(Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 2, pp. 11–28). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Dickinson, D. K., & Snow, C. E. (1987). Interrelationships among prereading and oral-language skills in

kindergartners from two social classes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2, 1–25.

Espin, C. A., & Deno, S. L. (1993). Performance in reading from content-area textas an indicator of

achievement. Remedial and Special Education, 14(6), 47–59.

Fuchs, L. S. (2004). The past, present, and future of curriculum-based measurement research. School

Psychology Review, 33, 188–193.

Fuchs, L. S., & Deno, S. L. (1994). Must instructionally useful performance assessment be based in the

curriculum? Exceptional Children, 61(1), 15–24.

Fuchs, L. S., Deno, S. L., & Mirkin, P. (1984). Effects of frequent curriculum-based measurement and

evaluation on pedagogy, student achievement, and student awareness of learning. American Educational

Research Journal, 21, 449–460.

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it?

Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93–99.

Gall, M., Gall, J., & Borg, W. (2007). Educational research: An introduction. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Gillam, R. B., & Pearson, N. A. (2004). Test of Narrative Language. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Good, R. H., & Kaminski, R. A. (Eds.). (2010). Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills Next (7th

ed.). Eugene, OR: Dynamic Measurement Group, Inc.

Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., Baggett, K., Buzhardt, J., Walker, D., & Terry, B. (2008). Best practices

integrating progress monitoring and response-to-intervention concepts into early childhood. In A.

Thomas, J. Grimes, & J. Gruba (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology (5th ed., pp. 535–548).

Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychology.

Griffin, T. M., Hemphill, L., Camp, L., & Wolf, D. P. (2004). Oral discourse in the preschool years and later

literacy skills. First Language, 24, 123–147.

Hughes, D., McGillivray, L., & Schmidek, M. (1997). Guide to narrative language: Procedures for

assessment. Eau Claire, WI: Thinking Publications.

Individuals with Disabilities Education (IDEA) Act, 20 U.S.C.A. §1400 et seq, 2004.

Johnston, J. R. (2008). Narratives twenty-five years later. Topics in Language Disorders, 28, 93–98.

Kajian, M., Bilyk, N., Marum, K., & Spencer, T. D. (2012, May). Teaching intraverbals, delayed tacts, and

autoclitics through narrative intervention. Poster presented at Annual Convention of the Association for

Behavior Analysis International, Seattle, WA.

Kaminski, R., & Good, R. (2010). What are DIBELS? Retrieved from www.dibels.org/dibels.html

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

McCabe, P. C., & Marshall, D. J. (2006). Measuring the social competence of preschool children with

specific language impairment: Correspondence among informant ratings and behavioral observations.

Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26, 234–246.

McCabe, A., & Rollins, P. R. (1994). Assessment of preschool narrative skills. American Journal of SpeechLanguage Pathology, 3, 45–56.

McNamara, T. (2000). Language testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13–103). New York,

NY: Macmillan.

Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses

and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. American Psychologist, 50(9), 741–749.

Miller, J. F., & Chapman, R. S. (2004). Systematic analysis of language transcripts (Version 8.0)

[Computer software]. Madison: Language Analysis Laboratory, Waisman Center, University of WisconsinMadison.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, 20 U.S.C.A. § 6301 et seq. 2003.

Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1991). Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Petersen, D. B., Brown, C., De George, C., Zebre, J., & Spencer, T. D. (2011, May). The effects of narrative

intervention on the language skills of children with autism. In T. D. Spencer (chair), Oral and written

language interventions: Typical children, at risk preschoolers, and children with autism. Symposium

conducted at the meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, Denver, CO.

Petersen, D. B., Gillam, S. L., & Gillam, R. B. (2008). Emerging procedures in narrative assessment: The

Index of Narrative Complexity. Topics in Language Disorders, 28, 115–130.

Petersen, D., Gillam, S., Spencer, T., & Gillam, R. (2010). Narrative intervention for children with

neurologically based speech and language disorders: An early stage study. Journal of Speech, Language,

and Hearing Research, 53, 961–981.

Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2010). Narrative Language Measures: Kindergarten. Retrieved from

Peterson, C. (1990). The who, when, and where of early narratives. Journal of Child Language, 17, 433–

455.

Peterson, C., & McCabe, A. (1983). Developmental psycholinguistics: Three ways of looking at a child’s

narrative. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Preece, A. (1987). The range of narrative forms conversationally produced by young children. Journal of

Child Language, 14, 353–373.

Smith, H., Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2011, May). Effects of oral language instruction on story

writing. In T. D. Spencer (chair), Oral and written language interventions: Typical children, at risk

preschoolers, and children with autism. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the Association for

Behavior Analysis International, Denver, CO.

Spencer, T. D., Kajain, M., Bilyk, N., & Petersen, D. B. (2012). Multi-tiered narrative intervention with at

risk preschoolers: Potential of RTI in Head Start. Manuscript in preparation.

Spencer, T. D., & Petersen, D. B. (2010). Narrative language measures: Preschool. Retrieved from

www.languagedynamicsgroup.com

Spencer, T. D., Petersen, D. B., Slocum, T. A., & Allen, M. M. (in press). Large group narrative

intervention in Head Start preschools: Implications for response to intervention. Journal of Early

Childhood Research.

Spencer, T. D., & Slocum, T. A. (2010). The effect of a narrative intervention on story retelling and

personal story generation skills of preschoolers with risk factors and narrative language delays. Journal of

Early Intervention, 32(3), 178–199.

Stein, N. L., & Glenn, C. (1979). An analysis of story comprehension in elementary school children. In R.

O. Freedle (Ed.), New directions in discourse processing (pp. 53-120). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Strong, C. J. (1998). The strong narrative assessment procedure. Eau Claire, WI: Thinking Publications.

Thompsen, B., Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012). Cross-linguistic transfer of complex syntax and

narrative schema. Manuscript in preparation.

Tilstra, J., Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012). Language progress monitoring using narratives: Early

clinical and technical findings. Manuscript in preparation.

Tonn, P., Petersen, D. B., & Spencer, T. D. (2012). Dynamic assessment of word learning through

inference. Manuscript in preparation.

Ukrainetz, T. A. (2006). EPB, RTI, and the implications for SLPS: Commentary on L. M. Justice.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 298–303.